I SMOOTH OVER my sari to make the bulge of the pomegranate at my waist less conspicuous as Madhu leads me into Mura’s section of the compartment. It is surprisingly shabby. Areas of fresh white paint compete with expanses of peeling railway-regulation green, as if someone abandoned a renovation project midway. One entire side still has sleeper berths stacked two high running along its length, and the floor shows gaping holes where walls and dividers have been yanked out. Could this really be the den of someone working for the great and mighty Bhim?

Mura sits in one of the lower berths, cracking open peanuts. He does so with the fingers of only his left hand, extracting the kernels and tossing them into his mouth in a single compulsive arc. He is small but bulbous, with a head larger than his body, as one might expect of someone employing a lot of brainpower—an accountant, perhaps. I notice an unhealthy sheen to him, an oiliness that oozes out of his skin and glistens on his scalp. Perhaps he has too many peanuts in his diet.

Madhu explains my presence and withdraws, closing the door behind her. The makeup must have worked, because Mura does not question me about my age. “Can you dance?” he asks instead.

“A little. Guddi said she could teach me.”

“Ah, Guddi. She’s so innocent, isn’t she? Do you know, when I went to fetch her, she asked if she could bring her five-year-old brother along to meet Devi ma as well? These villagers—they’re all so child-like. One can’t even begin to explain the ways of the world to them.” Mura takes off his thick accountant glasses and wipes his face with a handkerchief, and I wait to find out what he is getting at.

“Of course, you, being from the city, must know things work a little differently. For instance, despite whatever blemishes your layers of makeup might be trying to hide, suppose I choose you for Devi ma. The question then arises, what would be in it for me?” Mura’s eyes bulge a little behind their lenses, like those of a child reminded of a favorite treat.

“I don’t have much money, if that’s what you want.”

“Oh, no—I meant nothing so crass. But you do see my point, don’t you? City people are different from villagers—more willing to be a little guileful if it gives them an advantage. With them—with us—there’s no shame in asking for fair give-and-take.” He pats the seat beside him. “Why don’t you come here and sit with me on the berth? If nothing else, as a small reward in recognition of all I’m doing for our community?” He breaks open a peanut and holds out the kernels in his hand, as if I’m a bird he’s trying to attract.

I ignore his offering. “If you don’t mind, I prefer to stand.” First the hospital Romeo, then Hrithik, now Mura—has my body pumped out some special pheromone today to provoke all these advances? Why am I suddenly so popular?

Mura shakes his head. “Unwilling to even sit by my side. Not even a little generosity of spirit.” He looks at me reproachfully. “Perhaps then Mura will have to stand as well.”

Just then, I hear the screeching sound of the engine brakes being applied. Peanuts sail through the air, Mura slides to the floor and I almost go flying as well, as the train slows, suddenly, violently. We come to a halt, and Mura gets up sputtering. “That driver, he must be mad to make a stop like this. You just wait here, I’ll go investigate.” He exits from the door to the girls’ room, and I hear a bolt being drawn closed on the other side.

This is my chance to escape. I go to the door and call out the girls’ names in a whisper. “Anupam? Guddi? Madhu?”

“Yes, Didi?”

“Guddi, can you open this door?”

I hear a giggle, and some muffled conversation. Then Anupam answers. “Didi? Mura chacha said not to let you out.”

“It’s just for a minute. I have to use the bathroom.”

More discussion follows, and then Guddi speaks again. “We’d have to check with Madhu didi first. She’s stepped out with Mura chacha. They won’t be long.” Anupam giggles in the background.

I decide to try a window. I pry apart two of the horizontal bars, but the widened space is barely big enough for a cat to squeeze through. Searching the compartment for something to use as a crowbar, I notice how much rustier the windows get towards the far end. The last window only has two bars still in place, one of which simply crumbles when I test it. Just as I knock out the remaining bar for an opening I can comfortably squeeze through, Mura returns.

“That stupid engineer. He wanted to return to Dadar, got cold feet going through Mahim. Some crazy idea of taking the Central Line to Ghatkopar, then switching over to the new metro rail. Never mind that those tracks are twenty meters up in the air. I told him there was absolutely no danger, that Bhim had personally arranged our passage.”

I stand in front of the window as he talks, trying to cover the absence of the bars with my frame. Perhaps he won’t notice the alternate plans I’ve made.

“It really wouldn’t have done you any good even if you had managed to crawl through,” Mura says softly as we start moving again. His voice sounds concerned, sympathetic. “Haven’t you had a chance to see what’s outside?” I look through the window at the pools of stagnant water by the tracks, at the line of shanty houses running alongside. Plots of spinach and salad leaves go by, just like anywhere along the suburban rail corridor.

“You don’t realize, do you?—that fork at Dadar the engineer wanted to take? We’re in Mahim now, the Muslim side he dreaded. It’s the heart of their stronghold—when the killings began in force, the first area they barricaded themselves off in. But don’t worry, we’ve paid them off to let us pass—they think we’re just a harmless bunch of Christians headed back to Bandra over the railway bridge.

“Of course, you’re welcome to go your own way. But there’s no telling what they’ll do to you the minute you step off the train. Especially when they see you in that pretty Hindu bridal outfit.”

WHAT SENT BOMBAY careening most irrevocably towards its breakup into Hindu and Muslim sections was the Bandra-Worli sea link. Cutting across the sea to avoid crowded suburbs like Dadar and Mahim, the bypass connected the south to the north in ten minutes flat (seven with Uma driving). “Look at us,” she’d say, zipping us over the structure that had taken sixteen billion rupees and a decade to build. “We’re a top-tier international metropolis now—no less than San Francisco or Sydney.”

Perhaps it was the acclaim lavished on the bridge as the crown jewel of Indian engineering that attracted the HRM’s attention. The organization announced, out of the blue one day, that although operational since 2009, the structure had never been consecrated. For the next City of Devi project, massive religious processions would march all through Mumbai to converge at the bridge, where Hindu priests would confer their blessing and rename it the “Mumbadevi Sea Link.” To further stoke this “new and incendiary mischief” (as The Indian Express called it), the HRM would fly in the top leaders of all the major right-wing organizations in the country to join in the ceremony.

By the time I turned on the television that morning, the toll booths had already been doused with vermilion and the swell of participants had reached the cantilevered section of the bridge. HRM’s Doshi appeared in a close-up, trying to smile through the sweat pouring down his face. He struck a coconut on the concrete, breaking it open only after three attempts. Holding the two halves aloft as if he’d aced a magic trick, he ascended a small podium and began to speak.

“Many centuries ago, in the time of the Ramayana, our ancestors proved their engineering prowess. They built a bridge from India all the way south to Lanka so that Lord Ram could walk across the sea and bring back his Sita Devi. Today, Hindu engineers have repeated the feat of their forebears so that we can make a similar journey south, from Bandra to Worli.” I switched the TV to another channel, but Doshi appeared on that one too, thanking Mumbadevi for showering her protection and blessings on the bridge.

Just as I readied to change the channel again, the camera drew back to an odd wide-angle aerial shot of the cable suspension spans soaring forty stories into the air. What caught my eye was how one of the central towers holding up the cables seemed to tilt out of the screen towards me. The giant fireball, accompanied by the sound of the explosion, came an instant later. Images flashed on the screen in jerky succession—people running about and leaping off, more blasts spewing debris and smoke, the two cable spans parting like the wings of a dying butterfly to collapse towards the water and sink. Each time I thought the mayhem had ended, a fresh explosion knocked out another segment. Eventually, as I stared aghast at the TV screen, only the smoking frame remained.

One hundred and eighty-two people perished that morning, including Shrikant Doshi and much of the leadership of the HRM and its allies. “Stay indoors,” my father called to warn me, “there’s going to be riots all over the city.” Sure enough, rival factions plunged eagerly into a contest to see who could massacre the most Muslims—not just as reprisal (even though the explosions had all the hallmarks of sophisticated terrorists), but also to prove themselves the fiercest and most ruthless, and hence most deserving to fill the power vacuum. Our March for Unity failed to impress them, as did the anguished editorials composed by newspaper pundits.

The single bloodiest incident occurred that weekend at Haji Ali. A rampaging mob led by a previously unknown upstart charged down the walkway across the bay to the island on which the mosque stood. Bhim’s army beheaded men as they prayed, dragged women out and raped them in the courtyard, impaled babies on sharpened sticks driven into the rocky beach. They also meticulously videotaped everything. Even censored for television, the clip broadcast that evening was so disturbing that both Karun and I had to look away.

Others, however, reveled in the images. The video propagated its savagery all across the country, its frames leaping from screen to screen through the population’s billion-plus cell phones. (My father, to his horror, even received a digitally altered version casting the attackers as Muslims and their victims as hapless Hindu pilgrims.) After months of aimless venting, Superdevi-charged mobs in towns and villages finally found a focus for their hooliganism. The news turned so grim that Karun and I had to suspend our breakfast ritual of reading out to each other from the paper: twenty Muslim villages annihilated in western Gujarat, forty-one Hindu children in Lucknow circumcised with the same sharp stones used afterwards to bash in their skulls, Christians burnt alive in churches, Sikhs butchered on the street. Every group seemed to join in lustily, as if the national goal of religious integration had finally triumphed, and the bloodbath were a grand celebration of multiculturalism, of equal opportunity.

When Bhim wrested control of the HRM, we all heaved a sigh of relief. The competition for power had ended, the killing would finally stop. All through his ascendancy, we’d heard different myths about Bhim—a businessman kidnapped and tortured by Muslims, a professor whose family terrorists had wiped out. But nobody knew what he claimed to stand for—not until the rally at which he declared himself a fighter for peace. “I pledge to set aside past bloodshed, extend minorities an olive branch,” Karun recited from the newspaper the next morning. “From now on, my goal is to promote harmony, to advance industry and science and art.” Supposedly, Bhim’s model was to be Ashoka the Great, the ancient Mauryan emperor who united India with unrestrained savagery, but then ruled with great compassion and benevolence. In the following weeks, reports streamed in about his attempts to get city dwellers to join hands with rural followers, his dynamic success in connecting with the educated young. Even Uma toyed with the idea of subscribing (out of sheer curiosity, she told my enraged father) when Bhim inaugurated his TwitterXLP account.

He overlooked one detail: while the HRM may have crowned him their emperor, the country had different ideas. In the long-scheduled national elections that month, the HRM was soundly trounced. Enraged by this humiliation (which he blamed on the “cancerous seeds” sown by minorities) Bhim not only jettisoned Ashoka, but decided the HRM would bypass the political process altogether. The violence from the power struggle had never really died down—it still burned in the background, as self-sustaining as a nuclear reaction by now. Bhim stoked its fires, channeling its bloodthirst into a campaign to rid the country of Muslims once and for all.

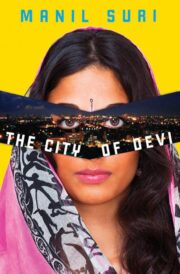

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.