Arrogance which must be punished, had been the Duchess’s verdict. ‘And yet,’ the doting Lehzen reminded her, ‘a certain queenliness, does not Your Grace agree? A royal determination not to be dictated to?’

The Duchess nodded; but they agreed that such waywardness must not go unchecked.

The child was truthful; one of the finest traits in her character was her frankness and her inability to tell a lie even to extricate herself from an awkward situation. She was subject to sudden outbreaks of temper. These ‘storms’ were regrettable and must be controlled. Only recently when the Duchess had come into the nursery where Victoria was with Lehzen she had asked of Lehzen how Victoria had behaved that morning.

Victoria had in fact been rather more ‘wayward’ than usual and on two occasions had shown temper. The Baroness, not wishing to complain overmuch about her darling but realising that Victoria must always be shown examples of truthfulness, admitted that Victoria had once been a little naughty.

‘No, Lehzen,’ said Victoria. ‘You have forgotten. It was twice.’

And when her mother told her that when she was naughty she made not only her dear mother unhappy but herself also, Victoria considered this and said: ‘No, Mamma, I only make you unhappy.’

They could not be displeased with such a child. In any case she was the centre of their lives. Once Feodora had told her mother that she loved Victoria far more than she loved her, to which the Duchess had sternly replied that a good mother always loved her children equally and was Feodora suggesting that she was not a good mother?

Feodora had merely been wistful, for she loved Victoria dearly; and now knowing that her little half-sister was in the nursery and that at this hour of the day she would not be at her lessons but in the charge of Baroness Lehzen she came to see her so that she might explain to Victoria about her coming wedding.

Victoria cried out in pleasure when she saw her sister; she immediately left the dolls and ran to her.

‘Darling dearest Feodora!’ Victoria put her arms about Feodora’s neck and swung her feet off the floor. Lehzen looked on critically. Scarcely the manner in which a young lady – old enough for marriage – should greet her young sister who was destined to be a Queen; but perhaps as they would soon be parted such a boisterous greeting would be permitted this once.

‘I’ve been telling the dolls that you are going to leave us, darling Feddy, and they do not like it at all.’

Too much fantasy, thought Lehzen. It is time she grew out of the dolls. But the stern Lehzen had to admit that she herself could not grow out of them, so what was to be expected of an eight-year-old girl?

‘Feodora, let us walk in the gardens. May I, Lehzen?’

The Baroness conceded that they might. ‘But put on your fur-trimmed coat and bonnet. The wind is cold.’

Feodora knew the rule: Victoria was never to be left alone; and if the two girls did not stray too far from the Palace a little saunter in the gardens would be permitted. Victoria must not forget that the Reverend Davys would be waiting to give her a lesson in exactly half an hour’s time.

‘We shan’t forget, Lehzen,’ said Feodora holding out her hand. ‘Come, Vicky.’

Such a beautiful girl, Feodora! thought Lehzen. It was well that she was marrying. A reasonably good match but was it good enough for the sister of the future Queen of England? Would Victoria ever be as lovely as Feodora? Perhaps not. She took after her father’s family so much, which was as well, as it would be from that side that the Crown would come to her. But Victoria was Victoria – beauty would not be of such importance to her. There could not be a Prince in Europe who would not be excited at the prospect of marrying Victoria – and perhaps even now in all the Courts of Europe ambitious parents with sons of eight, nine, ten … or older had their eyes on the little jewel of Kensington Palace.

Hand in hand the sisters had come into the gardens.

‘Oh, Sissy,’ Victoria said, ‘it is going to be dreadful when we’re parted.’

‘Dreadful,’ agreed Feodora.

‘You will write to me?’

‘Such long letters that you will tire of reading them.’

‘How can you say that when you know it is not true.’

‘Vicky darling, I know. But I’m so frightened. I’m going to lose you all and have a new husband and I don’t really know him very well. But the worst thing of all is saying good-bye to you.’

Victoria wept openly. She displayed her emotions too readily, said Lehzen; but the Duchess was of the opinion that it showed a tender heart and the people would like it.

‘What is your Ernest like, Feddy?’ asked Victoria. ‘Is he handsome?’

‘Y … yes, I think he is.’

‘As handsome as Augustus d’Este?’

Feodora sighed. Victoria had reminded her of that passionate attachment which had not been allowed to continue.

‘It used to be such fun,’ said Victoria. ‘And Augustus was after all our cousin.’

‘But … he was not accepted as such by the family,’ Feodora reminded her.

‘It is all so complicated,’ complained Victoria. ‘I do wish people would tell me things. Why should Augustus be my cousin and yet not be regarded as such? You know how he always called us “cousins” when we went over into Uncle Augustus’s garden.’

Feodora nodded, recalling those days when she was quite a child, being just past eighteen – she was now a mature twenty-one – and she had been put in charge of Victoria and told not to let her out of her sight. There had been no harm in it. Uncle Augustus, the Duke of Sussex, had a garden among those of the Palace and Victoria had loved to water his plants. And how she used to get her feet wet in the operation and had to be smuggled in before Mamma or Lehzen or Späth saw and feared she would die of the effects. In the garden Augustus would often stroll. He was the son of Uncle Augustus and in truth their cousin, but not accepted as such because the ‘family’ did not regard his father’s marriage to his mother as a true marriage, although Uncle Augustus had been married to her both abroad and in London. It was something to do with that tiresome Marriage Act which said that the sons of the King could not marry without his consent. Well, Uncle Augustus had married without his father’s consent and as his father was King George III who had brought in the Act, the case of Uncle Augustus’s marriage was taken to court and the court gave the verdict that it was not legal. But Augustus the younger believed that it was and that he had every right to court his cousin.

They were happy days, with little Vicky wielding the watering-can and pretty seventeen-year-old Feodora sitting under the tree fanning herself and Augustus coming out as if by accident to talk to her and tell her she was beautiful. How exciting this was after the stern rules laid down in the Duchess of Kent’s apartments in Kensington Palace.

Sometimes the Baroness Späth was with them. Dear old Späth was not nearly such a dragon as Lehzen, and very romantic, thinking how charming it was with Victoria tending the flowers and Augustus and Feodora falling in love.

Victoria had been aware of the intrigue although she was not quite six at the time. In any case it was pleasant to get away from the strict observance of Mamma and Lehzen, for she was allowed deliberately to pour the water over her feet and no one said anything, Feodora being so wrapped up in Augustus’s conversation and Späth being so intent on watching Feodora and her cousin Augustus.

Cousin Augustus was old but very handsome, particularly in his Dragoons’ uniform. As for Feodora she had grown prettier than ever; she had been constantly receiving letters and the Baroness Späth was always tripping from their apartments in Kensington Palace to those of the Duke of Sussex carrying notes from Feodora to Augustus and from Augustus to Feodora.

Once when Victoria had walked in the gardens with Feodora, her sister had whispered that she was going to marry Cousin Augustus and showed Victoria the gold ring he had given her.

‘Then, Feodora, they will be your flowers I shall water.’

‘Yes, dear Vicky.’

‘I shall water them even more carefully because they are yours. And I shall come often to visit you, shall I not ?’

Feodora said solemnly that if Mamma permitted it Vicky should be her very first visitor.

Victoria went back to the nursery and told the dolls the exciting news; but shortly afterwards there was trouble in Kensington Palace. This was when Feodora had told Mamma that Cousin Augustus wished to marry her, at which Mamma was ‘Painly Surprised’, ‘Disagreeably Shocked’ and ‘Very Angry’. It was nonsense it seemed to imagine Cousin Augustus could marry Feodora because Cousin Augustus was not considered to be legitimate and Feodora was the daughter of the Duchess of Kent and although the Duke of Kent had not been her father – for her father had been the Prince of Leiningen, Mamma’s first husband – she was after all connected by her mother’s second marriage with the royal family and was half-sister to Victoria.

Poor darling Feddy! That had been a bad time. Victoria had done her best to comfort her sister. Poor Späth had been talked to very severely by Mamma and had gone about with averted eyes for days afterwards; Lehzen had clicked her tongue every time she saw her, and Victoria was not allowed to water the flowers in Uncle Sussex’s garden because he was in disgrace too.

It was all very sad and poor Feodora had wept and confided to Victoria that her heart was broken.

Victoria presumed it had mended again because Feodora soon began to look almost as she had before those afternoons – though never quite so gay as when she had sat under the trees in Uncle Sussex’s garden; and when not so long ago Uncle King – the most important of all the uncles – had expressed a desire to see his important little niece, Feodora had accompanied Victoria and Mamma to Windsor. Uncle King had been the most impressive man Victoria had ever seen. He was very very old and even fatter than he was old; and when she was lifted on to his lap to kiss him she had seen the rouge on his cheeks. Very strange, but she had liked him – better than Uncle William or Uncle Sussex – and most certainly better than Uncle Cumberland. Uncle Cambridge she did not remember seeing. He was abroad looking after Hanover. But the point was that while Uncle King liked his little niece Victoria very much and took her driving and smiled benignly on her, he could not take his eyes from Feodora and made her sit beside him and kept patting her knee and showing in several ways that he thought her very pretty.

‘I do believe,’ said Victoria, after having witnessed the effect Feodora had on Augustus, ‘that Uncle King would like to marry Feodora.’

Victoria was not the only one who thought that, and shortly afterwards Feodora was sent to Germany to stay with her grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg, and there she had met Ernest Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg who, Grandmamma had made perfectly clear, would be a good husband for her; and what Grandmamma thought proper so would Mamma; and there was no fear of anyone’s being horribly shocked about such a union.

‘He’s a soldier,’ said Feodora, ‘and he’s past thirty … like Augustus.’

Victoria brightened. The more like Augustus the better.

‘He is a very good man,’ said Feodora. ‘There is no scandal about him. Not like Aunt Louise.’

‘What about Aunt Louise?’

‘I don’t know exactly except that Uncle Ernest has parted from her. I think she has done something very wrong. I didn’t see her, but I saw the two little boys. Ernest – named after his father – and Albert who is a little younger. Grandmamma told me he is three months younger than you.’

‘The little boys are our cousins, are they not?’

‘Yes, they are. I wish you could have seen them. Albert is much prettier than Ernest.’

‘I am not sure,’ said Victoria, ‘that boys should be pretty.’

‘Oh they may be at that age; he’s only eight years old, remember.’

‘Yes. Three months younger than I am.’

‘Dear little Alberinchen has the most lovely blue eyes and dimples. He will be very good-looking when he grows up.’

‘And who is Alberinchen?’

‘Albert. It is Grandmamma’s name for him. He is her favourite.’

‘I think I should prefer Ernest.’

‘Why, when you have never seen him?’

‘Because it seems to me that this Albert may be a little spoiled.’

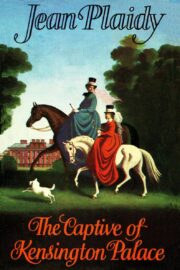

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.