Should he warn her of Conroy? It was hardly the time. He himself was engaged in an adventure of the heart with Caroline Bauer, a charming actress, who was a niece of his favourite physician and friend, Dr Stockmar. He was not given to such conduct and this was a rare lapse; but he consoled himself that Charlotte would have understood; and being so certain of this he could even entertain Caroline at Claremont where he had lived with Charlotte during those months before she had died.

His sister had learned of this attachment and expressed her stern displeasure. That Leopold should have behaved like the immoral people of the Court was distressing. This was perhaps because he had hinted at her relationship with Conroy.

It was clearly better for them to turn a blind eye on each other in that respect. There were ample excuses for both of them, and neither was promiscuous.

So not a word about Conroy. That could come later.

‘Does Victoria understand the position?’

‘Not exactly. She is aware that some great destiny awaits her but she is not quite sure what.’

‘I daresay she has a shrewd notion,’ Leopold smiled affectionately. ‘She is a clever little minx.’

‘I would not have her talk of the possibility. She is so … frank.’

Leopold nodded. But not so indiscreet as her mother.

‘Everyone should take the utmost care,’ he said pointedly. ‘This is a very delicate matter. And I believe Cumberland has his spies everywhere.’

She shivered. ‘I believe he would stop at nothing.’

‘She is guarded night and day?’

‘She sleeps in the same room as myself. Lehzen sits with her until I come to bed. She is never allowed to be alone. I have even ordered that she is not to walk downstairs unaccompanied.’

‘I suppose it’s necessary.’

‘Necessary. Indeed it’s necessary. You know those stairs. The most dangerous in England, with their corkscrew twists and at the sides they taper away to almost nothing. It would be the most likely place that some harm would come to her.’

‘I have Cumberland watched. He wants the throne for himself first and for that boy of his.’

‘But he can do nothing. He comes after Victoria.’

‘And there is no Salic law in this country as in Hanover. But Cumberland would like to introduce it.’

‘He could not do such a thing.’

‘I do not think the people would wish it, but often laws go against the people’s wishes. You know he is Grand Master of the Orange Lodges. I heard that one of their plans is to bring in a law by which females are excluded from the throne.’

The Duchess put her hand to her be-ribboned bosom.

‘It could never be!’

‘I trust not. But I tell you that we should be watchful. William is an old fool; he’s almost as old as George. His health is no good. He suffers from asthma, and that can be dangerous. Moreover, it is just possible that he’ll follow his father into a strait-jacket. They are taking bets at the Clubs that William will be in a strait-jacket before George dies.’

The Duchess clasped her hands. ‘If that should happen …’

‘A Regency,’ said Leopold, his eyes glittering.

‘A mother should guide her daughter.’

‘Her mother … and her uncle.’

The prospect was breathtakingly exciting.

Leopold said: ‘I have been offered the Greek throne. But I have decided to refuse it.’

His sister smiled at him. Of course he had refused it. What was the governing of Greece compared with that of England? When oh when … ? Just those two old men standing in the way. One on his deathbed – although it must be admitted that he was always rising from it, rouging his cheeks and giving musical parties at the Pavilion – and the other a bumptious old fool tottering on the edge of sanity and who was not free from physical ailments either.

It was small wonder that the marriage of Feodora and the pending indiscretions of her brother Charles were of small moment compared with the glittering possibilities which could come through Victoria.

Sir John Conroy, hovering close to the drawing-room, was disturbed. He was always uneasy when Leopold was in the Palace. Leopold was his great rival, for the Duchess’s brother had marked for his own role that which Conroy had chosen for himself. Adviser to the Duchess. In the Saxe-Coburg family Leopold was regarded as a sort of god; he it was who had married the heiress of England, although a younger son and no very brilliant prospects to attract; he had won not only the hand but also the heart of the Princess of England and would have been to all intents and purposes ruler of that country. The Duchess was completely under the spell of her brother.

Hypochondriac! growled Sir John. But he had to admit that for all his brooding on imaginary illnesses Leopold was a shrewd man. Sir John, who made it his business to be informed on everything that might affect his career, had learned that there was a possibility of Leopold’s accepting the Greek throne. That had been joyous news; and when Leopold had refused no one could have been more sorry than Sir John Conroy. He had to accept the fact that Leopold intended to rule England through Victoria, and that was precisely what Sir John wished to do. But how could he hope to influence the Duchess while her brother was beside her?

A lover should have more influence than a brother; and Sir John had always been able to charm the ladies. Lady Conyngham was prepared to be very agreeable; and the poor old Princess Sophia was always excited when he visited her; as for the Duchess, she was devoted to him. One would have thought, in the circumstances, that all would have been easy; but Leopold was no ordinary brother. And Leopold had shown quite clearly that he did not very much like the friendship between his sister and the Comptroller of her household.

What was Leopold saying now? He, Conroy, had made sure that the Duchess was aware of her brother’s affair with Caroline Bauer. That would make him seem slightly less admirable, more human. Leopold was a sanctimonious humbug and it was not surprising that the King could not bear him.

Still, the Duchess did depend on his bounty. It was shameful the way she was treated. Even the King, who was noted for his chivalrous behaviour towards all women, expressed his dislike of her. As for Clarence, he spoke disparagingly of her publicly. But then no one expected good manners from Clarence.

While he hovered close to the drawing-room the Princess Victoria appeared with Lehzen.

Victoria was saying: ‘I do hope dearest Uncle Leopold will not be too upset because I was not at the window. He has come early. Oh dear, how I wish I had been there.’

‘I daresay His Highness will understand,’ said Lehzen.

This adoration of Leopold was really quite absurd, thought Conroy.

A sneer played about his lips. Victoria noticed it and did not like it. She had come to the conclusion that she did not really like Sir John. There was something about him that disturbed her. It was when he was with Mamma. Sometimes when he was with Aunt Sophia too; and there were times when his eyes would rest on Victoria herself speculatively.

She had never spoken the thought aloud but it was in her mind. She did not like Sir John.

‘Have you something on your mind?’ The sneer was very evident. He never treated her with the same respect as she was accustomed to receive from the Baroness Späth – and Lehzen who, for all her sternness, always conveyed that she was aware of her importance.

‘I did not care to keep my uncle waiting,’ she said coldly.

‘He hasn’t waited long. You were here almost before the summons came.’

‘If I wish to be here, I shall be,’ she said in her most imperious manner.

But Sir John Conroy was not to be intimidated as a music master some years before. Doubtless, she thought, he will report this to Mamma and say that I was arrogant and haughty. But if I wish to be arrogant and haughty, I shall be.

‘Ha,’ laughed Sir John, ‘now you look exactly like the Duke of Gloucester.’

What a dreadful thought! The Duke of Gloucester. Aunt Mary’s old husband and cousin. Silly Billy, they called him in the family; he was looked on as rather stupid and now that he had married the Princess Mary, had become a difficult husband.

‘I have always been told,’ she said coldly, ‘that I resembled my Uncle, the King.’

‘Oh no, no. You’re not a bit like him. You grow more like the Duke of Gloucester every day.’

She swept past, with Lehzen in her wake. Sir John laughed but with some misgiving. It was silly to have upset the child just because he was angry about Leopold. Old Lehzen too! She was no friend of his.

He would get rid of her if possible. But he could see he would have to be careful with Victoria.

Smarting from her encounter with her mother’s Comptroller of Household Victoria went into the drawing-room where the sight of dearest Uncle Leopold seated in his chair, his dear pale face beautiful beneath his curly wig, made her forget everything else.

‘Dearest Uncle …’

She ran to him, throwing ceremony aside. After that horrible encounter with Conroy she needed the protective comfort of Leopold’s arms more than ever.

Feodora, being dressed for her wedding was a little fearful, a little tearful. She was not afraid of her bridegroom; in fact she liked him. Since her match with Augustus d’Este had been frowned on she had faced the fact that she must marry a Prince who was chosen for her; and her Ernest was by no means unattractive. She had compared Ernest with Augustus and now that Augustus was out of reach it seemed to her that Ernest did not suffer too much from the comparison.

All the same she was leaving Kensington which had been home to her for so long; but she had to admit, though, that apart from leaving Victoria and dear old Lehzen and Späth, she would not mind so much. Her recent trip to Germany had made her feel that she could be very happy there. It was leaving her dear little sister that was so upsetting.

She realised that she had not included Mamma in those she would miss. Well, to tell the truth, she would not be sorry to escape from Mamma. There, she had admitted it. But she would not allow herself to say it. Dear little Victoria was condemned to imprisonment … because that was what it was … in a way.

She should therefore be gay and happy; and so she would be if it were not for leaving Victoria.

Victoria had come in to see the bride. Lehzen hovered. Oh, why could we never be alone even for a little while!

‘Dearest Sissy! You look so beautiful.’

‘All brides look beautiful. It’s the dress.’

‘No bride looked as beautiful as you.’

‘Vicky, you always see those you love in a flattering light.’

‘Do I?’

‘Of course you do, you dear Angel. And you look lovely yourself.’

Victoria turned round to show off her white lace dress.

‘I am going to miss you so,’ said Feodora tremulously.

‘It is going to be terrible without you.’

‘But you will have Uncle Leopold, dear Lehzen and Späth … and Mamma.’

‘And you will have Ernest. He is very handsome, Feodora, and Uncle Leopold says he is a good match.’

‘Oh yes, I like Ernest.’

‘But you must love your husband. And just think there will be the darling little children.’

‘Oh, not for a while,’ said Feodora.

‘What a lovely necklace.’

‘It’s diamonds. A present from the King.’

‘He loves you. I think he would have liked to marry you.’

‘Oh, he is an old, old man.’

‘But a very nice one. I think that next to Uncle Leopold he is the nicest man I know. And he is a King.’

‘He is coming to the wedding. He has promised to give me away.’

‘I don’t think he will like that … giving you away to Ernest when he wants you himself.’

‘Oh, Vicky, what extraordinary things you say!’

‘Do I? Perhaps I say too rashly what comes into my mind. Lehzen says I do.’

‘Oh dear, when I think of you here without me, I shall weep, I know I shall.’

‘But you will come to Kensington and perhaps I shall pay a visit to Germany.’

‘I shall have to come to Kensington for they will never let you out of their sight.’

Victoria sighed. ‘I wish they would let me be alone with myself … just for a little while.’

‘I know how you feel, darling. I think I am going to be freer now.’

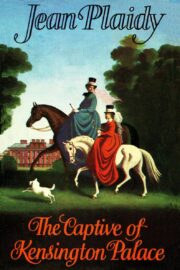

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.