They both looked at young Harry who was standing, watching the dancers, his face flushed with excitement, his eyes bright.

“Oh, Harry,” his mother said indulgently. “But there has never been a prince more handsome and more full of fun than Harry.”

The Spanish dance ended, and the king clapped his hands. “Now Harry and his sister,” he commanded. He did not want to force Arthur to dance in front of his new bride. The boy danced like a clerk, all gangling legs and concentration. But Harry was raring to go and was on the floor with his sister, Princess Margaret, in a moment. The musicians knew the young royals’ taste in music and struck up a lively galliard. Harry tossed his jacket to one side and threw himself into the dance, stripped down to his shirtsleeves like a peasant.

There was a gasp from the Spanish grandees at the young prince’s shocking behavior, but the English court smiled with his parents at his energy and enthusiasm. When the two had romped their way through the final turns and galop, everyone applauded, laughing. Everyone but Prince Arthur, who was staring into the middle distance, determined not to watch his brother dance. He came to with a start only when his mother put her hand on his arm.

“Please God he’s daydreaming of his wedding night,” his father remarked to Lady Margaret, his mother. “Though I doubt it.”

She gave a sharp laugh. “I can’t say I think much of the bride,” she said critically.

“You don’t?” he asked. “You saw the treaty yourself.”

“I like the price but the goods are not to my taste,” she said with her usual sharp wit. “She is a slight, pretty thing, isn’t she?”

“Would you rather a strapping milkmaid?”

“I’d like a girl with the hips to give us sons,” she said bluntly. “A nurseryful of sons.”

“She looks well enough to me,” he ruled. He knew that he would never be able to say how well she looked to him. Even to himself he should never even think it.

Catalina was put into her wedding bed by her ladies, María de Salinas kissed her good night, and Doña Elvira gave her a mother’s blessing; but Arthur had to undergo a further round of backslapping ribaldry before his friends and companions escorted him to her door. They put him into bed beside the princess who lay still and silent as the strange men laughed and bade them good night, and then the archbishop came to sprinkle the sheets with holy water and pray over the young couple. It could not have been a more public bedding unless they had opened the doors for the citizens of London to see the young people side by side, awkward as bolsters, in their marital bed. It seemed like hours to both of them until the doors were finally closed on the smiling, curious faces and the two of them were quite alone, seated upright against the pillows, frozen like a pair of shy dolls.

There was silence.

“Would you like a glass of ale?” Arthur suggested in a voice thin with nerves.

“I don’t like ale very much,” Catalina said.

“This is different. They call it wedding ale. It’s sweetened with mead and spices. It’s for courage.”

“Do we need courage?”

He was emboldened by her smile and got out of bed to fetch her a cup. “I should think we do,” he said. “You are a stranger in a new land, and I have never known any girls but my sisters. We both have much to learn.”

She took the cup of hot ale from him and sipped the heady drink. “Oh, that is nice.”

Arthur gulped down a cup and took another. Then he came back to the bed. Raising the cover and getting in beside her seemed an imposition; the idea of pulling up her night shift and mounting her was utterly beyond him.

“I shall blow out the candle,” he announced.

The sudden dark engulfed them, only the embers of the fire glowed red.

“Are you very tired?” he asked, longing for her to say that she was too tired to do her duty.

“Not at all,” she said politely, her disembodied voice coming out of the darkness. “Are you?”

“No.”

“Do you want to sleep now?” he asked.

“I know what we have to do,” she said abruptly. “All my sisters have been married. I know all about it.”

“I know as well,” he said, stung.

“I didn’t mean that you don’t know, I meant that you need not be afraid to start. I know what we have to do.”

“I am not afraid, it is just that I—”

To his absolute horror he felt her hand pull his nightshirt upwards, and touch the bare skin of his belly.

“I did not want to frighten you,” he said, his voice unsteady, desire rising up even though he was sick with fear that he would be incompetent.

“I am not afraid,” said Isabella’s daughter. “I have never been afraid of anything.”

In the silence and the darkness, he felt her take hold of him and grasp firmly. At her touch, he felt his desire well up so sharply that he was afraid he would come in her hand. With a low groan, he rolled over on top of her and found she had stripped herself naked to the waist, her nightgown pulled up. He fumbled clumsily and felt her flinch as he pushed against her. The whole process seemed quite impossible. There was no way of knowing what a man was supposed to do, nothing to help or guide him, no knowing the mysterious geography of her body, and then she gave a little cry of pain, stifled with her hand, and he knew he had done it. The relief was so great that he came at once, a half-painful, half-pleasurable rush which told him that, whatever his father thought of him, whatever his brother Harry thought of him, the job was done and he was a man and a husband; and the princess was his wife and no longer a virgin untouched.

Catalina waited till he was asleep, and then she got up and washed herself in her privy chamber. She was bleeding, but she knew it would stop soon. The pain was no worse than she had expected. Isabel her sister had said it was not as bad as falling from a horse, and she had been right. Margot, her sister-in-law, had said that it was paradise; but Catalina could not imagine how such deep embarrassment and discomfort could add up to bliss—and concluded that Margot was exaggerating, as she often did.

Catalina came back to the bedroom. But she did not go back to the bed. Instead she sat on the floor by the fire, hugging her knees and watching the embers.

“Not a bad day,” I say to myself, and I smile; it is my mother’s phrase. I want to hear her voice so much that I am saying her words to myself. Often, when I was little more than a baby and she had spent a long day in the saddle, inspecting the forward scouting parties, riding back to chivvy up the slower train, she would come into her tent, kick off her riding boots, drop down to the rich Moorish rugs and cushions by the fire in the brass brazier, and say, “Not a bad day.”

“Is there ever a bad day?” I once asked her.

“Not when you are doing God’s work,” she replied seriously. “There are days when it is easy and days when it is hard. But if you are on God’s work, then there are never bad days.”

I don’t for a moment doubt that bedding Arthur, even my brazen touching him and drawing him into me, is God’s work. It is God’s work that there should be an unbreakable alliance between Spain and England. Only with England as a reliable ally can Spain challenge the spread of France. Only with English wealth, and especially English ships, can we Spanish take the war against wickedness to the very heart of the Moorish empires in Africa and Turkey. The Italian princes are a muddle of rival ambitions, the French are a danger to every neighbor. It has to be England who joins the crusade with Spain to maintain the defense of Christendom against the terrifying might of the Moors—whether they be black Moors from Africa, the bogeymen of my childhood, or light-skinned Moors from the dreadful Ottoman Empire. And once they are defeated, then the crusaders must go on, to India, to the East, as far as they have to go to challenge and defeat the wickedness that is the religion of the Moors. My great fear is that the Saracen kingdoms stretch forever, to the end of the world, and even Cristóbal Colón does not know where that is.

“What if there is no end to them?” I once asked my mother as we leaned over the sun-warmed walls of the fort and watched the dispatch of a new group of Moors leaving the city of Granada, their baggage loaded on mules, the women weeping, the men with their heads bowed low, the flag of St. James now flying over the red fort where the crescent had rippled for seven centuries, the bells ringing for Mass where once horns had blown for heretic prayers. “What if now we have defeated these, they just go back to Africa and in another year, they come again?”

“That is why you have to be brave, my Princess of Wales,” my mother had answered. “That is why you have to be ready to fight them whenever they come, wherever they come. This is war till the end of the world, till the end of time when God finally ends it. It will take many shapes. It will never cease. They will come again and again, and you will have to be ready in Wales as we will be ready in Spain. I bore you to be a fighting princess as I am a Queen Militant. Your father and I placed you in England as María is placed in Portugal, as Juana is placed with the Hapsburgs in the Netherlands. You are there to defend the lands of your husbands and to hold them in alliance with us. It is your task to make England ready and keep it safe. Make sure that you never fail your country, as your sisters must never fail theirs, as I have never failed mine.”

Catalina was awakened in the early hours of the morning by Arthur gently pushing between her legs. Resentfully, she let him do as he wanted, knowing that this was the way to get a son and make the alliance secure. Some princesses, like her mother, had to fight their way in open warfare to secure their kingdom. Most princesses, like her, had to endure painful ordeals in private. It did not take long, and then he fell asleep. Catalina lay as still as a frozen stone in order not to wake him again.

He did not stir until daybreak, when his grooms of the bedchamber rapped brightly on the door. He rose up with a slightly embarrassed “Good morning” to her and went out. They greeted him with cheers and marched him in triumph to his own rooms. Catalina heard him say, vulgarly, boastfully, “Gentlemen, this night I have been in Spain,” and heard the yell of laughter that applauded his joke. Her ladies came in with her gown and heard the men’s laughter. Doña Elvira raised her thin eyebrows to heaven at the manners of these English.

“I don’t know what your mother would say,” Doña Elvira remarked.

“She would say that words count less than God’s will, and God’s will has been done,” Catalina said firmly.

It was not like this for my mother. She fell in love with my father on sight and she married him with great joy. When I grew older I began to understand that they felt a real desire for each other—it was not just a powerful partnership of a great king and queen. My father might take other women as his lovers; but he needed his wife, he could not be happy without her. And my mother could not even see another man. She was blind to anybody but my father. Alone, of all the courts in Europe, the court of Spain had no tradition of love play, of flirtation, of adoration of the queen in the practice of courtly love. It would have been a waste of time. My mother simply did not notice other men and when they sighed for her and said her eyes were as blue as the skies she simply laughed and said, “What nonsense,” and that was an end to it.

When my parents had to be apart they wrote every day, he would not move one step without telling her of it, and asking for her advice. When he was in danger she hardly slept.

He could not have got through the Sierra Nevada if she had not been sending him men and digging teams to level the road for him. No one else could have driven a road through there. He would have trusted no one else to support him, to hold the kingdom together as he pushed forwards. She could have conquered the mountains for no one else; he was the only one that could have attracted her support. What looked like a remarkable unity of two calculating players was deceptive—it was their passion which they played out on the political stage. She was a great queen because that was how she could evoke his desire. He was a great general in order to match her. It was their love, their lust, which drove them; almost as much as God.

We are a passionate family. When Isabel, my sister, now with God, came back from Portugal a widow she swore that she had loved her husband so much that she would never take another. She had been with him for only six months but she said that without him, life had no meaning. Juana, my second sister, is so in love with her husband, Philip, that she cannot bear to let him out of her sight. When she learns that he is interested in another woman, she swears that she will poison her rival—she is quite mad with love for him. And my brother…my darling brother, Juan…simply died of love. He and his beautiful wife, Margot, were so passionate, so besotted with each other that his health failed; he was dead within six months of their wedding. Is there anything more tragic than a young man dying six months into his marriage? I come from passionate stock—but what about me? Shall I ever fall in love?

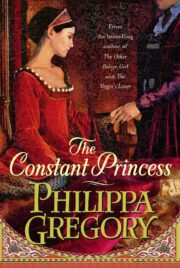

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.