Ted had been so pleased when she showed it to him that he’d insisted on taking them out for ice cream and posting her test on his fridge.

“Okay, that explains why you refused Kyle,” he said. “What about Riley?”

“He told you he called me, too?”

“He mentioned it in passing.” He turned to glance at her. “He also mentioned that you said you had to work. He thought I was being an ogre.”

“He wanted to go to the Victorian Christmas Celebration tonight.”

“And you didn’t?”

“It’s not that, it’s just...it makes no sense to ask me to something so...public. Why would anyone want to be seen with me?”

“I’m sure he knew your situation before he asked, Sophia.”

“He only understands part of my situation.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“He doesn’t know about my drinking problem. And I don’t want to tell him. I’d rather your friends think highly of me—well, as highly as they can, considering that most of my shortcomings are common knowledge.”

“You’re saying you’re not going to date anybody?”

“Not in Whiskey Creek.”

“Other alcoholics date and marry.”

“I wouldn’t risk letting someone fall in love with me if they didn’t know, and what’s the point of telling if I’ll be leaving soon?” Even if she wasn’t planning to leave, she wouldn’t date the guys Ted hung out with. She found Riley more handsome than Kyle, but she knew there were women who’d claim the opposite. Handsome didn’t matter. And it didn’t matter that they were nice. A relationship with either one wouldn’t end well, because she was in love with someone else. That was the mistake she’d made when she’d gone out with Skip—she’d gotten involved with a man who, in her mind and in her heart, couldn’t compare to Ted.

She’d been trapped for nearly fourteen years thanks to that poor choice.

“All you do is hang around the house when you’re off,” he said. “You might want to get out and have some fun once in a while.”

“It wouldn’t be fair to waste their time or money.” She’d been so engrossed in the conversation that she hadn’t been paying attention to where they were going. When Ted had exited the freeway, she assumed he was heading to Fulton Avenue and all the car dealerships along that street. But this didn’t look like...

Wait a minute! They were right by the hospital where her mother was institutionalized....

“Where are we going?” she asked.

At the alarm in her voice, he said, “It’s okay. I thought we could stop by and check on your mother, maybe drop off a little gift. And if you’re feeling up to it, we can visit her for a few minutes. But only if you’re feeling up to it.”

Sophia’s heart began to pound. It was difficult to come here, to see her mother in this setting. Elaine was so far from the woman she’d once been. To make matters worse, Sophia feared the same type of mental illness could overtake her and she’d be facing a similar future. The memories of how disjointed and upsetting their conversation on Thanksgiving had been made her anxiety that much more intense.

But when she looked at Ted, he said, “I’ll be right there beside you,” and somehow that gave her the courage to buy a poinsettia and some chocolates and carry them through those doors.

The visit with Sophia’s mother proved every bit as painful as Ted had feared. While they were there, she had almost no lucid moments. She didn’t seem to care that she had visitors, probably because she didn’t recognize them. She rambled incessantly about all kinds of things, including her underwear, which embarrassed Sophia and filled Ted’s mind with images he didn’t want to see. She tried to eat the poinsettia and ignored the chocolates, despite the fact that she was obsessed with the vending machine, specifically the candy bars it held. Sophia kept giving her dollar bills so she could slide them into the “magic slot,” as she called it. She ate four of the same kind of candy bar inside twenty minutes.

Before long, Ted was kicking himself for bringing Sophia to the hospital. When the idea first occurred to him, he’d been hoping for one special moment, one glimmer of reassurance or love from mother to daughter. He knew what it would mean to a woman who’d lost as much as Sophia. But now he thought they’d to have to leave without that—especially as Elaine’s behavior became increasingly erratic and the nurses checked in every few minutes, as if they were concerned about where it might lead.

“She can become violent,” one gently warned. “It doesn’t happen often, but you should be prepared.”

When Sophia had to use the restroom and left Ted alone with Elaine, he couldn’t quit squirming in his seat. He’d assumed he could handle this, that his calm would help Sophia cope. But he was pretty sure he found Elaine’s condition as upsetting as Sophia did. He tried to talk to her, to tell her what Skip had done and how badly her daughter needed some kind word, but she wasn’t paying attention. She kept rocking back and forth and babbling nonsense. Then she got up, returned to the vending machine and started shaking it.

She seemed to forget he was even there, but he cleared his throat, reminding her, and she came back to the table.

“Money!” she demanded.

Ted didn’t mind giving her a few bucks, but he worried about letting her eat so much candy at one time. He was afraid it would make her sick. What if she discovered that the chocolates they’d brought were just as delicious as the candy she was getting out of that machine? She’d eat the whole pound on top of what she’d already had.

“Tell you what,” he said. “If, when Sophia comes back, you’ll give her a hug and tell her you love her, I’ll leave enough money that you can buy a treat every day for a long time.”

“Money!” she demanded, as if he hadn’t just stated his terms.

“Did you hear me?” he said. “Will you do it? I know you can do it.” He actually didn’t know that, but he was hoping to encourage her. Of all the things he could give Sophia, for Christmas or otherwise, he thought this would mean the most.

Her dark eyes studied him as if he was a creature she’d never encountered before. “Who are you?”

“Ted Dixon.”

“Are you here to kill me?” she asked.

“Definitely not.”

“You look mean.”

“Sorry about that.”

“Why are you here?”

“I came with your daughter. We used to date. You don’t remember?”

“I don’t have a daughter,” she said as if she was tired of hearing otherwise and didn’t want one, regardless.

He had to wonder if she’d convinced herself that Sophia didn’t exist because it eased the pain of those moments when she came back to “herself” and remembered everything she’d lost. Or if she really believed, consistently, that she was childless. Maybe it would be just as difficult for Sophia, possibly more difficult, if Elaine remembered and begged to be released from the facility. He winced when he considered how helpless he’d feel if it was his mother in here.

“You do,” he insisted. “Her name is Sophia.”

“I like that name,” she said.

The door opened as Sophia returned, and he shoved the See’s Candies toward Elaine to distract her. He didn’t want her to say anything else about not having a daughter—or that she liked Sophia’s name as if she’d never heard it before. “Maybe you’d enjoy one of these.”

She knocked the box aside—almost onto the floor—and cast a longing glance at the vending machine. That was when Ted decided it was time to give up. He’d done what he could. This was heartbreaking to watch; he couldn’t imagine what it was doing to Sophia. He’d meant to help, but he was afraid he’d done the opposite. He hoped it wouldn’t send her back into a tailspin.

“We’d better get going or we’ll run out of time to find you a car,” he told her.

He was planning to take her to an AA meeting before they went home, but when he put a hand at her back to propel her from the room, her mother stood up and said, “Don’t go!”

The panic in her voice took them both by surprise.

“Mom?” Sophia’s eyes were wide and wary.

Nervous as to how Elaine might answer, Ted caught and held his breath. He held on to Sophia, too.

“I love you,” Elaine said, then she looked to him for approval. It wasn’t a perfect rendition of what he’d requested. There’d been less emotion in “I love you” than there’d been in “Don’t go,” and no hug, but Ted guessed Sophia hadn’t heard those three words from her mother in a long, long time.

“I love you, too,” she whispered.

Fortunately, the moment Sophia choked up, Elaine seemed to understand that the correct reaction to tears would be tenderness. Her expression softened and a vague smile claimed her lips. It was just normal-looking enough to encourage Sophia to step forward and embrace her.

Elaine didn’t do much to respond, but she didn’t try to break Sophia’s hold, either. She seemed confused.

Taking Sophia’s hand, Ted led her out of the room, and he was glad he had. As they left, he could hear Elaine yelling for money, but Sophia was so overcome with what’d just happened that she didn’t seem to put two and two together. He walked her to the car before saying he thought he’d dropped his keys and headed back.

Elaine was so upset, the nurses were having to restrain her, but the second he walked back in and held up the money he’d promised, she calmed down.

“Thank you,” he told her and put the hundred in her hand. “See that she gets a candy bar of her choosing every day for as long as this lasts, okay? And let her get it out of the vending machine herself.”

“It’ll rot her teeth,” one of the nurses said, but what else did she have to enjoy in life?

“She earned it,” he said. “Merry Christmas, Elaine. You did a wonderful thing a second ago. I appreciate it.”

“I love you,” she shouted after him as if that might bring more money, and he had to chuckle.

29

Sophia didn’t think she’d ever had a better afternoon. It was cold outside and rainy, but the car dealerships were decorated with garlands and ornaments and there was Christmas music playing every time they ducked in out of the wet. More than once they had a salesman bring them hot chocolate or hot cider. They weren’t having much luck finding a car she could afford, but just being with Ted made Sophia happy. They talked and laughed as they explored various possibilities and, during quiet moments when Ted was in discussion with a salesman or hurrying across the lot to see if the car he’d spotted in the distance might be worth investigating, Sophia reflected on what it had been like to hug her mother after so long.

Good, she decided, a miracle for the brokenhearted. She wasn’t sure she could maintain the confidence she was suddenly experiencing, but it was so wonderful to feel even remotely capable of becoming what she wanted to be that she couldn’t stop smiling. Ted seemed to like that; at one point he caught her hand and pulled her close to him as if he’d kiss her. He didn’t, but he stared down at her and said, “You are so beautiful.”

A salesman interrupted before either of them could say anything else, but she tucked that memory away, too, to savor like the warmth of the sun finally hitting her face after a long, cold winter.

She was just going over it again, wondering what he might’ve said or done next, when he nudged her. “What do you think?”

They were looking at a 2002 Hyundai Elantra with 139,000 miles for $4,500. It was silver and not bad-looking on the outside, but the inside was pretty worn.

The reality of her impoverished circumstances really sank in as she got behind the wheel and smelled the mildew the air freshener couldn’t quite conceal. Was the engine in any better shape?

She had no way to tell, and Ted wasn’t much of a mechanic.

“I’m worried it might need repairs,” she told him. “It has so many miles. But...maybe it would last a year or so.”

The salesman reassured her it was in great shape, but Sophia knew better than to trust him.

“Should we go home and think about it?” she asked.

“I doubt you’ll find anything better,” Ted replied, and that convinced her to give it a shot. This was the best option they’d come across. But when they went in to the office to see if she could get financed, they received bad news. Despite the ad Sophia had heard claiming this dealership could help anyone, the manager told her she hadn’t held a job long enough to compensate for her bad credit. Before they gave up, Ted had offered to lend her the money, but she’d refused. He’d done enough for her already.

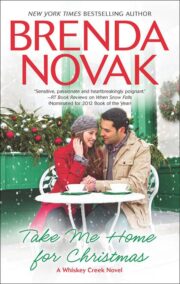

"Take Me Home for Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Take Me Home for Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Take Me Home for Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.