The duke makes a minute mark on the paper before him. “I agree,” he says. “She shall get the ambassadorship to France for William, and then I shall tell her to ask for no more. Anything else?”

“The girls she has put in her chamber,” I say. “The girls from Norfolk House and Horsham.”

“Yes?”

“They misbehave with her,” I say bluntly. “And I cannot manage them. They are silly girls. There is always an affair going on with one young man or another; there is always one of them sneaking out or trying to sneak him in.”

“Sneak him in?” he demands, suddenly alert.

“Yes,” I say. “No harm can be done to the queen’s reputation when the king sleeps in her bed. But say that he is weary or sick and he misses a night, and her enemies find that a young man is creeping up the back stairs. Who is to say that he is coming to see Agnes Restwold and not the queen herself?”

“She has her enemies,” he says thoughtfully. “There is not a reformist nor a Lutheran in the kingdom who would not be glad to see her disgraced. Already they are whispering against her.”

“You would know more than I.”

“And there are all our enemies. Every family in England would be glad to see her fall and us dragged down with her. It was ever thus. I would have given anything to see Jane Seymour shamed by a scandal. The king always fills his household with the friends of his wives. Now we are in the ascendancy again, and our enemies are gathering.”

“If we did not insist on having everything…”

“I shall have the Lord Lieutenancy of the North, cost me what it will,” he growls irritably.

“Yes, but after that?”

“Do you not see?” He suddenly rounds on me. “The king is a man for favorites and for adversaries. When he has a Spanish wife, we go to war with France. When he is married to a Boleyn, he destroys the monasteries and the Pope with them. When he is married to a Seymour, we Howards have to creep about and snatch up the crumbs under the table. When he has the Cleves woman, we are all in thrall to Thomas Cromwell, who made the match. Now it is our time again. Our girl is on the throne of England; everything that can be lifted is ours to carry away.”

“But if everyone is our enemy?” I suggest. “If our greed makes us enemies of everyone else?”

He bares his yellow teeth in a smile at me. “Everyone is always our enemy,” he says. “But right now, we are winning.”

Anne, Hampton Court,

Christmas 1540

“If it is to be done at all, it must be done with grace.” This has become my motto, and as the barge comes upriver from Richmond, with the men on the wherries and the fishermen in their little boats doffing their caps when they see my standard and shouting out, “God bless Queen Anne!” and sometimes other less polite encouragements, such as “I’d have kept yer, dearie!” and “Try a Thames-man, why don’t yer?” and worse than that, I smile and wave, repeating to myself again: “If it is to be done at all, it must be done with grace.”

The king cannot behave with grace; his selfishness and folly in this matter are too plain for everyone to see. The ambassadors of Spain and France must have laughed until they were sick over the excess of his wild vanity. Little Kitty Howard (Queen Katherine, I must, I will, remember to call her queen) cannot be expected to behave with grace. I might as well ask a puppy to be graceful. If he does not put her aside within the year, if she does not die in childbirth, then she may learn the grace of a queen… perhaps. But she doesn’t have it now. In truth, she wasn’t even a very good maid-in-waiting. Her manners were not fit for the queen’s rooms then; how will she ever suit the throne?

It has to be me who shows a little grace, if the three of us are not to become a laughingstock of the entire country. I will have to enter my old rooms at this, my favorite palace, as an honored guest. I will have to bend the knee to the girl who now sits in my chair, I will have to address her as Queen Katherine without laughing, or crying, either. I will have to be, as the king has said I may be, his sister and his dearest friend.

That this gives me no protection from arrest and accusation at the whim of the king is as obvious to me as anyone else. He has arrested his own niece and imprisoned her in the old abbey of Syon. Clearly, kinship with the king gives no immunity from fear; friendship with the king gives no safety, as the man who built this very palace, Thomas Wolsey, could prove. But I, rowed steadily upriver, dressed in my best, looking a hundred times happier since the denial of my marriage, can perhaps survive these dangerous times, endure this dangerous proximity, and make a life for myself as a single woman in Henry’s kingdom, which I plainly could not do as a wife.

It is strange, this journey in my own barge with the pennant of Cleves over my head. Traveling alone, without the court following behind in their barges, and without a great reception ahead of me, reminds me, as every day reminds me, that the king has indeed done what he wanted to do – and I can still hardly believe it is possible. I was his wife, and now I am his sister. Is there another king in Christendom who could perform such a transmutation as that? I was Queen of England, and now there is another queen; and she was my maid-in-waiting, and now I am to be hers. This is the philosopher’s stone, turning base metal to gold in the twinkling of an eye. The king has done what a thousand alchemists cannot do: turn base to gold. He has made that basest of maids, Katherine Howard, into a golden queen.

We are coming ashore. The rowers ship their oars in one practiced motion and shoulder them, so the oars stand upright in rows like an avenue for me to walk through, down the barge from my warm seat, huddled in furs at the stern, to where the pages and servants are running out the gangplank and lining the sides.

And here’s an honor! The Duke of Norfolk himself is on the bank to greet me, and two or three from the Privy Council, most of them, I see, kinsmen or allies of the Howards. I am favored by this reception, and I see by his ironic smile that he is as amused as me.

Just as I foretold, the Howards are everywhere; the kingdom will be out of balance by the summer. The duke is not a man to let an opportunity slip by him; he will take advantage, as any battle-hardened veteran would do. Now he has occupied the heights, soon he will win the war. Then we shall see how long it is before tempers fray in the Seymour camp, in the Percy camp, among the Parrs and Culpeppers and Nevilles, among the reformist churchmen around Cranmer who were accustomed to power and influence and wealth and will not tolerate being excluded for long.

I am handed ashore, and the duke bows to me and says, “Welcome to Hampton Court, Your Grace,” just as if I were still queen.

“I thank you,” I say. “I am glad to be here.” Both of us will know that this is true, for, God knows, there was a day, several days, when I never expected to see Hampton Court again. The watergate of the Tower of London where they bring in traitors by night – yes. But Hampton Court for the Christmas feast? No.

“You must have had a cold journey,” he remarks.

I take his arm, and we walk together up the great path to the river frontage of the palace as if we were dear friends.

“I don’t mind the cold,” I say.

“Queen Katherine is expecting you in her rooms.”

“Her Majesty is generous,” I say. There, the words are said. I have called the silliest of all my maids-in-waiting “Her Majesty” as if she were a goddess; and that to her uncle.

“The queen is eager to see you,” he says. “We have all missed you.”

I smile and look down. This is not modesty; it is to prevent me from laughing out loud. This man missed me so much that he was gathering evidence to prove that I had emasculated the king through witchcraft, an accusation that would have taken me to the scaffold before anyone could have saved me.

I look up. “I am very grateful for your friendship,” I say dryly.

We go in through the garden door, and there are half a dozen pages and young lords who used to be in my household loitering between the door and the queen’s rooms to bow and greet me. I am more moved than I dare to show, but when one young page dashes up to me, kneels, and kisses my hand, I have to swallow down the tears and keep my head up. I was their mistress for such a short time, just six months, it is touching to me to think that they care for me still, even though another girl lives in my rooms and takes their service.

The duke grimaces but says nothing. I am far too cautious to comment, so the two of us behave as if all the people on the stairs and in the halls and the whispered blessings are absolutely normal. He leads the way to the queen’s rooms, and the soldiers at the double doors throw them open at his nod and bellow, “Her Grace, the Duchess of Cleves,” and I go in.

The throne is empty. This is my first bemused impression, and I almost think, for one mad moment, that it has all been a joke, one of the famous English jokes, and the duke is about to turn to me and say, “Of course you are queen; take your place again!” and we will all laugh and everything will be as it was.

But then I see that the throne is empty because the queen is on the floor playing with a ball of wool and a kitten, and her ladies are rising to their feet, very dignified and bowing, with immaculate care to the right depth for royalty, but only minor royalty, and at last that child Kitty Howard looks up and sees me and cries out, “Your Grace!” and dashes toward me.

One glance from her uncle tells me how unwelcome would be any sign of intimacy or affection. Down I go into a curtsy as deep as I would show to the king himself.

“Queen Katherine,” I say firmly.

My tone steadies her, and my curtsy reminds her that we have to play this out before many spies, and she halts in her run and wavers into a small curtsy to me. “Duchess,” she says faintly.

I rise up. I so want to tell her that it is all right, that we can be as we were, something like sisters, something like friends, but we have to wait until the chamber door is shut. It must be secret.

“I am honored by your invitation, Your Grace,” I say solemnly. “And I am very glad to share the Christmas feast with you and your husband, His Majesty the king, God bless him.”

She gives a little uncertain laugh and then, when I look promptingly at her, she glances at her uncle and replies: “We are delighted to have you at our court. My husband the king embraces you as his sister, and so do I.”

Then she steps toward me, as clearly she has been told to do only it flew out of her head the moment she saw me, and offers me her royal cheek to kiss.

The duke observes this and announces: “His Majesty the king tells me that he will dine here with you two ladies this evening.”

“Then we must make him welcome,” Katherine says. She turns to Lady Rochford and says: “The duchess and I will sit in my privy chamber while the room is being readied for dinner. We will sit alone,” and then she sails toward my – her – privy chamber as if she had owned it all her life, and I find myself following in her wake.

As soon as the door is shut behind us she rounds on me. “I think that was all right, wasn’t it?” she demands. “Your curtsy was lovely, thank you.”

I smile. “I think it was all right.”

“Sit down, sit down,” she urges me. “You can sit in your chair, you’ll feel more at home.”

I hesitate. “No,” I say. “It is not right so. You sit in the chair, and I will sit beside you. In case someone comes in.”

“What if they do?”

“We will always be watched,” I say, finding the words. “You will always be watched. You have to take care. All the time.”

She shakes her head. “You don’t know what he is like with me,” she assures me. “You have never seen him like this. I can ask for anything; I can have anything I want. Anything in the world I think I could ask for and have. He will allow me anything; he will forgive me anything.”

“Good,” I say, smiling at her.

But her little face is not radiant as it was when she was playing with the kitten.

“I know it is good,” she says hesitantly. “I should be the happiest woman in the world. Like Jane Seymour, you know? Her motto was: ‘the most happy.’”

“You will have to become accustomed to life as a wife and Queen of England,” I say firmly. I really do not want to hear Katherine Howard’s regrets.

“I will,” she says earnestly. She is such a child, she still tries to please anyone who scolds her. “I really do try, Your Gr – er, Anne.”

Jane Boleyn, Hampton Court,

New Year’s Eve 1540

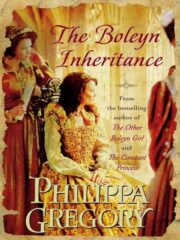

"The Boleyn Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Boleyn Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Boleyn Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.