The question I can’t bring myself to confront Rahim with is where he fits in all of this. Is he a stooge, a Pakistani lackey? I take a bite of the pineapple pastry I’ve selected from the buffet—the custard cream filling slides smoothly down my throat. Do I thank the ISI for this treat?

It turns out my cousin has an even more sinister patron. “It happened while he was here on a clandestine visit—a VIP who loved my hospitality so much that he took over all my loans for me. The loans that were threatening to wipe out your poor Auntie Rahim. Can’t tell you the name, because you’ll recognize it—all I’ll say is he lives in Dubai and Karachi now, but still controls most of Mahim.”

“You mean a gangster? Like Dawood or Shakeel?”

Rahim titters. “Whoever it is, the ISI has full faith in him—they’ve entrusted their entire operation to his men. He still makes it personally to Bombay more often than people might imagine—always comes in by sea with a large entourage. As do his associates, some of whose names you would also recognize—we’re actually quite full most nights. That’s why I keep dinner ready—I never know who might show up, and when.”

“So what you’re telling me, basically, is that you work for the mafia underworld. Maybe one of the same dons who fled to Dubai after slaughtering hundreds in bomb blasts all over the city?”

Rahim stiffens. “Perhaps you need to look around before you point any fingers. Check to see who’s being slaughtered and who’s doing the slaughtering. Just the massacres in the past year alone—have you been keeping track? Gaza to Germany, Houston to Haji Ali, not to mention all the internment camps. We’re being annihilated, Jaz—if we don’t take help from whoever offers it, there might soon be no Muslims left. Besides, this isn’t some cheap two-rupee street hooligan we’re talking about—my patron is someone cultured, someone sophisticated, someone who appreciates foie gras with every meal.”

“Someone who’d still have no compunction in blowing up all of India. Or perhaps that’s too passé—thinking you owe your homeland anything.”

“How sweet—the little pup calling Auntie’s patriotism into question. After spending half its life abroad, no less. Well let me tell you, my flag-waving Jazmine, while you were swilling beer and chocolate with the Americans and Swiss, I was being bottle-fed the Indian dream. Nehru and Gandhi, Saare Jahan Se Achcha, the whole secular ideal. So what if our government perpetrated years of carnage against its own citizens in Kashmir? Or systematically filtered Muslims out from its armed forces and police regiments? Or turned a blind eye each time the Hindus decided to here and there roast a few minorities alive? None of it really affected me. I was content to keep singing patriotic songs, brand Pakistan the enemy, march against terrorism with all my fellow brainwashed Muslims hand in hand through the streets.

“Then the HRM started its Devi rampaging. Beatings, rapes, murders—they all happened to people I knew, people alarmingly close to me. On Linking Road, I personally saw the corpses in their shops: blackened mummies still sitting at the till, waiting to give change back from a twenty. Entire families wiped out and nobody did anything—not the government, not police, and certainly not our fellow Hindu citizenry.”

“But that’s exactly how they want you to think—Hindu versus Muslim instead of just Indian.”

“It doesn’t matter what one thinks. You can scream you’re Indian, you can disavow your religion, you can even be the next incarnation of Krishna for all your Hindu countrymen will care. Their HRM will pull down your pants and check your foreskin and slaughter you just the same.”

Rahim takes a deep breath. “Listen, Jaz, you’ve known me for years. Just look at me, just look at my fabulousness—I simply can’t conceal who I am. You can never imagine what a hard time I’ve had all my life fitting in. But all the insults and abuse I’ve endured have taught me one thing: how to protect my own skin. Before being an Indian, before being a Muslim, I’m a survivor—prepared to do whatever’s needed to stay alive. If you and your friend want to come through this war, I’d suggest you start doing the same.”

AS WE SIP OUR after-dinner coffee, I remark on the fact that none of Rahim’s big-shot gangster sponsors seems to have checked in. “It’s still early,” he says. “They find it hard to give me notice, now that mobile phones don’t work.”

“So it’s nothing to do with the nuclear firecracker that Pakistan might be lighting this week?”

“You mean those rumors? The phones and the internet?” Rahim waves his hand dismissively. “That’s not Pakistan, that’s Bhim, trying to empty out the city.”

“Why would he want to do that?”

“Who knows? Perhaps he figures it’ll be easier to take over. Or perhaps he’s just hoping to scare the Indian army into a preemptive strike. God-willing even our military isn’t so stupid. The important thing is that Pakistan would hardly sink so much into their colony here if they intended to blow up the entire city.”

“So it’s just a coincidence that your hotel is empty. Did you at least have a lot of guests yesterday?”

Rahim ignores my question. “They’ll be here soon, believe me. I’m sure they’re already on their way.”

By nine, he’s plainly worried. He tries his cell phone repeatedly, as if it might have miraculously started working. He sends some of his servants to the Limbus to check if they’ve heard anything. He reiterates his bomb theory several times, coming up with even more far-fetched motives that might explain Bhim’s ploy (to scare up more followers, to feed his own vanity). At nine-thirty, the doorbell rings. “They’re here,” Rahim announces, both triumphant and relieved. He rushes down the stairs to personally usher in his guests.

He returns after a while. “We need to clear out from here—my clients prefer to dine privately. Let me show you to your rooms.” Sarita is alarmed at being ushered into her own separate suite, but he assures her I’ll be just down the hall. “The sheets are Egyptian cotton—you’ll sleep so soundly you’ll forget all your worries.”

We bid Sarita good night and Rahim walks me to a room down the corridor. The minute we’re inside, his expression changes. “That was the Limbus. They’re on to you. They ambushed a train today and took a Hindu prisoner or two—they’re looking for the ones who escaped. A kid named Yusuf says he led you here—they roughed him up a bit after a friend ratted on him. I told them I hadn’t let anyone in, but they still wanted to search the hotel. It’s only when I reminded them who the owner is and how angry he’d get that they relented—they’re milling about outside now, waiting for permission from their higher-ups.” He pauses, then looks at me gravely. “She’s Hindu, isn’t she? I should have guessed—that way of sliding her sari over her hair.”

My mind races. “Do they have the rear covered as well? I saw an alley between the buildings—there must be a back entrance, correct?”

Rahim looks at me sadly. “There is, right through the kitchen, and it would make a perfect escape. Except I can’t allow it—my boss would kill me if the Limbus didn’t. But fortunately, there’s a simple solution to all this. We’ll tell them the truth—that you’re Muslim, that we’re related—you can swear you didn’t know she was Hindu when we turn her in.” He brushes the back of his fingers against my cheek and smiles. “It wouldn’t be so bad to stay here with me now, would it? Just like old times, my little Jazmine.”

I swipe off his hand. “Don’t be absurd, Rahim—I’m not turning her in. Plus, there’s no danger to you—even your servants haven’t seen us. Just show us the back entrance, and the Limbus will never even know we came.”

Rahim shakes his head. “You don’t get it, do you? She’s Hindu. Hindu, don’t you see? All the things I’ve talked about, all the information she now has stored in her brain. A few words from her and the HRM will be targeting my hotel by the end of the day. You know I’ve never had a prejudiced bone in my body, but times are different now, there’s too much at stake.” He shakes his head again. “What in the world possessed you to bring her here? I would never have thought you would endanger me like this.”

“Listen, Rahim—”

“No, you listen. I want you to come with me to her room and act as if nothing’s happened. We’ll go downstairs nice and easy, and you can hand her over yourself to the Limbus to get in their good graces.”

That’s when I pull out the gun. It seems cartoonish, but also quite appropriate, given that the whole situation—the train, the hotel, the nuclear threat—feels like something from a movie script. Rahim senses it too. “What are you now, Jaz Bond? Double-oh-Six, the chhakka secret agent? Shouldn’t you at least butch yourself up a bit?”

“Let’s go get Sarita. Quietly.” I try to sound authoritative, project all my conviction and ruthlessness right through the muzzle of my weapon. But it doesn’t quite work—the gun feels so alien and uncomfortable in my hand I have trouble keeping it level.

“Oh, please. You shouldn’t play with such toys. You know you have no intention of using it. The Limbus will be up in a second if they hear it—even my servants might stop their gossiping for once and come investigate.” Rahim casually pushes my hand away, as if correcting a child. “But I am impressed. You would actually resort to this, just to protect her. What hold does she have? It must be something to do with love, isn’t it?”

I’m loath to reveal anything, unsure I can trust Rahim. On the other hand, there seems little choice but to take the gamble. “That boy you mentioned—the one who went to Delhi. She’s married to him.”

Rahim whistles. “Tell me.”

So the Jazter relates his tale. Rahim is misty-eyed afterwards. “All my life, I’ve waited to care like that for someone. And have him care as much for me.” He smiles ruefully. “I suppose you didn’t know your auntie was so sentimental, such a helpless romantic at heart.”

He tells me the best option might be to take Cadell Road, the main street past the mosque. “They’re going to be on the lookout for you, no matter how I try to throw them off. But it’s bound to be an entertainment night if they’ve captured prisoners from the train—so you might be able to slip through amidst the crowds surging towards the mosque.” He folds my fingers around a roll of money. “The causeway to Bandra is probably too dangerous—you might have to find a boat across. Either way, it’s going to cost.”

“And you won’t get into trouble?”

“With the Limbus? They’re too stupid to figure anything out. And my boss isn’t here, so he’ll never know.”

We hug, and I glimpse an expression of guileless affection on Rahim’s face which takes me back many years. Or perhaps it’s just the light from the table lamp, catching him in such a way to make him look very young. “I hope you find him,” he says.

As I step into the corridor to go get Sarita, he calls after me. “Actually, I did come close to caring a lot for somebody once. But I was only sixteen, and thought it was just a crush.”

INCREDIBLY, MY VISION did come true—Karun and the Jazter ended up living together in our own private flat. Not in Bombay, but Delhi. That’s where Karun returned when he graduated with his bachelor’s, to be closer to his mother, and also pursue a post-graduate degree. Since I received my bachelor of commerce at the same time, I said goodbye to my befuddled parents (“But Mumbai is the financial capital!”) and took up a job at an investment center in Connaught Place.

Our joint apartment almost didn’t come to pass, simply because nobody would rent us one. To head off any reservations, we’d prepared an explanation of wanting to share expenses to save money for when we married. But the sticking factor turned out to be religion rather than two men cohabiting. I’d heard of landlords in Bombay refusing to lease flats to Muslims, but they were ten times more bigoted in Delhi. (“All that terrorism, you know,” one explained rather kindly.) The question of Karun renting a place in his name didn’t arise, students being a category possibly even less welcome than Muslims.

For a while, we lived in a “barsati” in a Muslim section of Old Delhi. Coming from Bombay, I was not familiar with these single-room structures, built as servants’ quarters on house terraces. Ours came with a tiny toilet, a cubicle for bathing, and a hot plate (for which the landlord, Mr. Suleiman, charged us fifty rupees a month for the extra electricity). The place (our “penthouse,” as we called it) had the advantage of complete privacy—only the most determined intruders would climb four floors to barge in on a terrace that baked all day in the heat.

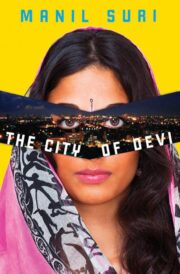

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.