‘Why?’ he’d asked, eyes narrowed. ‘What would be the point of that?’

‘To travel past the prison camp’s Work Zone again.’

Alexei had exhaled sharply through his teeth, a low whistling sound she noticed he made only when caught off guard by a sudden strong emotion. It should have warned her.

‘You see,’ she rushed on, ‘I might be able to find a way to pass a message into the camp. Now we know that these trains carry prisoners in transit as well, I might find a way of contacting one and…’ She slowed the words to make him listen, she knew her brother hated disorder. ‘He might seek out Papa… Jens Friis,… and tell him he might…’

‘That’s a lot of mights.’

She felt a flush rise up her cheeks. ‘You and Popkov might not have success in bribing officials, who might just chuck you both straight into the prison camp instead, leaving me stranded here on my own. That,’ she’d said, snatching her hand away from his arm, ‘might happen. And then what?’

They were standing in the narrow street outside a house whose shutters hung on broken hinges, its roof patched unevenly. Darkness was beginning to roll down the centre of the road in long, strange-shaped shadows, a straggle of horse-drawn carts trundling along behind them.

‘Lydia.’ He did not attempt to retrieve her hand. ‘We must all three of us take care. Listen to me. I cannot do my task here properly if all the time I am looking over my shoulder, worried about what antics you’re getting up to.’

‘Antics?’

‘Call them what you will, but can’t you see that I have to be the one who asks the questions to-’

‘Why? Because you are a man?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s not right.’

‘Right or wrong doesn’t come into it, Lydia. It’s the way it is. You are ranimaya just because you are a woman, and-’

‘What does ranimaya mean?’ She hated asking.

‘It means vulnerable.’

‘Well I think maybe the Communists have got it right.’

He studied her face with such concentration that she almost turned away.

‘And what exactly,’ he asked, ‘do you mean by that?’

‘That Communists give women greater equality, they recognise us as…’

A tiny child, impossible to tell whether girl or boy and with a mop of greasy curls and mucus encrusted under its nose, abruptly materialised at Lydia’s knee. Round, brown eyes stared up at her with the moist hopefulness of a puppy’s, but when she smiled at the child it tottered backwards and stuck a filthy thumb into its mouth.

‘We’re becoming a spectacle,’ Alexei murmured.

He released a long, exasperated sigh which annoyed Lydia, and glanced further along the street to where a man was propped against a windowsill, smoking a pipe. His eyes, behind a pair of spectacles bound together with black tape on the bridge of his nose, were observing them with quiet interest. Alexei took hold of Lydia’s upper arm and tried to propel her forward, but she refused to move. She pulled away from him and squatted down on the pavement in front of the child. From her pocket she extracted a coin, took the grubby hand that wasn’t otherwise occupied into her own, and wrapped the little fingers around the rouble. They felt as cold and slippery as tiny fish.

‘For something to eat,’ she smiled gently.

The child said nothing. But the thumb in the mouth suddenly popped out and ran down Lydia’s hair, past the side of her jaw and on to her neck. It was repeated twice. She wondered if the child expected the strands to be hot like fire. With no sound the curly creature turned and waddled with surprising speed towards an open door three houses away. Lydia rose to her feet and rejoined her brother. Side by side but no longer touching, she and Alexei continued up the street at a brisk pace.

‘If you hand out money to every filthy urchin we stumble over in the streets,’ he muttered, ‘we’ll have none left for ourselves. ’

For a long while they walked on in stiff silence, but just when they passed the park once more, where the wind was still chasing its tail and pursuing the sheets of newspaper, Lydia suddenly snapped, ‘The trouble with you, Alexei, is that you’ve never been poor.’

At the hostel they parted with few words. It was one of the new buildings, deprived of any iron scrollwork, faceless and totally forgettable. Others like it were springing up throughout the town to house the expanding workforce, but it was clean and anonymous which suited them both.

In the entrance hall someone had hung a large mirror, flecked with black age spots like the back of an old man’s hand, and in it Lydia caught sight of her and Alexei’s reflection. It took her by surprise, the image of the two of them. They both looked so… She struggled for the word, abandoned thinking in Russian and settled for so inappropriate. With a jolt she realised they didn’t blend in at all. Alexei was taller than she’d realised and, though his heavy coat was right in every respect and the way his gloves were patched on two fingers was perfect – she suspected he’d purposely torn and then sewn them up himself – nothing else about him fitted in with the dreary little entrance hall. Everything here was plain and utilitarian, whereas Alexei was elaborate and elegant, even when clothed in a drab overcoat. He was like that wrought ironwork outside, carefully crafted and irresistible to the eye.

The thought bothered her. For the first time she wondered if Liev Popkov was right. Alexei could be a danger to them because people noticed him. Yet tonight he was venturing out among the town’s lowlife to start asking questions and she wanted to tell him not to do it. Don’t. You might get hurt.

‘Alexei,’ she said in a low voice, ‘make certain you keep Popkov close by you tonight.’

He raised one eyebrow at her. That was all.

‘You might need him,’ she insisted.

But he took no notice and she knew he was still angry with her about the plan to return to Trovitsk Camp on her own. He was just too damn arrogant to let his little sister tell him what to do. Well, to hell with him. Let him get himself strung up by his thumbs for all she cared. She looked away and once again bumped into her own reflection in the mottled mirror. She swore under her breath.

‘Chyort!’

The girl inside the mirror wasn’t her. Surely it wasn’t. That girl looked utterly dejected, her heart-shaped face thin and nervous. Her eyes were watchful and her hair far too colourful for her own good. Lydia quickly yanked her stupid hat from her pocket, pulled it on even though they were now indoors, and jammed her hair up under it with sharp little jabs that scraped her ears.

‘Alexei,’ she said and found him observing her with that cool scrutiny he was so adept at, ‘if you keep Popkov at your side this evening, I promise I’ll stay shut in my room and not put a foot outside the door until you’re back.’

Would he thank her? Would he appreciate that for once she was offering him peace of mind?

His slow infuriating smile crept up one side of his mouth and for a split second she was foolish enough to think he was going to laugh and accept her offer. Instead the green of his eyes turned a chilly mistrustful greyish shade that reminded her of the Peiho River in Junchow, which could catch you out in the blink of an eye just when you thought it was looking warm and inviting.

‘Lydia,’ he said, so softly no one else would have been able to detect the carefully controlled anger, ‘you’re lying to me.’

She spun on her heel and stalked off down the stubby brown corridor that led to the stairs, her boots clicking on the floorboards. He made her so mad she wanted to spit.

9

Lydia stayed in her room just as she’d promised. She didn’t want to but she did. It wasn’t because she’d given her word – yes, Alexei was right about that: in the past she’d never let something as trivial as a promise cramp her activities – but because Alexei didn’t believe she would. She was determined to prove him wrong.

The room was lugubrious and chilly, but clean. Two narrow single beds were squashed into the small space, but so far no one else had come to claim the second one. With luck it would remain empty. A mirror in an ornate metal frame hung on one wall but Lydia was careful to avoid it this time. Still wearing her hat and coat she paced up and down, fretting at her thoughts the way she’d fretted at the hat earlier.

She tried to concentrate on Alexei, to picture him donning his coat ready for the evening sortie, staring into his own ornate mirror with that look of eagerness, almost wantonness, that sprang into his eyes whenever there was some action in prospect. He always tried to hide it, of course, and she’d seen him disguise it with a yawn or an indifferent flick of his hand through his thick brown hair, as if bored by the world around him. But she knew. She recognised it for what it was.

She paced faster and kicked her foot against the bed frame to drive a jolt of pain up her leg. Anything to keep her thoughts away from Jens Friis. Instead she crammed images of the Commandant’s wife into her brain, of her slender mistreated arms and the graceful swing of the fur coat as she turned her back and walked away along the railway platform.

Walked away. How can you do that? How can you walk away?

A rush of rage swept through Lydia. She wasn’t sure where it came from but it had nothing to do with Antonina. She felt it burn her cheeks and scour her stomach, her fingers seizing one of her coat buttons and twisting so hard it came off. That felt better. She clung to it, trying to sweep away the misery that had driven a spike right through her from the moment she had laid eyes on the prisoners in the Work Zone. The men hauling the wagon over icy boulder-strewn ground, no better than animals. No, worse than animals because animals don’t die of shame. Even from so far away she’d felt it, that shame, and tasted the acid of it in her mouth. And then one of the men had fallen and not risen.

Papa, I need to find you. Please, please, Papa, don’t let it be you crumpled inside that heap of rags.

And suddenly the rage was gone and all she had left were the tears on her cold cheeks.

A knock on the door made Lydia look up. She’d removed her coat and hat and was kneeling beside her bed, engrossed in removing every single item from her canvas bag.

‘Come in,’ she said. ‘Vkhodite.’

The door opened and she expected it to be another overnight resident come to claim the spare bed, but she was wrong. It was Popkov’s friend, the big woman with the straight straw hair, the one from the train, the one with the tongue that asked too many questions. What did he say her name was? Irina? No, Elena, that was it.

‘Dobriy vecher, comrade,’ Lydia said politely. ‘Good evening.’

‘Dobriy vecher. I thought you might be bored here on your own.’

‘No, I’m busy.’

‘So I see.’

The woman didn’t attempt to enter the small room. Instead she leaned a hefty shoulder against the doorframe and continued to smoke the stub of a cigar, balancing it delicately between her fingers. Lydia paused in arranging her possessions neatly on the quilt and studied her visitor.

‘I’m sorry about your son.’

The woman’s face folded into a scowl. ‘Liev talks too much.’

‘Da. He’s a real blabbermouth,’ Lydia said with a straight face.

The woman blinked, then smiled. The aroma of the cigar drifted across the room. ‘Don’t worry, he’s told me nothing that need give you sleepless nights. Just that you’ve travelled from China and are searching for someone.’

‘That’s more than enough. It’s one more fact than I know about you, so I’ll ask you a question.’

‘Sounds fair.’

‘What do you want with Liev Popkov?’

‘What does any woman want with a man?’

She swung her hips lasciviously and pushed the cigar into her mouth, sucking hard on it so that the tip glowed brightly. Lydia looked away. She folded her two skirts, one navy and the other a heavy green wool, and placed them in an orderly pile beside two pairs of rolled-up socks, a pair of scissors, three handkerchiefs, a book and a small cotton drawstring bag.

‘Was your son in the camp?’ she asked without looking up.

‘Yes.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be.’

Something about the way she said it drew Lydia’s glance to her face. It was totally expressionless.

‘He was one of the guards,’ Elena explained in a flat voice. ‘One of the prisoners killed him with a piece of glass. Cut his throat open.’

Lydia’s head filled with the image of blood bursting from the son’s severed flesh, the young man clawing at his throat, eyes glazing. Was Jens there? Did he see it happen? Did he wield the weapon? Because whoever did it would be dead by now. A pain started up in Lydia’s throat. She unfolded and refolded one of the skirts, pulled out a hairbrush from her bag. It wasn’t special to look at, just plain and wooden with a cracked handle, but it had belonged to her mother. She placed it in line with the scissors and drawstring bag.

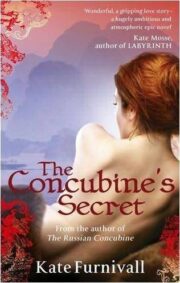

"The Concubine’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Concubine’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Concubine’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.