'The dangers of the mountain roads, my advancing years,' Sancho said with a cackle of amusement. 'Let me tell you, I've been as far as the cities of Constantinople and Nicaea in my time in search of bloodstock. I have travelled throughout Andalusia and the Moorish kingdoms.'

'But that was long ago.' Benedict looked at the wizened, leathery face across from him, the milky eye and scrawny throat.

'Not that long. Even at my time of life, a man can still have itchy feet. Besides,' he added, 'there is no need to cross the mountains. Galleys are easily hired in Corunna to make the journey up the coast. There's a huge horse fair in Bordeaux before the summer's end and I want to do some trading. In previous years I've sent younger men, but I don't see why I shouldn't indulge myself one last time.'

'It might well be your last time,' Benedict could not help but say. And yet the thought of the old man's company was comforting, and there was no conviction in his protest.

Sancho shrugged and smiled. 'It is my choice.' He gestured at the merels board. 'Your move.'

CHAPTER 58

The Draca, one of Aubert's wine vessels, docked in Bordeaux, having sailed down the French coast from Rouen. The late summer journey had been beset by unseasonable winds and some minor squalls. Mauger, never a good ocean traveller even in the calmest of conditions, spent a great length of time leaning over the gunwale, his complexion a delicate shade of green.

Julitta, in contrast, revelled in the brisk weather and the freedom from being tied to the quiet domesticity of Fauville. She took up a favourite position on the raised decking by the prow, and stood for hours on end, watching the Draca carve her way through the glistening green waves with their white netting of foam. If conditions grew too rough and she found herself becoming saturated by the spume, she would retire to one of the benches in the hold which lay amidships, and keep Aubert's cargo company. He was exporting barrels of English mead, and hoped to bring home a cargo of leather and strong southern wine. Not that he was personally on board the vessel, but one of his senior overseers was – a black-bearded, hearty soul named Beltran who had been sailing these waters for the better part of twenty years.

Beltran took Julitta and Mauger to the lodging house where he himself usually stayed when he was in Bordeaux and within moments secured them a bed for the night and the promise of a substantial meal. At the mention of food, Mauger compressed his lips and excused himself, declaring that all he wanted was a bed that did not move.

Beltran and Julitta exchanged amused, pitying glances, and guided by their landlady, a talkative, tiny woman with sallow skin and beady black eyes, they descended from the sleeping loft and entered the main room below.

Gulls screamed overhead. The sounds of the bustling, dusty streets percolated through the cool stone walls, which kept out the worst of the day's burning heat. Their hostess brought them a jug of wine, a loaf, and earthenware bowls of steaming fish soup. 'Are you on a pilgrimage?' she asked curiously as she set the food down on the trestle.

Julitta shook her head. 'We are here to buy horses at the fair.'

'Ah.' The woman absorbed the information, and if anything, her curiosity increased. 'I think you are newly married then? He does not leave you at home with your children?'

Julitta half-smiled a response and curbed the impulse to tell the woman it was none of her business. Let her believe that this as a journey undertaken by an ardent groom and his new bride.

'You should travel down to Compostella,' advised their hostess. 'Ask his blessing.' She patted her belly, her meaning obvious.

Julitta reddened. At Dame Agatha's she had learned how to protect herself against the fate of pregnancy. Merielle, in one of her rare spurts of benevolence, had shown her the method employed by the cannier whores. You took a small piece of moss or sponge, soaked it in vinegar, and inserted it into your passage. So far the method had worked remarkably well and Julitta desired no intervention from St James.

'Me, I have eight sons, and twenty-four grandchildren,' the woman declared proudly, and proceeded to regale Julitta with all their names and circumstances. Julitta ate her soup, which was delicious, and tried to look interested. She was aware of Beltran's amusement and wondered why on earth he chose to lodge here. He did not strike her as a man who liked having his ears talked off, even for the sake of good cooking.

Finally the garrulous old biddy removed their dishes to rinse them out by her well in the yard. Julitta wondered which was worse, retreating to lie down in bed beside Mauger, or remaining here to be verbally assaulted by her landlady.

'How far is the horse fair?' she asked.

Beltran's lips twitched. He wiped his palm across his bushy moustache and beard. 'Not far,' he said.

They left the lodging house, and walked along the banks of the Garonne. Numerous trading galleys were moored along the wharves and the vinegary smell of split wine casks pervaded the air, reminding Julitta of the time spent at Aubert's house in London.

'Clothilde means well,' Beltran said. 'Usually she gives lodging to ships' masters and the like. It is not often that she plays host to another woman.'

Small wonder, Julitta was tempted to say, but she managed to curb her tongue.

They walked past other moored vessels, including Italian and Byzantine horse transports. At one of them, she saw a small, leathery old man guiding a mare and colt down a ramp. He issued orders in rapid Castilian Spanish to a groom. From between his clamped lips there protruded a stick of liquorice root.

'Iberian horses,' said Beltran. 'Your husband will be spoiled for choice.'

Julitta admired the mare and foal and stepped forward for a closer look. The man with the liquorice root swivelled milky eyes in her direction and looked her up and down. His stare was disconcerting, for although he looked blind, Julitta could tell that he saw her perfectly well.

'They are fine horses,' she said to him.

'Aye, that they are, my lady.' His tone was dour.

'Are they to be sold at the fair?'

'No, they're already spoken for —just resting them a couple of days before we sail on.'

'Do you have others?'

'Already taken to the market place.' He gave a nod of dismissal, spat a wad of black saliva at his feet, and recommenced talking to the groom as if Julitta did not exist.

That was the drawback with Spanish horses, Julitta thought. They were so much in demand that those who sold them could be as objectionable as they liked and still reap a profit. Even if she told this particular trader that her husband was commissioned to purchase a horse for Duke Robert of Normandy, she doubted that it would increase the level of his courtesy.

Julitta moved on. A glance over her shoulder for a final look at the mare and foal caught the small trader in the act of staring after her and Beltran, a thoughtful look on his wizened features.

The horse-dealer's name was Pierre, and he dealt in war stallions, brood mares and endurance horses for distance travelling and the hunt. He was the last in a long line of dealers visited by Mauger and Julitta that morning. It was close on noontide now, the sun high and hot. Mauger wore a frown, and his eyes were heavy. He was still suffering from the aftermath of the sea journey, and the red heat of the sun, the dust and the market place smells, had all combined to give him a nauseous headache.

He had never looked at so many horses and discovered so many nags. The southern lands might be famous for their bloodstock, but he had seen precious little so far. Scrubby ponies, cow-heeled knock-kneed jades, broken-winded hacks; the parade had been endless, yet he had seen nothing to suit the tastes of Duke Robert of Normandy. The problem with looking for gold was sifting through the dross to find it.

Pierre was short and stocky, of a similar build to Mauger, but larger and softer in the gut. He had curly blue-black hair and the skin of his face was deeply pitted. Shrewd black eyes assessed his potential customers and he spread his hands towards his merchandise. 'You want warhorses?' he enquired. 'You have come to the right place.'

Julitta had heard that opening gambit several times and was not impressed; however, she kept her eyes modestly downcast and hung back a little. Pierre flashed her an assessing glance as if considering the points of a young mare ripe to be serviced.

'I will be the judge of that,' Mauger said tersely. 'Let me see what you have.'

Pierre shrugged and smiled with his mouth but not his eyes, and gestured his groom to bring forward a cream-coloured stallion.

Mauger began an examination, running his hands lightly over the horse in search of lumps and defects. He looked in its mouth, discovered that it was around eleven years old, and shook his head. A younger animal was brought forth, a skittish bay with black points. Julitta went to cast her eye over the rest of Pierre's stock. Some animals were quite presentable, but there was nothing better than what they had at Brize or Ulverton.

Her eye was caught by a dappled grey courser standing quietly at the end of the line. It was a little short of fifteen hands high, its mane and tail pure silver against the smoky grey rings of its hide. Beside it stood a smaller, chestnut mare with a white star marking on her forehead and a white sock on her offside hind leg. Julitta admired the two horses, thinking that they were the best she had seen thus far, although sadly neither was of the type to turn into a destrier. They looked extremely like her father's horses, she thought, the mare from Brize, the gelding from the grey herds at Ulverton. Suddenly, despite the heat of the day she was cold.

'Cylu,' she said softly and approached the grey.

Immediately he turned his head, and with ears pricked, nickered to her. Julitta's stomach plummeted. She had expected the horse not to respond, or to turn a different face towards her, but there was no mistaking the small coronet of hair on Cylu's forehead that grew against the grain, nor the pink splash on his otherwise dark grey muzzle.

She compressed her lips, feeling sick. Pierre's groom gave her an anxious look. 'My lady?' he questioned. 'There is something wrong?'

'That grey horse, where did your master buy him?'

The groom shrugged. 'Master Pierre bought him and the mare from a Basque trader last week. Do you like him?' He smiled and patted Cylu's smooth dappled neck. 'A fine riding horse, and still young.'

Julitta would not have called ten years old still young, but the groom's small lie was swamped by the greater tide rising in her mind. She flung away from him and marched up to the horse-trader, who was in the middle of expounding the virtues of the young bay to Mauger. 'Master Pierre,' she interrupted, her voice and expression full of urgency, 'I want to ask you about the grey gelding and the chestnut mare over there.'

The man stared at her as if she had spoken in a different language. He was not accustomed to having his deals interrupted by women, and this one looked as if she was about to turn into a blazing termagant.

Mauger's lips tightened and he frowned at Julitta. 'Can you not see that we are busy,' he growled. 'Where is your modesty?'

'It flew out of the window the moment that I saw Cylu and Gisele's chestnut mare,' Julitta hotly retorted and pointed towards Pierre's other horses. 'Look for yourself.'

Mauger opened his mouth, shut it again with a snap, and glowered his way over to the line of animals. He walked around the grey gelding, while the bewildered groom looked on, and Pierre stood frowning, his hands on his hips and his moist lower lip thrust out.

'The same age,' Julitta declared. 'The same forehead mark and pink star on his muzzle. The groom told me that he and the mare were bought from a Basque trader.'

Mauger studied the chestnut mare too, and rubbed his aching forehead. 'Perhaps Benedict sold them,' he said to Julitta.

'Ben would never sell Cylu!' she declared with certainty. 'They have been together too long!'

'You cannot know Benedict's every thought,' he snapped irritably and turned to the trader who was watching them with wary eyes. 'We know these horses. They belong to my wife's sister and her husband.'

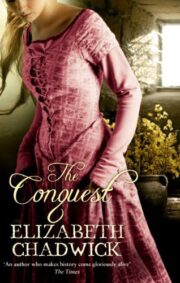

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.