Despite these languorous evenings, our courtship didn’t advance to anything more formal, like a restaurant meal or theater outing. Karun and I did return to Juhu with Uma and Anoop, to test my new aquatic skills in the sea (a “double date,” Uma called it). We chose a Sunday, the most crowded time of the week, when a mass of humanity, dark and roiling, covered the beach. An ongoing battle raged against the sea, which churned at its most ferocious, the monsoon being only a week away.

We abandoned the idea of fighting the crowds and the thundering waves in favor of trying to sneak into the outdoor swimming pool at the Indica. Krishan Patel, a Silicon Valley–returned microchip entrepreneur, had announced the hotel as a grand celebration of India’s triumph in the new world order, an “awe-inspiring homage” that would showcase the entire history and roster of accomplishments of his country of birth. The exterior reflected this—turrets and crenellated parapets evoked Mughal forts and palaces, balconies with lace-like Rajput carvings floated from the sides, and the futuristic glass and steel penthouse suites even sported a few intricately chiseled gopurams, rising above doorways in the Vijaynagar style. The idea of the sari-clad Statue of Liberty replica was to beckon to the West, Patel said, rather than look towards it, India being the new beacon of achievement, of opportunity.

Unfortunately, the opening did not go smoothly. Critics ripped into the fusion of architectural and décor styles (“a schizophrenic monstrosity,” “Shah Jehan goes to the circus,” “more gaudiness and less taste than at a Gujarati wedding”), the computers for the much-hyped laser tribute to desi IT advances kept catching on fire (literally bursting into flame), and a near-riot broke out at the “Stomach of India” restaurant when Jain tourists found a chicken bone in their vegetable biryani. To top it off, Patel had apparently gone bankrupt during construction—rumor had it that the Indica had been bought up and completed by the Chinese.

None of this turned out to matter. The hotel proved such a success that already, an annex was being built in the lot behind. A busy stream of people headed to the pool through the glass doors of the atrium today. Uma strode boldly along, taking Anoop on her arm as well, but the guard challenged Karun and me to produce our guest cards, and we all ended up in the Sensex Bar, drinking coffee.

Although the quotes scrolling along the walls in keeping with the stock market theme were distracting, the tinkle of teacups and pastry tongs helped soothe out the memory of the frenetic throngs on the beach. Anoop droned on about how marvelously his own investments were faring on the Sensex index, giving us a lowdown on the profile of each company he’d picked. How different Karun was from my brother-in-law, I thought—Karun didn’t say much, but I couldn’t bring to mind anyone else in whose presence silence could be so comforting. Afterwards, we stopped to admire the floor-to-ceiling Hussain mural in the lobby, commemorating the Indian invention of the decimal system. An enormous polished metal torus created by a sculptor named Anish Kapoor (who Uma informed us was Indian-born and very famous abroad) floated over us, casting shadows on the floor and walls that looked like skewed zeroes. The chairs, with wide circular rims in keeping with the theme, were also designed by the same sculptor—they reminded me more of wombs than zeroes, and were very uncomfortable (though I didn’t say anything). Uma wanted to check out the Indus Valley theme at 3000 B.C., the disco downstairs, but I imagined standing around in the deafening music, holding five-hundred-rupee lemonades in faux Bronze Age mugs, and declined.

“You could have been brother and sister, the way you two behaved,” Uma said later. “Even two rocks in a museum would generate more sparks. What have you been doing all these evenings after swimming—sitting and staring dumbly like statues at each other?”

“His tongue doesn’t have to fly a mile a minute for me to like him. It’s reassuring to know we enjoy each other’s company enough that we don’t need to stuff each second with inanities.”

“Has he even tried to kiss you yet?”

“We’ve held hands. That’s enough for me.”

“Real hand-holding, or the brother-and-sister variety?”

I didn’t answer. How to make Uma understand the bond I’d discovered with Karun? The matching of our temperaments, the similarity of our history? It was precisely his tentativeness that I found so attractive, the fact that he was as insecure, as uninitiated in romance as I.

“I thought as much,” Uma said, shaking her head. “All this time you’ve spent together, and—nothing? There’s something not quite right.”

“It’s supposed to be the fashion now, I realize, but not everyone can be as brazen as you with Anoop when you were first dating.”

“Well, maybe you should tell that to Mummy. That you’re even more old-fashioned than she is. Do you know she’s been making wedding plans already?—just yesterday she asked if Karun had an uncle or aunt who could be approached with the proposal.” Uma stared thoughtfully at me. “Why don’t you take the initiative yourself, try to kiss him and see?”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

Once articulated, though, Uma’s suggestion persisted in my mind. Why hadn’t Karun tried to kiss me? I had been the first to reach for his hand—could he be again waiting for me to take the lead?

The day it happened, we almost didn’t go to the pool. The air had been turgid with the scent of the monsoon all day, and by evening, there were so many layers of clouds stacked above that the sky seemed to sag under their weight. And yet, no rain fell. As I emerged from the showers, a crack opened up between the crusty edges of two clouds and for an instant, buttery sunlight seeped out.

The pool was almost empty. A group of teenage boys floated about listlessly on the shallow side like bloated seals. The lifeguard ignored the swimmers even more fastidiously than usual—he shuffled around the spectator section, pulling tarpaulins over the wooden benches. “Let’s sneak up the diving tower to catch the view,” I suggested.

The tower had been kept cordoned off ever since a teenager struck his head against one of the platforms on the way down some years back. As we scurried up, our feet left smudged prints on the layers of salt and dirt on the steps. The clouds overhead looked even lower than from the ground, as if climbing a little more would allow us to reach up and poke holes to release the rain. More clouds, darker than the ones above, were massed near the horizon, like cars in a traffic jam, waiting to roll in.

The view from the top was spectacular, the pool having been built right next to the sea. The arms of the city stretched out on either side of us, reaching out to embrace the bay. The water looked neither blue nor gray but some strange and violent color in between, as if plotting to rear up at an opportune moment and swallow the entire shoreline. We leaned on the railing and looked out for the monsoon, a giant ocean liner scheduled to lumber in at any moment.

“I loved the monsoon so much as a child. Baji would take me up to the terrace of our building and we’d wave at the clouds. He said there were people in them watching us, emptying buckets of rain, waving back. When his heart failed, I couldn’t wait for the next monsoon, because I knew he’d be one of the people in the clouds. Even though I was eleven at the time, old enough to realize otherwise. My mother sat there in the tiny terrace shelter and watched me go back and forth in the rain, waving and waving at the clouds. It rained a lot that season, because of all the extra buckets Baji emptied, I thought, to let me know he was all right. It might sound silly, but even now I sometimes feel like waving when I see a rain cloud.”

“Why don’t you?”

“I do, once in a while, when nobody’s watching.” A wave crashed below us, and I resisted the temptation to wipe off a tear of spray on Karun’s cheek. “But one has to let go. One has to grow up and not stay attached to things. That’s what my mother said, especially once her cancer was diagnosed. She told me I could remember her for one year after she died, but then had to put her out of my mind. I think she saw the danger—the way I kept yearning, kept casting around even as an adult, to fill the void after Baji. Once she was gone, she knew the void would only double.”

“Were you very close?”

“It’s strange, but I remember little of her while Baji lived. I know she provided a loving presence, but his intensity overshadowed us all. She only really emerged for me when our perfect triangle collapsed, degenerated into a line. That’s when I began to cloister myself, when I saw her strength, her determination to pull me out of my brooding. Every once in a while, a flash of grief would dart across her face and surprise me—although she absorbed my sorrow, she never shared her own with me. I always thought—hoped, even—that she might find another Baji to inject our lives once more with energy. But to search, you need time, which she didn’t have. Eventually, she had to leave me to my own devices, simply to earn enough for us to eat. By then, I’d learnt to lose myself in my studies, use my reclusion more productively.”

“She sounds like she was very strong.”

“She became that way—fierce, even. I suppose she had to harden herself. She was ferociously determined I be happy in life. And quite ruthless with anyone she considered out to hurt me.”

“Do you suppose she would have liked me?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“My mother likes you too.” It wasn’t quite the symmetrical response, and the awkwardness of articulating it made me blush.

Karun stared silently at the clouds, and I wondered if I had been too forward. When he spoke, he did so haltingly. “I’ve always envied people who know exactly what they want. I sometimes wonder if I could ever be as sure as they seem. If I could experience the feelings I’m supposed to with the same intensity. My mother knew this doubt in me—that’s why she kept urging me to search for a lasting anchor in life. I think she worried that after her, I’d simply drift around, vainly trying to re-create some past ideal.”

My heart started racing. Did his words hold the hint of a hidden invitation? An allusion to the very topic I had been so apprehensive about broaching? I felt as if nearing the conclusion of some game of nerves, like threading the loop over the wire, I had just a short way left to go without making a mistake.

“It’s been over three years since she died—two more than the year she gave me to mourn her. Every night, I can almost hear her whispering into my ear, ‘Settle down now, forget the old. Marry, have a child, build a new trinity.’ I thought it would be a simple matter, but in truth, I haven’t been able to follow through. Even though I’ve been wanting, even though I’ve been lonely. Perhaps it’s a matter of confidence, of being sure one can fulfill the expectations from the other side. Do you know what I mean?”

I didn’t. Was he letting me know, gently, of his disinterest? Declining politely before I posed the question? “Don’t you want to get married?” I found myself asking, more plainly than I would have liked. Then, when Karun didn’t reply, I added, “I do.”

“I know.”

“But you don’t want to,” I murmured, completing the thought for him. A huge weight seemed to lift from me as I said this. The loop had touched the wire, the buzzer had gone off to announce I had lost. The suspense was over, I could breathe in the monsoon air freely.

“It’s not that I don’t. There’s nothing I’d like better than to belong again, be part of my own family. I think I just worry too much about not knowing how things might turn out. Sometimes when you get close to someone, they end up caring for you differently. All the certainty people have—that you have—I wish I could feel the same.”

Was he trying to caution me about something? I couldn’t quite decipher his warning. “One is never completely sure, of course, but one has to try.”

Here was my opportunity, I knew, to follow up on Uma’s advice. I closed my eyes and brought my face to his, guided only by the thought of his lips. When I neared enough to sense his breath, I pressed my mouth quickly to his. Then I withdrew noiselessly, afraid of the bird-like sound my parents made on the rare occasions they kissed. I opened my eyes, but didn’t allow my gaze to climb too high up Karun’s face.

Did my adventurousness put the onus on him to reciprocate? Did he really want to kiss me back, or did he feel obliged, had I embarrassed him into it? I kept my attention focused on the line that first drew me in. It darkened in the middle, then separated in two, then blurred as his mouth drew closer. If there was drama in the universe, it should have started raining at that instant, but it didn’t. There should have been thunder in the background to commemorate the event, lightning to illuminate the instant of contact. I felt the swell of his lips against mine, tasted the salt from the sea on their surface. The wetness behind them felt warm and strangely personal on my tongue. Something in my mind shrank from the idea of sharing saliva, but it was precisely this intimacy—so shocking, so electrifying—that left the muscles in my throat engorged and took away my breath.

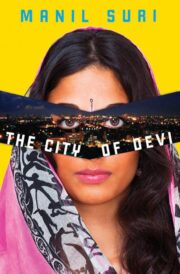

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.