While Sir Leamington Fiske, Daniel Cleave, and the rest of the gang are fictional, the narrative is dotted with genuine historical figures who have been dragooned into service for the purpose of my story. Begum Johnson and Begum Sumroo were both formidable figures of their day, one as grand old dame of Calcutta, the other as ruler of her own principality. In Hyderabad, the Resident (James Kirkpatrick), his marriage to a Hyderabadi lady of quality, his self-satisfied assistant Henry Russell, the courtesan Mah Laqa Bai, the Nizam’s female guards, the leprous Prime Minister Mir Alam, and the mad Nizam Sikunder Jah were all taken from the historical record, as were the French commanders Raymond and Piron. The missing guns and the tension between the Residency and the Subsidiary Force were also fact, although, in the real version, the problem was embezzlement rather than spies. For all details regarding the characters, culture, politics, and anything else relating to Hyderabad, I am entirely indebted to William Dalrymple’s brilliant monograph, White Moghals , which chronicles the career of James Kirkpatrick and his controversial marriage to Khair-un-Nissa.

In some cases, rather than directly employing historical figures, I borrowed their characteristics for my fictional folks. Inspiration for Alex’s father, “the Laughing Colonel,” was taken from James Kirkpatrick’s father, a charming philanderer known as “the Handsome Colonel.” Alex’s troubled brother Jack is loosely based off another real character, James Skinner, the product of an English father and a Rajput mother who committed suicide. Barred from service in the English forces by virtue of his birth, Skinner entered the army of Scindia, a Mahratta leader, under the command of Benoit de Boigne and then Pierre Perron (yes, that Perron). In Skinner’s case, his talent was recognized by Lord Lake, who managed to bend some rules and take him on, in a rather roundabout way, as commander of an irregular cavalry regiment known as “Skinner’s Horse” or “the Yellow Boys,” but Skinner was the exception rather than the norm. In researching Jack’s predicament, I relied on Skinner’s memoirs, The Recollections of Skinner of Skinner’s Horse , as well as the sprightly biography by Philip Mason, Skinner’s Horse , both of which provide a vivid picture of the ambivalent position of Anglo-Indian offspring at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The term Anglo-Indian is often a confusing one, since it is used to describe those Englishmen who spent their lives in India as well as those of mixed English and Indian descent. For those in the latter category, a series of laws passed under the Governor-Generalship of Lord Cornwallis drastically curtailed any chances for advancement. In 1791, anyone without two European parents was banned from civil, military, or naval service in the East India Company. By 1795, they were further barred from serving even as drummers, pipers, or farriers. Those wealthy enough to do so sent their children back to England, where there were no such legal barriers to advancement. Those without the funds were forced to do as Colonel Reid did; to send their sons into the service of local rulers, where the Company’s rules did not apply. The irregular situation created more than a few conflicting loyalties in those affected by Cornwallis’s sanctions. Although Jack Reid is my own invention, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were others in his situation who found the rallying cry of liberté , égalité , and fraternité a seductive one.

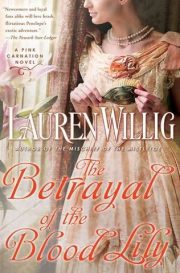

About the Author

The author of five previous Pink Carnation novels, Lauren Willig received a degree in English history from the Harvard history department and a J.D. from Harvard Law, where she graduated magna cum laude. She lives in New York City.

"The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Betrayal of the Blood Lily" друзьям в соцсетях.