'Ailith!' His weary features lit with pleasure, but in the next moment sobered as he rose and hastened towards her. 'What are you doing here? Has Goldwin relented?'

'Goldwin is dead.' Ailith felt each word like the slash of a knife. Why couldn't Rolf de Brize have minded his own business instead of forcing her to remain and endure this hell? 'He died at the coronation of your precious Norman Duke.'

'Ah, Ailith, no!'

'Do not touch me!' She took a rapid back-step. 'My husband called you nithing, and if it were not for your wife and the child… and the intervention of Rolf de Brize,' she added with a grimace, 'I would not be here now.'

'Rolf?' Aubert looked more baffled than ever. He rumpled his hand through his unkempt grey curls and rubbed his eyes.

'He says that you have a son in need of a wet nurse?'

'Indeed so. He will die unless we can find a woman to suckle him. Do you know of one?' Aubert looked at her hopefully.

'Yes, I know of one.' Advancing to the bed, Ailith stared down at Felice. The glossy black hair had been neatly braided and arranged, but it only emphasised her pallor.

'She almost bled to death,' Aubert said. 'Even now the nuns are not sure if she will live. Certainly she is unable to feed the baby.'

Ailith could scarcely remember the pangs of her own labour. It was the aftermath that had caused her own mortal wounds. 'I too might have bled to death,' she murmured, touching her bandaged left wrist.

As if aware of Ailith's brooding scrutiny, Felice stirred and licked her lips. Her eyelids fluttered open and then her hand groped for Ailith's.

'I'm so glad you have come,' she whispered. 'I have a son too… born on the eve of the feast of our Lord. Aubert will show him to you. The nuns have put him in a separate room because his crying disturbs me… I am not strong enough to feed him. We have to find a wet nurse.'

Ailith squeezed Felice's narrow fingers. A deluge of words were held back by the sight of Felice's weakness. Ailith could see that even the effort of speech had exhausted her. The new mother's eyelids were drooping and her grip was limp. 'That is why I am here,' Ailith said softly. 'Later, when you are better, I will tell you.'

Felice nodded. 'Tired,' she mumbled and her head lolled on the bolster. 'So tired.'

Ailith gently withdrew her hand and turned to Aubert. 'Take me to the child.'

He led her to a room at the other side of the courtyard. It was warmed by two charcoal braziers and an elderly nun was keeping watch over a cradle containing a swaddled baby while she spun wool. He was asleep, but as Ailith went to the cradle, his small face puckered and he began to grizzle.

'We cannot keep him silent, the poor little scrap,' said the nun. 'He's that hungry, and at this time of year, there is scarcely even cow's milk to be obtained. We managed to buy a jug yesterday, 'but he just sicked most of it up.'

The grizzle became a wail and the wail a full-fledged bawl of indignation. Pain stabbed Ailith's vitals. He was so like Harold, and yet so unlike, a reality instead of a grey little shadow. Her breasts tightened and tingled. Bending over the cradle, she lifted the baby out and sat down on a low stool near the brazier. When she removed her cloak, took the neck pin out of her overgown, and began unlacing the drawstring on her shift, Aubert's eyes widened in startled comprehension.

'Yes,' she said in a voice that was low, but intense with emotion. 'I lost my son too. He was weak from the moment of his birth, and even before that inside my womb, I think. No, do not speak. There is nothing you can say that will be of comfort, and if you offer me your pity, I will hate you.'

Aubert compressed his lips, and after a single look, schooled his shocked expression to neutrality.

Ailith ignored him. The baby demanded her attention. He was dusky-red in the face with frustration and the room echoed to the sound of his screams. The drawstring unlaced, she pulled down her shift and offered the infant her exposed breast. Furiously, Felice's son rooted back and forth, seeking so frantically that several times he missed her nipple altogether. Finally, with some adroit manoeuvring by Ailith, he discovered what he desired. A blissful silence descended, punctuated only by the sucking noises of the baby. Feeling the powerful tug of the small jaws, and the warm weight of him in her arms, Ailith realised how feeble Harold had truly been. Her eyes brimmed, but her tears, although of sorrow, were tears of healing too.

Benedict emptied one breast, belched happily, and demanded to be given the other side too. Rolf was right, he did look like his mother, Ailith thought as she shrugged up one shoulder of her chemise and pulled down the other. His hair was black and he had Felice's feathery eyebrows. His eyes were going to be brown too.

'He is more handsome than you,' she jested to Aubert who had been watching the baby feed with a mixture of relief and apprehension.

'That is not difficult,' Aubert answered with a pained smile. 'Ailith, I know you do not want me to say anything, but I am forever in your debt.'

She shook her head. 'I do not want to talk of debts. It is too complicated to decide what is owed and what is owing.'

The door opened and Rolf strode in. Immediately the size of the room seemed to diminish. 'Has she…" he started to say, then his eyes fell on Ailith and the greedily sucking child. 'Yes she has,' he finished for himself with a satisfied nod.

Ailith felt uncomfortable beneath his scrutiny. The only man to have seen her naked breasts before today was Goldwin. With Aubert it had not seemed so awkward because all his attention had been on watching his son take sustenance. The look in Rolf de Brize's eyes was rather more predatory, and lingered a little too long before he raised it to her face. His colour heightened as he saw the contemptuous awareness in her expression.

'He has taken to it well,' he said.

Ailith nodded stiffly in response. For the moment, because of what had happened at the forge, because of his gaze just now, she could not bring herself to speak to the Norman. He half-turned so that the swollen globe of her breast was no longer in his direct line of vision, and began talking to Aubert.

The baby finished feeding and drowsed in sated, milky pleasure. Ailith gently prised him from her nipple and covered herself, but the act did little to diminish her feeling of vulnerability.

CHAPTER 17

It was a raw day at January's end when Rolf rode into Ulverton at the head of his troop, and was tendered submission by a group of sullen, resentful villagers. Their lord had died fighting the Normans on Hastings field, and with him had perished a third of the young men from the seventy-strong community. Others had returned injured and heartsick. They had no mind to accept a Norman lord, but were forced by their circumstances to do so.

Rolf discovered that the hall had been abandoned after the great battle, and that it had been stripped to a shell. Not so much as a cooking pot or trestle table remained. The English lord had been a widower, with no children to grieve his passing. All that greeted Rolf was the musty smell of a place several months dead. The floor rushes were dank and mouldy, and near the hearth where the lord's seat should have proclaimed its owner's status, there were bits of bone and fruit stones from feasts long gone. On the wall, outlined in white against the grey of old limewash, was the space where a battle axe had hung until recently. Rolf imagined his own weapon sitting there, and snorted at the irony of placing an English war axe amidst such squalor.

Yet, despite the shortcomings, he was pleased with his new estates, of which Ulverton was the main settlement. They were easily as large as Brize-sur-Risle and had just as much, if not more potential. The lands were situated on the south coast of England, five days' ride from London, and included several fishing villages and a fine, ocean-going harbour along the shingle shoreline. There was excellent grazing for his horses, as well as for the large population of sheep which the rich downland supported. Rolf recognised the value of the limestone soil for producing sound bones in the animals he intended to breed here.

In the time of King Edward, Ulverton had been wealthy, and the difficulties that Rolf encountered were only recent and certainly reversible. He threw himself into the task with determination. The hall was patched up to make it habitable while he set about finding a site on which to build his keep. He soon chose a fine slope overlooking the village and backed by high sea cliffs. The villagers were none too happy at having to dig the mounds and ditches of the castle, but had little choice except to comply. Besides, they frequently heard tales from other communities about the harshness of the new Norman masters, and could only be thankful that their own, while not being Saxon and therefore of considerably less calibre than the former lord, was neither unfair nor tyrannical in his dealings with them. Indeed, he permitted them to retain their old laws and customs with very little interference.

Ulverton settled down to a state of truce. The castle mound continued to grow, and with it grew the relationship between the people and their new lord. He looked more Norse than French, they said, and unlike the other Normans over the hill, he spoke some English and strove to learn more at every opportunity.

Rolf treated his new peasants in much the same manner as he treated those on his Norman lands. He was of the opinion that to obtain the best from any tool, be it a spade, a piece of harness, a horse or a man, you had to treat it well. Oil and polish, kind words and discipline, a listening ear. It was not altruism, but self-interest that motivated him.

In March, King William announced his intention of returning to Normandy to parade his English victory throughout his duchy, and Rolf felt secure enough in his position at Ulverton to leave the lands in the charge of a deputy and make the journey too. But first he travelled to London, to the house of Aubert the wine merchant in order to pay his respects to the family: to Felice who had only just been rising from a protracted childbed when he went to claim his lands, to the thriving, rosy-cheeked baby to whom he had the serious honour of being Godfather, and to Benedict's wet nurse… Ailith.

Ailith sat in a puddle of sunshine, carding the last of the previous year's fleece ready for spinning. The day was so mild that she was beginning to believe that spring was actually on the threshold. There were often black days in her existence when she felt so full of grief and anger that she did not care about the weather or any other circumstance of her life, but today was a good one. She could feel the sun's warmth in her bones, and appreciate the comfort with which she was surrounded.

For a month, before coming to live in Aubert's house, she had dwelt at St Aethelburga's while Felice slowly regained her strength; a month in which her own wounds had begun to heal. On her second day at the convent, Rolf de Brize had taken her to witness the burial of Goldwin and Harold within the same grave. Although she was but recently out of childbed and not allowed within the hallowed confines of a church, still she was permitted to stand at the graveside. That had been one of the black days. She remembered it patchily, but the most disturbing part was her vivid recall of the Norman's strong, wiry grip holding her steady at the graveside, preventing her from falling in as the labourers began shovelling earth back into the hole.

Ailith liked Rolf de Brize, but she preferred to keep her distance. There had been an incident at the end of January just before he left when she had sought him in Aubert's stables to say that food was ready, and discovered that he had not heard the dinner horn because his face was buried in the ample bosom of Gytha the Alewife from down the road. Ailith had backed away quietly before either of them saw her, and had informed the household that Rolf was busy and would eat later. A whole candle notch later as it happened, his lids heavy with satiation. His appetite had been enormous – he had devoured all the chicken stew which Ailith had set down before him, and more bread than herself, Felice and Aubert put together.

'Ailith said you were busy in the stables,' Felice had told him.

Rolf had looked sharply at Ailith, and then a slow, incorrigible smile had spread across his face as hers reddened. 'I was,' he had replied without elaboration. No, he was neither to be trusted nor encouraged.

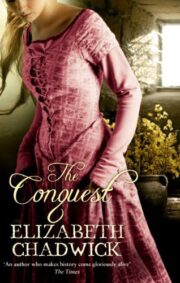

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.