I don’t want to give the wrong impression, though. The Colin pictures were scattered unevenly through, the way one would expect with so peripheral a relative as a great-nephew, no matter how beloved. The bulk of the album was devoted to pictures of a forty- or fifty-something Mrs. Selwick-Alderly, incredibly polished and elegant in the high-waisted skirts and ruffled blouses of the mid-seventies. In the earlier pictures, she was sometimes accompanied by the tall, dissipated-looking man I recognized from the other album as her husband, but he gradually faded out as the pictures went on. Death or divorce? I didn’t want to ask.

Many pictures featured a handsome boy in his early teens, with the same lanky build, shiny dark hair, and fifties’ movie-star features as Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s disappearing husband.

“My grandson Jeremy,” she said shortly, when I asked. “His father died while serving in Northern Ireland in 1969.”

So she did have children of her own. I had wondered about that. Colin’s family did seem to run heavily to the service of Crown and Country. There were more than a few uniforms on prominent display in the albums, including Colin’s father’s. Somewhere along the line, the family had made the switch from freelance espionage to the army. And then there was Colin, who didn’t fall under either. Or did he?

There were no pictures of Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s soldier son — those must have been in a previous album — but there was a dark-haired woman with an impish grin who she identified proudly as “my daughter, Amy. She and her husband live in the UAE now,” she added regretfully. “David works for BP.”

“Do they have children?” I asked, remembering the family pictures on the mantelpiece.

“Three,” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly promptly, flicking over another page. “Tommy started university this year, and the twins, Sally and Posy, are still at school.”

“Do you see them much?” I asked tentatively.

She smiled kindly, as though understanding what I was trying to ask. It made me feel very young and very naïve. “We manage,” she said gently. “And I send them sweets during term-time.”

“Tommy, too?” I asked.

“Especially Tommy.”

As the pages kept turning, Baby Serena showed up on the scene, but this time there were no pictures at all of baby and Mummy, not even the requisite hospital picture. I looked thoughtfully at a photo of an outing to Hyde Park — I knew it was Hyde Park because I recognized the statue of Peter Pan in the background — featuring a tiny Serena in a pram, a sturdy little five-year-old Colin standing to one side, offering the baby a grubby finger to hold, and their father behind, one hand on the handle of the pram, the other resting protectively on Colin’s head, in that way fathers have.

“There aren’t many pictures of the children with their mother,” I ventured, shamelessly fishing.

“Caroline liked to think of herself as a free spirit.” There was more than a hint of acid in Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s voice. Glancing up, I saw that her lips had compressed into a thin, tight line. “I’ve found that ‘free spirit’ is frequently nothing more than a creative synonym for ‘self-indulgence.’ ”

“Was Colin’s mother . . . ?” My voice trailed off. I was on very uncertain ground, dying to know, but afraid to ask for fear she would cease to tell me if I pushed too hard.

Fortunately, Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s eyes were on the album, pulled back by the pictures to a world thirty years away. “Caroline was spoiled first by her parents, then by her husband,” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly said crisply. “What Caroline wanted, Caroline got, or life was made very unpleasant.”

“What about her second husband — Colin’s stepfather?”

A peculiar expression settled across Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s face. “Unfortunately, he, too, was too much indulged,” she said slowly. With a quick, almost convulsive movement, she clamped the cover shut on the album, looking up at me with the bright, apologetic smile of the practiced hostess. “But I am making a terrible waste of your time, rambling on about strangers when it was the Penelope Staines papers you were wanting.”

Dropping the album back into the box, she moved with long-legged grace to the closet, excavating behind the hanging clothes for the next box down.

“She was something of a free spirit, too,” I volunteered, hoping I could work the conversation back around to Colin’s mother and whatever it was she had done to make her aunt by marriage hate her quite so much.

“Penelope?” Straightening, Mrs. Selwick-Alderly glanced over her shoulder at me. “Do you think so? I’ve always thought her much more of a troubled soul, acting out not so much because she wants to, but because others expect it of her. Very sad, I’ve always thought.”

She bent forward to tug at the box and I slid off the bed and scooted down next to her. “Please. Let me.”

The box looked heavy, and for all her ramrod-straight carriage, Mrs. Selwick-Alderly must have been at least eighty, judging from the dates on the pictures in the albums. Remembering the debutante picture on the mantel in the living room, I wondered what it must have been to be a debutante on the very eve of World War II, the last gasp of extravagant parties and great estates and prolonged country house weekends. I remembered her bitter comment about Colin’s mother, the free spirit. By the seventies, when Colin’s mother came into the picture, the world around her must have been all but unrecognizable.

She relinquished the box with good grace, saying cheerfully, “Better you than me,” as she straightened, brushing the palms of her hands against her cream wool trousers.

Clutching the box to my abdomen, I tottered with it to the bed, gratefully dropping it onto the counterpane.

“Ha!” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly, rustling among the contents. “I knew I had it there.”

Inching closer, I tried to peer over her shoulder. Inside, instead of the folios or acid-proof boxes to which a researcher becomes accustomed, was notebook after notebook after notebook, all with metal ring binding and yellowed covers. An autocratic hand, which I recognized from the captions on the photos, had scrawled numbers on the covers.

“These,” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly with great satisfaction, “should be precisely what you were looking for.”

Were they? I tried not to look too dubious.

Perching on the edge of the bed next to the box, she explained, “I spent a winter at the Residency at Karnatabad — oh, years and years ago. Karnatabad was a British construct,” she added briskly, “a district drawn up out of the Ceded Territories, the lands ceded by the Nizam after the second Mahratta War. Lady Frederick’s papers were kept in the archives there. Such a mess they were, too! Generation after generation had simply stuffed books and papers onto shelves without making the least effort to sort them.”

I nodded vigorously in sympathy. I had visited records offices like that in England, including one, which shall remain nameless, where the archivist plaintively asked me if I would mind making a record of whatever papers I came across as I sifted through them since he had never gotten around to doing it himself.

“These notebooks,” said Mrs. Selwick-Alderly, peering down fondly into the box, “are my gleanings from that chaos.”

I couldn’t resist asking. “What made you decide to, er, glean?”

A flicker of a smile showed around Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s lips. “I used to think I wanted to write a novel,” she said, as though it were a great joke. “Mollie Kaye and I both had grand ideas of writing an Indian epic. She actually did it, though.”

Mollie Kaye . . . “You knew M. M. Kaye?” I yelped.

Mrs. Selwick-Alderly nodded, a gentle smile on her lips, as though she were hearing the echoes of conversations once spoken in places that no longer exist. “Yes. We all had a sense, in those days, that the world around us — British India as it had been — was vanishing, and that it was expedient to record as much as we could before it disappeared entirely. It lent a certain urgency to the exercise. And a good thing, too.” Mrs. Selwick-Alderly patted the side of the box fondly. “Not long after my stay in Karnatabad, the Residency was renovated for use as a school and the archives were lost. Someone told me that much of it was simply thrown out. They hadn’t the resources for keeping it,” she said with a sigh, before adding briskly, “Although, of course, primary education was a far more important concern.”

“Of course,” I agreed. And then, because I couldn’t resist, “What was your novel going to be about?”

“Dashing spies,” she said lightly, getting up off the bed. “What else?”

What else, indeed? I wondered if she knew that her great-nephew was currently engaged in writing a spy novel. Or, at least, that was what he claimed. There were still times when I couldn’t help but wonder whether his interest in spies was more than literary. Pretending to write a spy novel could make a very clever cover for other sorts of activities.

“I’ll leave you to it, then. If you have any trouble with the handwriting, don’t hesitate to find me. I have no doubt that the ink is rather faded by now.”

Thanking her, I divested myself of my boots and scrambled up onto the high old bed, tucking my stockinged feet up beneath me. I tentatively lifted the first notebook out of the box. Number Fifteen. Mrs. Selwick-Alderly certainly had been methodical. On the front leaf, she had listed the date she had transcribed it, the translator she had hired to transpose the non-English documents, and the dates and authors of the historical records. If I were half that organized, I would have my dissertation long since done already.

Digging through for a notebook labeled “1,” I found one without any number on it at all. Opening it at random, I saw, in Mrs. Selwick-Alderly’s slanted handwriting, “She waited, breathless, in the lee of Raymond’s Tomb as the dark line of conspirators rode past. To be found would be death.”

Hmm. She hadn’t been joking about that novel, then. I looked speculatively at the notebook. I wondered what would have happened if she had finished it. There were so many novels set around the Indian Mutiny of 1857, but it was hard to think of any set those fifty-odd years earlier, during the Mahratta Wars. It would make a good landscape for fiction.

It also made a good landscape for a dissertation chapter, I reminded myself, forcing myself to put aside the unfinished novel (working title: Shadow of the Tomb ). Clicking on the bedside lamp, which sent a pleasant pool of light across the counterpane, I curled up against the pillows with Notebook 1, a compilation of various letters and dispatches sent by Henry Russell, the exceedingly prolific Chief Secretary to the Resident of Hyderabad.

According to Russell, the Resident had been tearing out his hair about the presentation of the new Special Envoy, Lord Frederick Staines, to the Nizam of Hyderabad at a durbar called for that purpose. No one knew quite what the unpredictable new Nizam might do. The same went for Lord Frederick, who spoke no Persian and had a worrying lack of knowledge about proper court protocol. Embassies had been banished for less.

And to make matters even worse, his wife had insisted on coming along.

Chapter Eight

“What is she doing here?” Alex demanded, as Lady Frederick climbed out of the Resident of Hyderabad’s state palanquin.

The state palanquin, in which James rode with the new Special Envoy, was a testament to what raw money and talented craftsmanship could provide. The tasseled silk curtains, however, hid as much as they concealed. In this case, the presence of an extra individual in the palanquin.

For the duration of the ceremonial procession from the Residency to the Nizam’s fortress, Alex had trotted blithely along beside the palanquin, entirely unaware that the tasseled curtains concealed an additional passenger. Only the Resident and the new Special Envoy had been bidden to the Nizam’s durbar. It had never occurred to Alex — or, he imagined, the Nizam — that the Special Envoy’s wife might take it upon herself to attend as well.

Alex gritted his teeth in a way that boded ill for his dental health. One did not just drop by on a supreme ruler unannounced. Especially not a supreme ruler with a penchant for extemporaneous executions.

All around them, armed guards in steel helmets and gauntlets stood at attention, their bearded faces impassive. There had been more guards than usual in the Nizam’s palace, Alex had noticed, stationed in all of the courtyards through which they had passed on their way to the durbar at which Wellesley’s new Special Envoy was to be formally presented to the Nizam.

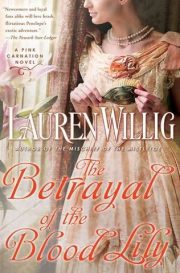

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.