After that, I had much more success in overcoming Karun’s decorum, his squeamishness. The dove nest became our love nest, but I pushed his boundaries to include other venues as well. During an uncrowded matinee at the Regal, we treated the empty last balcony row to action it probably had never before witnessed, either on screen or otherwise. At a secluded spot in Versova, north of Juhu, we attempted it while waist-deep in the sea—the waves kept ruining our rhythm, so we had to find a spot under the palms to finish. I even got Karun to give me a hand job while barreling down Marine Drive on the top deck of an empty 123 bus late one evening. The experience proved so memorable that it moved the Jazter to poetry: “Salt air flew as the Jazter blew,” “Sea breezes rushed as the Jazter gushed,” “Scenery whizzed as the Jazter jizzed”—there’s a haiku in there somewhere, if he can get the number of syllables right.

Karun’s amenability to these escapades surprised me. I could tell he enjoyed sex, but I didn’t get the impression he hungered for it—it would never be the all-consuming force that fueled the Jazter. Rather, it occupied a single drawer in the orderly portfolio of his needs, one whose replenishment he could control and monitor. Perhaps he viewed our trysts as experiments, contributions to a broader ethnographical study on the congregational patterns and mating behavior of homosexuals. More likely, what attracted him was the chance to set responsibility aside and regress to a reckless adolescence. “I feel like a kid again,” he said each time we assembled the train set or rode the roller coasters at Essel Park, and I think our undercover adventures generated a similar thrill.

I enjoyed these naughty bits as well, despite once having been enough with every other conquest in the park. What puzzled me was all the extra time I still expended on dates with Karun, given that I’d already prevailed in my shikari motives. We journeyed to far-off food stalls and Udupi restaurants to unearth the best vada-pav and idli-sambhar (he only had money for holes-in-the-wall). Some evenings, we strolled along Marine Drive, perhaps sharing an ear of roasted corn. On weekends, I lugged my books over to his hostel, so that we could sit together in his study hall and prepare for our upcoming exams.

Perhaps what attracted me to all these extracurricular activities was the way Karun’s preoccupations seemed to dissolve in my company. I loved watching his seriousness lift and a more carefree personality emerge, like a face behind purdah only a spouse could unveil. My favorite game was to see how often I could provoke his smile. Each time I scored, a jolt of realization ran through me—this was something only I could accomplish, a privilege extended only to me. He liked to tell me about his parents, to compare childhood notes about fending for ourselves. I made sure we fucked whenever the conversations got too emotional or too long—we weren’t lesbians, after all.

His smartness pleased me, even though I found his atoms and galaxies only mildly interesting. (Perhaps his own family’s erudition biases the Jazter more deeply than he cares to admit.) One morning, Karun called to excitedly announce a link between our two fields—he’d come across an article on pricing financial derivatives using quantum techniques.

I took him home for dinner with my parents—something unthinkable with any of my former liaisons. “It’s so nice to meet Ijaz’s friends,” my mother declared, and joined us for Scrabble on the dining table afterwards. My father beamed benignly and commended me for taking such an interest in physics. (A physicist, I wanted to correct—I was taking such an interest in a physicist.)

The only person not so oblivious was Nazir. “I could make some tea,” he offered, “if sahib will be retiring to his room later with his friend.” But I felt too self-conscious taking Karun to my room, so we contented ourselves with some footsie under the table instead.

Nazir put his perceptiveness to good use. The next time my parents left on a trip, he demurred when I offered him some time off as well. “It’s so expensive to go to my village. If only I had the two hundred rupees for train fare.” It took some bargaining before he settled for a hundred, with an extra twenty to cook the biryani.

THE THREATENED BOMB has done what a thousand traffic engineers couldn’t—made walking through even the most congested areas in the suburbs a breeze. Although baskets and crates and handcarts lie discarded everywhere, the cars that normally choke the streets are gone—driven far off by owners in search of safety. The menacing specter of the Limbus has scared away the pedestrians. Even the ragpickers have vanished, with the result that an unclaimed bonanza of paper swirls luxuriantly at our feet.

An imposing figure stands guard in the center of the traffic island up ahead. Sarita and I both freeze at the same instant, as though motionlessness will magically confer camouflage, even though we are in the middle of the street. Then I note the apparition’s abnormal height—it rises even taller than the traffic lights. “Nothing human can be that size,” I whisper, and we cautiously resume our advance.

Sarita recognizes it first. “It’s one of those Mumbadevi statues. The warriors the HRM installed during their ‘City of Devi’ days.”

Except someone has chopped off all six arms. The neck has been hacked through and the head turned upside down. Dirt fills the eye sockets; lips, nose, ears have been chiseled away. Hatchet marks and paint splotches cover the whole body in an angry patchwork. With her vandalized torso and rearranged parts, Mumbadevi looks like a sculpture composed by one of the more misogynist cubists—Picasso, perhaps. And yet she still stands, too heavy to topple over from her pedestal, gazing with her desecrated eyes at the destruction of her city, managing a mute dignity in the dying sun. “We’re definitely getting closer to the Limbus,” I say.

Behind Mumbadevi stretches a boulevard lined with shuttered storefronts. Every third or fourth shop is charred—in one, I think I spot the remains of an arm sticking out of the debris. Mahim has not been spared by the bombing, Sarita remarks, but I tell her it looks like Limbu handiwork. “They probably targeted the Hindus to drive them out of business when the war first started.” I position myself between her and the shops so she doesn’t glimpse any hiding body parts.

My partner in extreme tourism has become much more inquisitive, I’ve noticed—asking me several questions about my background and job. I answer truthfully as far as possible, confident she won’t figure me out. When it comes to explaining why my mother’s in Jogeshwari, though, I get carried away—spinning a heartrending tale about early widowhood and property-snatching relatives. “Why aren’t you married?” she throws in, as if trying to trip me up after getting my defenses down. I give my standard reply of not having found the right person yet. But I’m hoping you will lead me to him.

Sarita is quite forthcoming when I ask her questions in return, except when I try to learn what her husband might be doing at a Bandra guesthouse. Then she responds in monosyllables, and I wonder if she’s stonewalling. It occurs to me that she simply might not know, that Karun may not have confided in her. Might this bode well for the Jazter’s chances?

The silence of the boulevard makes the cacophony of billboards covering the building façades even louder than usual—there are exhortations on the behalf of Suzuki cars, television serials, skin-lightening creams. “New Singapore Masala Chicken Pizza!” a sign screams outside an abandoned Pizza Hut, reminding me I haven’t eaten since breakfast. The door is missing, and though I’m wary of grisly discoveries lurking in the interior, we enter. Inside, the place has been meticulously looted—even the countertops in the kitchen have been ripped out. Only the wall posters remain—a fading explanation of the ill-fated “City of Devi” computer mouse promotion flanked by announcements for more new flavors: “Cauliflower Manchurian,” “Texas Tandoori,” even the improbable “Swedish Ginger-Garlic.”

I’m getting increasingly faint imagining all these pizzas, when we hear the bells. I pull Sarita deeper inside, but then see through the window that the sounds come from children on bicycles. They circle outside the door, perhaps a dozen boys in scruffy shorts and undershirts, some so young their feet barely touch the pedals. “You won’t find anything in there,” one of them shouts. “To eat, you have to go to the mosque—at eight p.m., they feed anyone who shows up.”

I wave them away as we emerge, but they follow us down the street, ringing their bells and crisscrossing our path. “What a lovely wife you have,” they hoot. “So sexy in that red sari without her burkha—too bad the Limbus will beat her up to teach her a lesson.”

The oldest in the group, a boy of about twelve with long scabs on his cheeks, stops his bicycle right in front of us. “Come this way.” He gestures towards a narrow alleyway trailing off. “The guards on the main road have rifles. They’ll only let you through if you pay a lot.”

Although I’m confident I can prove I’m Muslim (if reciting all the Koran verses I know by heart doesn’t do it, there’s always the anatomical identity card), I lose my nerve. Sarita would present a problem even if less flamboyantly dressed, plus what if they find my gun? I take her hand and follow the boy down the alley, wondering if he’s leading us into a trap. The feeling intensifies as he ushers us through a large wooden doorway into an empty compound, then chains his bicycle to a post and disappears up some steps. I’m looking for rifles to start blazing at us from the windows circling the compound when the boy returns. “Here,” he says, handing Sarita a length of brown fabric. “Put this on.”

“What is it?” she asks, holding up the sturdy cotton material. “It looks like a tablecloth.”

The boy shrugs. “It used to be. But now it’s a burkha. My mother cut out the eyeholes and sewed together the ends—she used to cover my sister with it while shopping before we had a proper one made. I’ll let you have it cheap—just fifty rupees.”

Sarita declares she’s not about to wear a tablecloth, but I take it from her and give the boy a twenty, who smiles and says his name is Yusuf. He scampers to a door on the other side of the compound. “See?” he says, throwing it open. “You’re now past the guards.”

We step into a market lane—so thronged with humanity that it almost makes up for the desolation of the neighborhoods we’ve trudged through. Unlike my last time in Mahim, every last woman is now enveloped in a bulky burkha and most of the men sport skullcaps and beards. (Did they begin growing them the minute war was declared?) Flaming torches affixed to the energy-sapped lampposts give the scene a festive, medieval air. Sarita stumbles along beside me, looking like a child playing “ghost” under her tablecloth. “I can’t believe it,” she suddenly exclaims, pointing at a man sitting by the road selling pomegranates. She buys a large red specimen for fifty rupees to replace the one lost in the train. “How that swine in Crawford Market cheated me!”

“This one cheated you too,” Yusuf says. “I could have got it for fifteen.”

Both the quality and variety of wares being hawked from the pavements amaze me. The pomegranates, like the glistening apples and pears and oranges, nestle in individual foam compartments—packing usually reserved for only the choicest imported fruits. Tins of meat and fish, practically never spotted outside of tony South Bombay boutiques, lie stacked in bountiful, artistically spiraling pyramids. One vendor sells nothing but five different kinds of toothpaste—upon closer examination, the brands are all unfamiliar (“Denticon,” “Protect,” “Kingcol”) with writing in English and Arabic, even Chinese! Where does all this come from? I ask Yusuf. The question stumps him initially, but then he brightens. “We must manufacture it all here in Mahim,” he proudly declares.

We haggle over how much he will charge to lead us to the Hotel Rahim. His first bid is a new pair of Adidas, being sold by one of the hawkers for three thousand rupees, but he soon capitulates when I hold fast to my offer of another twenty. “That’s the way to the one restaurant still open,” he says, pointing down a narrow lane as we pass a row of old buildings. “People claim they’ve started chopping up dogs to use in their kebabs, but my mother says that’s just the way tinned meat tastes. And if you go further, you’ll come to the main road with the mosque—you can join the line if you want to eat for free.”

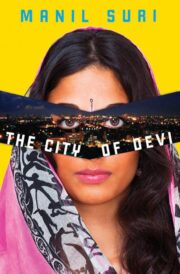

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.