It was the middle of the afternoon when Benedict arrived at Ulverton. The late May sun dazzled on the sea and clothed the new green of the land with an eye-aching intensity. On the castle's outer defences, a group of labourers were digging foundations for a stone curtain wall to replace the wooden palisade. They worked bare-chested, their skins reddening beneath the first onslaught of the sun that year. The chink of their spades and mattocks, their salty language, followed Benedict through the gates and into the sun-basked lower bailey.

His dürsty horses were eager to plunge their muzzles into the stone water trough. He let them drink, but only for a short time as a precaution against the colic. A groom came over to take them in hand.

'Is Lord Rolf here?'

The groom fixed his gaze on a point beyond Benedict's shoulder. 'No, sir,' he said and quickly lowered his eyes.

Turning, Benedict found himself facing Gisele, his betrothed. Their wedding was set for the autumn, her mother having finally decided that at nineteen years old, her daughter was robust and mature enough for child-bearing. 'My father is riding by the shore,' she said. 'Do you want to-come within?'

Gisele was attractive to look upon, being tall and slender with fine, silvery-brown hair and clear grey eyes. Her nose was dainty and sharp, her cheekbones high. Her mouth was small with a tendency to purse when she thought she was being put upon, or when, like her mother, she was judging others and finding them lacking. Benedict had been graciously permitted to kiss that mouth once or twice and had made his own judgements. He did not attempt to kiss it now, not in public before the groom.

'No, I have to see him, it's urgent. But if you could bring a cup of cider out?'

She nodded and started to turn away, but not before he had seen the curiosity in her eyes. 'I can't tell you,' he said. 'Not until I've spoken to your father.'

Alarm joined the curiosity. Ignoring it, he swung to the groom and commanded him to saddle up Cylu the grey. By the time Gisele returned, Benedict had stripped his cloak and tunic and was already astride the fresh horse. Leaning down, he accepted the brimming cup from her hands and downed the contents in a few fluid swallows of his strong, young throat. The taste was acid and clean, clearing the dust from his mouth, stinging slightly in his nostrils.

'That's better,' he said gratefully and handed the empty cup back down to her.

Although Gisele smiled at him, it was with a closed mouth and he saw her nose wrinkle fastidiously. He was immediately aware of the stale condition of his garments – five days on his body without a change, and since the episode in the bathtub at Southwark, he had washed nothing more than his hands and face. The horse swung its head, hooves dancing eagerly. Flecks of foam spattered from the bit. Gisele trod hastily backwards before her immaculate blue linen gown could be smirched.

'While you're gone, I will have the maids prepare a tub,' she announced. Although she was looking at him through her lashes, the glance was far from provocative; her lips were pursed. And when he did step into the tub, he knew that the proprieties would be rigidly observed. No taking liberties until the nuptial knot was securely tied, and probably not even then, he acknowledged wryly. Still, the thought of a warm tub and fresh raiment was fortifying, and he smiled his gratitude at her before turning the horse.

Cylu was fresh and responded to the touch of his heels with a half-buck and an exuberant breaking of wind. The slight wrinkling of Gisele's nose became an outright grimace of distaste and sent her in full retreat back to the hall. Grinning, Benedict patted the muscular, glossy neck, and urged the horse to a pacing trot.

Rolf was riding Cylu's sire, Sleipnir, along the path which led between Ulverton and one of the small fishing communities beholden to the main village. Benedict, having enquired first of the miller and then the reeve, caught up with him on the dark stone cliffs, negotiating the track which meandered down to the sand and shingle beach. Some of the downland was cultivated with maslin, the green shoots of wheat and rye rippling in the warm wind blowing off the sea. Gulls wheeled and spiralled, and a white-tailed eagle soared on spread pinions. Sheep grazed the clovery turf, watched over by an elderly man, his weathered faced tanned a deep soil-brown.

Rolf looked over his shoulder and reined to a halt. 'I thought that I heard hoofbeats,' he said, and having looked Benedict up and down, his eyes narrowed. 'Is there a reason for such haste?'

There was just room for two horses to ride abreast on the track and Benedict joined his lord. The sun was bright on the older man's face, emphasising the deep creases at the eye corners and between nostril and mouth. Threads of silver were beginning to dim the garnet brightness of his hair, but enough fire remained to reveal from whence Julitta had inherited her colouring. 'Sir, there is indeed,' Benedict replied, and wondered how he was going to tell Rolf what had happened in London, that the woman and child over whom he had long grieved were resurrected. There was no easy way.

'Well, what is it, spit it out!' Rolf snapped impatiently as Benedict hesitated. 'If you've bought a sow instead of a mare at Smithfield, or sold those nags I entrusted you at a loss, you might as well say so.'

'No, sir, I fared excellently at the horse fair.' Benedict deliberated a moment longer, and as they reached the flat ground of the sandy path behind the beach, inhaled deeply. 'You must come to London immediately. Lady Ailith and your daughter are at my parents' house near Dowgate, and Lady Ailith is grievously ill with the lung sickness.'

The horses continued to pace forward, tossing their heads towards each other, swishing their tails against the flies. Rolf's hands were relaxed on his mount's bridle and his face was expressionless.

'Sir, I…' Benedict stuttered with a degree of alarm.

'I heard you,' Rolf answered shortly. His eyes were fixed on the silver forelock between Sleipnir's ears, but without focus. 'By grievously ill, I suppose you mean dying?'

'Yes, sir.'

Silence again. They came to half a dozen fishermen's houses beyond the high tide mark, and the hulls of two small boats upturned on the shingle. Out at sea, Benedict's keen eye could just pick out the masts of three fishing craft. The houses were deserted, for the womenfolk were out in the fields tending the crops. Rolf drew rein and stared at Benedict, forcing him to hold eye to eye when the young man would rather have looked away. 'How came they to your father's house?' he demanded. 'Tell me.'

Benedict searched his mind to pick out what could be told and what was better left unsaid. 'Mauger and I were looking for…' he began.

'I will have the truth,' Rolf interrupted harshly. 'Do you think I have not learned how to live with it these eight barren years? Do not presume to pity me, boy, or judge what is and is not fit for me to hear.'

Benedict felt himself redden beneath Rolf's fierce green stare. The ability to read the faces and almost imperceptible body gestures of other men was a great advantage and Benedict had done his best to learn from Rolf. But he would never be able to flip the coin onto its other side and dissemble with ease.

Trepidation in his eyes, he began again, but out of pride, made sure to use the same opening words. 'Mauger and I were looking for a boat to row us across the river from the Southwark side…'

As his tale progressed, Rolf's set expression grew ever more rigid until his face might have been carved of stone. Only once did he move, and that was to steady the horse by taking a firmer grip on the reins.

'Wulfstan is dead,' Benedict added when he had finished the tale. 'Of a seizure at home, so the rumour goes. Already his family has moved to disguise what really happened. On my way out of the city I was stopped twice and told the news by people who knew that he and my parents were acquainted.'

Rolf neither moved nor spoke and Benedict grew concerned. 'Sir, shall I…?'

He saw Rolf make the effort to tug free of the immobility of shock. 'Leave me alone awhile to think,' the older man said, his voice slow and careful, as if he were treading in deep water and feeling for each footstep. 'Return to the keep and tell the women not to wait dinner on me.'

'Shall I tell them anything else, sir?'

'No.' Rolf shook his head. 'I will tell them myself.' He tugged on the reins and the grey stallion turned. Out to sea the fishing boats were closer now. Benedict could see the men on deck and the dark shape of a net draped over the side of the nearest craft. He hesitated for a moment, watching the boats, inhaling the warm salt wind, and feeling totally out of his depth. With a final, worried glance at Rolf's solitary form, he kicked Cylu in the direction of the keep.

A series of mental visions spilled like blood from an opened vein as Rolf rode the old stallion along the beach. He saw Sleipnir trotting towards him, ears pricked and tail carried high, Ailith in pursuit, a birch besom brandished in her fist. He saw her in the forge, a knife poised to take her own life, and he watched himself wrestle that knife out of her hand and cast it across the room. Instead of the swift mercy of the blade, he had given her the long, slow death of loving him. And then he had turned that knife on himself and twisted it deep.

The horizon was suddenly blurred. He dashed his sleeve across his eyes and swallowed. He saw her feeding Benedict, her blonde braid heavy in the firelight, watched her furiously pummelling a tub of laundry while he asked her to become chatelaine of Ulverton. That first, frozen moonlit kiss that dissolved into molten urgency, searing them both to the bone. Her hair spread upon the pillow, grasped in his hands; the beauty of her strong, generous body which had given him such pleasure to possess and had bestowed on him the gift of a fire-haired child. He wiped his eyes again, but his vision blurred almost immediately. Ailith and Julitta eking a living in the stews of Southwark. Eight years. He had thought in his stupidity that even if he had not found peace, he had at least discovered a degree of equilibrium, but he had been deluding himself. He had discovered nothing, and still had so much left to lose.

He could ride no further. Halting Sleipnir, he dismounted, and seating himself on a flat, sun-warmed rock, put his head in his hands.

'A bathhouse?' Arlette's shocked gaze flickered rapidly from Rolf to Gisele, as if worrying that the very mention of the word would corrupt her daughter's purity. 'What were they doing in a bathhouse, or perhaps I should not ask?'

Benedict, who had been invited to share in the discussion that was taking place in Arlette and Rolf's bedchamber, cleared his throat. 'Not all bathhouses are dens of iniquity,' he defended, thereby earning himself a glare from his future mother-in-law, and a prim lip-purse from Gisele. 'Besides,' he added doggedly, 'from what Julitta told me, her mother was the housekeeper of the place, they were never actually involved in the private bathing of the clients.'

Arlette sniffed scornfully. 'That is as maybe,' she said. 'And it is only Christian charity to pity the woman and the child. But what is to be done with them? You say that the mother is dying of the lung sickness? Aye well, perhaps that is a blessing in disguise. But the girl…'

'My daughter,' Rolf interrupted, his voice almost a snarl, a dangerous glitter in his eyes. 'Julitta is my child as much as Gisele. Bridle your tongue when you speak, or by God I will do it for you.'

Arlette paled. 'I was only going to say that you need to take careful thought for the girl's welfare. She has known such an uncertain life, that there are bound to be difficulties.'

Rolf's eyes remained suspiciously narrowed, but he leaned back in his chair and slowly rubbed his forefinger back and forth across his upper lip while he considered her words.

Benedict glanced around the family and tried to imagine Julitta settling into the household. From what he remembered of Julitta the child, and from what he had seen of Julitta the budding woman, there was going to be precious little peace in the bower. Just the sight of Julitta's wild red hair would be enough to send Arlette running for her shears and a thick linen wimple to tame and cover such wanton glory.

'I am more than willing to take her under my wing, indeed I am,' Arlette added piously.

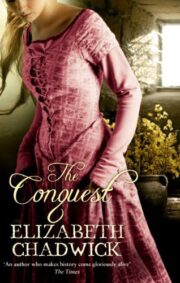

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.