"You're a pretty girl," he said. "My uncle told me your daddy been keepin' you hidden away." He flashed that small smile again.

"No one's keeping me hidden away," I said sharply. He laughed.

"Why ain'tcha got a steady boyfriend then?"

"I did have," I lied, "but he had to go into the army."

"Oh?" His smile evaporated. "Uncle Jed didn't say anything about that."

"Not everyone knows. He writes me a letter every day." "Where's he at?"

"I don't know. It's a secret."

He gazed at me suspiciously and drank some more of his beer. Then he smiled with confidence again, as if he had concluded I was making it all up.

"If I get up and get me another beer, will you still be here when I get back?" he asked.

"I haven't finished eating yet," I replied, which satisfied him.

I was nearly finished by the time he returned. He had brought me a glass of beer, too.

"Just in case you change your mind," he said.

"I don't like beer."

"Oh? Whatcha like, wine?"

"Sometimes."

He nodded. "You look like a girl who has rich tastes. Betcha that's why you're still not married, huh? You're waiting for a rich catch?"

"No. Money has nothing to do with it."

He laughed, skeptically. I felt sparks of anger catch in my chest and send a heat through my body.

"I'd like to return to the dance hall," I said, rising.

"Okay. I ain't the best dancer in the world, but I'm as good as most."

I froze for a moment. I hadn't meant I wanted to dance with him, but he obviously had taken it that way.

"You wanna dance, don'tcha?"

"Okay," I said. My tongue was so reluctant to form the word, I almost choked, but I got up and went on the dance floor with him. When I looked over toward Daddy and Jed Atkins, I saw them grinning from ear to ear. Mama, who was standing with some of her friends nearby, glared in their direction, the sparks flying out of her eyes. Daddy ignored her.

The truth was, Virgil wasn't a bad dancer, and I did enjoy the music. He took it as a sign I was comfortable with him and liked him.

"I play a mean washboard," he shouted into my ear, and laughed. "Me and some friends get together at the garage and fool around. We played for a fais dodo once."

"That's nice," I said. The music got louder and faster. Virgil started to sweat profusely. He unbuttoned his shirt and gulped some more beer.

"Let's get some air," he cried finally. I was going to excuse myself and join Mama, but she was into a heavy conversation with two of her friends and had her back to me, and I couldn't think of a good excuse. "Come on, let's have a smoke."

"I don't smoke," I said.

"So you'll watch me." He took my hand and I went out with him, looking back once to see Jed Atkins pat Daddy on the back and the two of them toast each other.

We went out the rear door into the parking lot. Virgil dug a pack of cigarettes out of his top pocket and pounded one out. He lit it quickly and threw the match into the air, laughing.

"Bombs away. So you like living here?"

"Yes," I said.

"I got my car right here. Wanna see it? I souped up the engine myself." He pointed to a customized automobile with a lightning streak painted in yellow across the driver's side. "It's a drag car, you know."

"I don't know much about cars."

"Whatcha think of it?"

"It's nice," I said with thick indifference.

"Nice? It's more than nice. It's a prizewinning vehicle. You know, I won five hundred dollars in races already this year?"

"I'm very happy for you," I said. "I think we better go back inside." I started to turn toward the door when he reached out to seize my wrist.

"You're very happy for me? Boy, you're sure stuck on yourself, ain'tcha?"

"I am not."

"You sound like you are." He flipped his cigarette into the air and it bounced over the parking lot, sparks flying every which way. He still held my wrist. "Whatcha want to hurry back inside for? Just a lot of old people and kids. Come on, I'll take you for a spin in my car."

"No, thank you."

"No, thank you," he mimicked, laughed, and then he put his left arm around my waist and drew me to him before I could resist. He pasted his lips to mine with a wet kiss as his hand fell to my buttocks and squeezed. I struggled to free myself, but he held on tighter, pressing his tongue into my mouth with such force, I couldn't even block it with my teeth. I gagged and finally broke free, wiping my lips with the back of my hand.

"How dare you do that?"

"What's the big deal? You've been kissed before, ain'tcha?"

"Not like that and not without my wanting to be kissed."

He laughed. "Don't put on airs. I know all about you, how you was pregnant with someone else's baby," he added. I felt the breath leave my body and my blood drain down to my feet. "It's all right. I don't care about it. I still like you. The truth is, I learned it's better to have a woman already broke in. Learned that in the army. We'll go for a ride and get to know each other and maybe we'll get hitched. Come on," he urged, stepping toward his car.

"I wouldn't go with you if you were the last man on earth," I said.

He laughed. "For you, I might just be. Once everyone knows about you, no one's going to come around asking you to marry him. You wanna be livin' with your ma and pa till they got no teeth? I can make you happy. Better than that other man did," he added with a leering smile.

"You're disgusting," I said, and pivoted.

"Last chance," he called, "to have a real man."

I didn't reply. I couldn't get away from him fast enough. When I stepped back into the dance hall, I looked desperately for Mama and spotted her talking to Evelyn Thibodeau's mother. She took one look at me and excused herself quickly to walk across the hall.

"Gabrielle?" she said. "What's wrong, honey?"

Tears were streaming down my cheeks. "Oh, Mama," I said, "he told. Daddy told about me so that boy thought he was doing me a favor to ask me to become his wife."

She straightened as if her spine had turned to steel. When she looked for Daddy, she found he was already well on his way to a good drunk, all his buddies around him, laughing and guzzling beer and whiskey as fast as they could. She and I stood behind him. He stopped laughing and looked around fearfully for a moment.

"We're going home, Jack," she said. "Now!"

"Now? But . . . I'm jus . . . havin' some fun."

"Now," she said again.

He grew angry. "I ain't running home," he replied, "to hear you roll out complaints."

"Suit yourself," Mama said. She took my hand and we marched to the front door. "We'll walk home," she told me. "It won't be the first time I left him behind and I know it won't be the last."

10

Failing

Mama wouldn't speak to Daddy for days after the fais dodo. He didn't come home that night anyway, and when he appeared the next afternoon, looking as if he had slept in a ditch, she refused to give him anything to eat. She even avoided looking at him. He moaned and complained and acted as if he were the one who had been violated and betrayed. He fell asleep on the floor in the living room and snored so loud the shack rumbled. He woke with a jerk, his long body shuddering as if electricity had been sent through him. His eyes snapped open to see Mama hovering over him like a turkey buzzard, her small fists pressed against her ribs.

"How could you go and do that, Jack? How could you run down your own daughter for an Atkins, huh?"

He sat up and combed his fingers through his hair, gazing around as if he didn't know where he was and couldn't hear Mama screaming at him.

"We put Gabrielle through all that horror living in that dreadful woman's house secretly just so no one would know what a terrible thing had happened to her, and you go and spill your guts out to the likes of Jed Atkins? Why? Tell me that, huh?"

Daddy licked his dry lips, closed his eyes, and swayed. He lay back against the settee for a moment, making no attempt to respond or defend himself.

"And then you go and promise your daughter to a no-account slob, no better than the vermin living in the rotted shrimp boats. Where's your conscience, Jack Landry?"

"Aaaa," he finally cried, putting his hands over his ears. Mama paused, put she continued to stand over him, her little frame intimidating as she glared down at him. He took his hands from his ears slowly.

"I just done what I thought would be good for everyone, woman. I ain't no traiteur with spiritual powers like you. I don't read the future like you, no."

"Oh? You don't read the future like me? Well, it ain't hard to read your future, Jack Landry. Just go follow a snake. How it lives and how it ends up is about the same as you will," she said.

Daddy waved his hand in the air between them the way he would swat at flies. "Never mind all this. Where's that stuff you made for headaches and bad stomach trouble?"

"I'm all out of it. You get drunk so much and so often, I can't keep tip with the demand anyway," she scolded. "Besides, there's no traiteur alive who can concoct a remedy for what ails you, Jack Landry."

Whatever blood was left drained from Daddy's face. His bloodshot eyes shifted my way and then back to glance at Mama.

"I ain't staying here and be abused," he threatened.

"That's 'cause you're the one who's been doing the abusing, not us."

"That did it," he said, struggling to stand. "I'm going to go move in with Jed until you apologize."

"When it snows in July," Mama retorted, her eyes turned crystal-hard.

Daddy kicked a chair and then marched out of the house, slamming the screen door behind him. He wobbled down the steps and tripped on his own feet before making it to the pickup. Mama watched him struggle to get into his truck, gun the engine, grind the gears, and then spit up dirt as he spun the vehicle around and shot off.

"Every time I get to feeling too good for my shoes, I'm reminded how stupid I've been," she muttered. Despair washed the color from her face as she sighed deeply.

"Oh, Mama, this is all my fault," I moaned.

"Your fault? How can any of this be your fault, honey? You didn't go and pick who'd be your daddy, did you?"

"If I cared more about being married, Daddy wouldn't do these things," I wailed. I flopped into a chair, my stomach feeling like a hollowed-out cave.

"Believe me, child. He would do these things anyway, your being married or no. Ain't no rock around that Jack Landry can't crawl out from under," she said. "Pay him no mind. He'll come to his senses and come crawling back, just like he always does." She gazed after him one more time and then went back to work.

But days passed and Daddy didn't return. Mama and I worked and sold our linens, our towels and baskets. In the evenings after dinner, we sat on the galerie and Mama talked about her youth and her mama and papa, whom I had never seen. Sad times always made her nostalgic. We listened to the owls' mournful cries and spotted an occasional night heron. Sometimes there was an automobile going by, and that would make us both anticipate Daddy's return, but it was always someone else, the car's engine drifting into the night, leaving the melancholy thick as corn syrup around us.

I had a lot of time to pole in my canoe in the late afternoons, to sit alone and drift through a canal and think. Through my mind flitted all kinds of dreary thoughts. Virgil Atkins was probably right with his predictions, I concluded. I would die a spinster for sure now, working beside Mama, watching the rest of the world pass by. All the eligible young men would find out about me and no one decent would ever want me. I would never fall in love. Any man who showed any interest in me would show it for only one reason, and once he had his way with me, he would cast me aside as nonchalantly as he cast aside banana peels. Real affection, romance, and love were things to dream about, to read about, but never to know.

Every one of Mama's friends and even people who just stopped by to get Mama's help or buy something we made usually commented about my good looks. It became more and more painful to face them and hear the compliments. Most were surprised I wasn't married or pledged, yet whenever I went to town or to church, it seemed to me that all the respected, decent young men looked through me. I felt invisible and alone. The only place I experienced any contentment was here in the swamp with the wildflowers, with the animals and the birds; but how could I ever share this pleasure with anyone? He would have to have been brought up in the swamps, too, and love it with as much passion as I did. Such a person surely did not exist. I was as lost as a cypress branch, broken, floating, drifting toward nowhere.

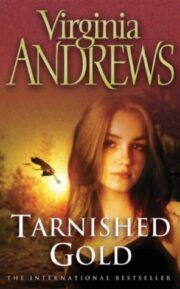

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.