They approached the village on a hazy spring afternoon, the sun a misty halo in a pale sky. The track was muddy and Rolf was encouraged to see the print of hoof and foot gouged in the mire. Neither pigs nor swineherd materialised to greet them, and at the place where the Odin statue had stood sentinel, there was nothing but a lush growth of nettles. Rolf drew rein and saluted his respect as if at a grave before riding on.

The palisade of wooden stakes was commemorated by a charred circle of ashes, blurring black into the soil. It surrounded fewer than a dozen houses, and these were new structures of fresh thatch and green timber. More black smears and twisted black beams revealed what had happened to the other dwellings. Ulf's village had not escaped the attentions of William's Norman mercenaries. It had been seriously mauled, but it had not been utterly destroyed.

A woman carrying a large water jug from the well was the first person they encountered. Her eyes widened, but she did not panic as the swineherd had once done. Instead she put down the jar and went straight into one of the huts, her step swift but graceful. Rolf recognised Inga, Ulf's daughter-in-law. Moments later Ulf himself emerged from the building. He walked with a stick, his limp severe, but the same iron will was in evidence.

Rolf dismounted and walked over to him.

'So,' Ulf jutted his silver and rust jaw at Rolf, 'your Viking instinct brings you back to see what the ravens have wreaked?'

Rolf drew a deep breath. 'I am grieved for what my countrymen have done, but I tried to warn you what would happen.'

'Aye, so you did,' Ulf said without warmth. 'What do you want?'

'If you still have ponies, I have come to trade for another stallion. The one you sold me broke his leg before he had covered more than one season of mares.'

'Aye, I still have ponies.'

'Will you trade?'

Ulf stared at him for a long time with eyes of winter ice. Then abruptly he swept his arm towards his hut. His tunic sleeve fell away to reveal heavy bracelets of incised silver and bronze on his wrists. 'Enter within and partake of what meagre hospitality I can offer. I am one of the fortunate ones, I still have a roof over my head.'

Once more Inga brought food for the guests, serving Rolf and his men coldly, her mouth tucked in a severe fold and her cat-hazel eyes downcast. The bread was gritty and impure, the boiled stockfish salty and tough. Mauger pulled a face and almost gagged, but a glare from Rolf made him choke down his food and murmur his thanks.

'Your community has survived,' Rolf said, forcing himself to eat, knowing what a sacrifice the old man was making in his pride.

'After a fashion,' Ulf growled. 'There are no villages left hereabouts with whom we can trade. We have to go to York for our provisions and that costs silver. But it is due to you that some of us are alive to grumble about our lot.'

'Due to me?'

'As you said earlier, you warned us about what your Duke would do. I heeded your words above those of my own son and I had our people take all of our winter supplies and animals into the woods and hide them. When the Normans arrived, they found the village already deserted. All they had to burn were our empty houses.'

Rolf ate in silence. There was nothing he could say apart from that he was sorry. He was being thanked and hated at the same time, and the sensation was disquieting. His eye fell on Inga as she went about her duties. She looked beaten down and weary. Her son sat on the floor playing with a chicken's foot, fiddling with the guiders to make the toes move. Of the little girl there was no sign. 'There were many more houses when I came before,' he said to Ulf.

'My son Beorn and our hot-headed young men died fighting a Norman patrol on the York road at the beginning of the troubles. And then, around the time that we had to hide in the woods, many of us took sick of a pestilence and very few recovered. Inga's daughter was among them.'

'I am sorry.' Rolf's glance flickered again to the young woman. He would have pitied her, but her self-contained manner forbade such a sentiment.

'Being sorry will not bring the heart back to this place,' Ulf grunted sourly. 'Have you finished? Then come, I will show you the ponies.'

The new stallion was a glossy, pine-pitch brown which hovered just short of being pure black. He was more sturdily made than the previous bay Rolf had purchased, for he was three years older and in his prime. Fine hairs feathered his hocks and pasterns, but his leg action was high and clean.

'I was saving him for myself,' Ulf announced, 'but there is no-one in this wilderness with the money or need to buy a horse unless it be to eat, and for that they will steal. I keep him close to the compound; I know if I do not, he will finish his life upon some poor wretch's table. Silver is of more use to me now. I can buy seeds and supplies to start anew.'

They settled down to haggle a price, although Rolf did not haggle very hard, for he could see the older man's need. Blood money, he thought, the price of feeling less guilty for the sin of being a Norman.

'There is one other thing I desire of you,' Ulf said as Rolf counted the silver coins out of his pouch.

'There is?' Rolf was alerted to caution by the sudden gruff note in the other's voice.

'When you leave, I desire you to take Inga and the lad with you. There is no future for them in this village save that it be from hand-to-mouth.'

Rolf stopped counting and looked at Ulf in surprise. 'You would entrust them to a Norman?'

'To save them from being killed by other Normans. What if your king's mercenaries should return and ravage again?' Ulf shook his head, his shoulders drooping. 'Even if that does not happen, Normans will still come and lay claim to what is ours, and we are too weak to stop them. What was "Ulf's land" will become Osbert's or Ogier's.' He spat the French names with contempt. 'How will my grandson fare against them, do you think?'

'You believe they will fare better in the south?'

'They could not fare worse,' Ulf said scathingly, but then moderated his voice. 'You are a man of honour, I trust you to see them safely settled.'

Rolf looked thoughtfully at the old horse-trader. 'And what will you do?'

'I do not need a place of sanctuary. My roots are too deeply buried here to be torn up and planted elsewhere, and there are others in the village of my ilk who will need my counsel in the months to come. For Inga and Sweyn it is different. The boy is still thistledown in the wind. He could settle anywhere.'

Rolf inclined his head. 'Then so be it,' he said. 'My roof is theirs.'

Inga perched silently on the baggage wain, her posture resembling a drawn purse concealing its contents. Her arms were folded across her breasts, hugging a thick, rectangular cloak to her body. Her fists were clenched, her mouth was pulled tight, and barely a word had she spoken during all the long first day of the journey towards Ulverton. Her son, Sweyn, by contrast, was riding with Mauger and talking nineteen to the dozen, his eyes bright with the joy of adventure. Rolf harboured no qualms about him settling to a new life. His mother, however, was cause for concern.

He rode up to the front of the wain where she was huddled beside the driver, her expression remote and enigmatic. Her bones were more dainty and precise than Ailith's, her beauty more exotic than Arlette's. Her coldness piqued and intrigued him. He rode closer, intending to speak to her, but a loud honking and a clattering of imprisoned wings caused his mount to shy, and he spent several precarious moments preventing himself from being thrown.

Inga had insisted upon bringing her geese to Ulverton, or at least the means to begin a new flock from the original birds. They would be her livelihood, she said. No-one could smoke gooseflesh as succulently as she did. They would provide her with an income and they would be a reminder of home.

Much of the disturbance was caused by an aggressive young gander, still in the brown plumage of adolescence. He had been hissing threats ever since being latched inside his wicker cage at the journey's outset. Rolf eyed the bird with disfavour and hoped that it would soon be consigned to the smokehouse.

Inga regarded him coldly as if she could read his thoughts. 'I chose the strongest,' she said, 'because only the strong survive.' The words held a note of challenge.

Rolf inclined his head. 'Then you must be strong too,' he said.

'And my husband was weak?'

'He was faced by men more ruthless.'

'Hah,' she said with scornful dismissal and looked away. 'He was worth ten Normans, my Beorn.'

The goose beat its wings against the wicker bars and continued to threaten Rolf and his mount. The horse sweated and pranced, thoroughly upset. 'He's worth nothing now that he's dead,' Rolf replied, stung by her contempt, and he rode off to join his men.

CHAPTER 31

AUTUMN 1075

On the day that Julitta fell in love with Benedict de Remy, she was five years old and playing a game of pretend. It was early autumn, the leaves gowning the trees in tints of tawny, amber and flame. Ulverton's razor-backed swine rooted in the moist ground beneath the canopy for a pannage of acorns and beech mast, and the villagers gathered firewood against the harsher months to come.

Julitta had slipped away from her mother and Wulfhild who had been too busy and harassed preparing a feast to notice her absence. The de Remy's were expected from London, and all had to be made ready for their arrival. Julitta hoped they would come soon. She liked Aubert; he had a face like a hoary tree trunk, with deep smile lines either side of his mouth. Aunt Felice, as she respectfully called his wife, was beautiful. She always wore lovely clothes and she smelled delicious — of roses and spice. They had a son, a big boy of nine years old, named Benedict, and sometimes he would play with her.

This particular morning, Julitta had sneaked some hazel nuts from one of the bowls laid out for the feast and had dropped them into the small draw-cord purse attached to her belt. Her father would sometimes ruffle her tangled dark auburn curls and call her a squirrel because of her delight in hoarding small objects in unexpected corners — marbles, feathers, little coloured stones. Today, Julitta had decided to be that squirrel.

The autumn gold of the trees beckoned and the nuts in her pouch were to be her food.

The tree she chose was a young oak growing beyond the castle ditch close to one of the dew ponds. The prevailing winds had caused it to lean to one side, and its tilt had been further exaggerated by the attentions of sheep and cattle using it as a scratching post. There was a branch at just the right height for the reach of Julitta's legs, and in no time at all, she had pulled herself onto it. The next branch was a little further away, but after a determined struggle and a scraped knee, she succeeded in reaching it. She sucked the graze, tasting the saltiness of damaged skin, and having reassured herself that the injury was not great, she sought for the next hand- and foothold. She was a quicksilver squirrel, whisking her way through the branches, her long red hair, a busy tail.

Light although she was, her progress dislodged amber showers of leaves. A thrush which had been roosting in the oak took wing in twittering alarm. Julitta discovered a nest which had been well used during the spring and summer. It was comfortably rounded into the shape of a bird's breast and from somewhere the former occupant had filched some bright red embroidery wool and used it for part of the lining. Julitta was captivated and gently dislodged the nest from its position in the fork of two branches. Perhaps her mother would let her keep it.

She settled herself against the rough main trunk, wriggling back and forth until she was comfortable, and then removed one of the nuts from the pouch. Her teeth were too small to pierce the glossy brown shell. She tried striking the hazel on the tree trunk, but her blows were not strong enough, and finally she just had to pretend to eat the nut. She was not really hungry anyway, having devoured bread, honey and a beakerful of buttermilk whilst sitting on her father's knee before he rode out to inspect his horses. Frequently he would take her with him, but today he had being too busy, and Julitta felt secure enough in his love to let him go without too much protest. There was always tomorrow.

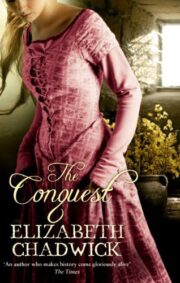

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.