I love him. I did not think it possible, but I love him. I have fallen in love with him. I look at myself in the mirror, in wonderment, as if I am changed, as everything else is changed. I am a young woman in love with my husband. I am in love with the Prince of Wales. I, Catalina of Spain, am in love. I wanted this love, I thought it was impossible, and I have it. I am in love with my husband, and we shall be King and Queen of England. Who can doubt now that I am chosen by God for His especial favor? He brought me from the dangers of war to safety and peace in the Alhambra Palace, and now He has given me England and the love of the young man who will be its king.

In a sudden rush of emotion I put my hands together and pray: “Oh, God, let me love him forever, do not take us from each other as Juan was taken from Margot, in their first months of joy. Let us grow old together, let us love each other forever.”

Ludlow Castle, January 1502

THE WINTER SUN WAS LOW AND RED over the rounded hills as they rattled through the great gate that pierced the stone wall around Ludlow. Arthur, who had been riding beside the litter, shouted to Catalina over the noise of the hooves on the cobbles. “This is Ludlow, at last!”

Ahead of them the men-at-arms shouted: “Make way for Arthur! Prince of Wales!” and the doors banged open and people tumbled out of their houses to see the procession go by.

Catalina saw a town as pretty as a tapestry. The timbered second stories of the crowded buildings overhung cobbled streets with prosperous little shops and working yards tucked cozily underneath them on the ground floor. The shopkeepers’ wives jumped up from their stools set outside the shops to wave to her, and Catalina smiled and waved back. From the upper stories the glovers’ girls and shoemakers’ apprentices, the goldsmiths’ boys and the spinsters leaned out and called her name. Catalina laughed and caught her breath as one young lad looked ready to overbalance but was hauled back in by his cheering mates.

They passed a great bull ring with a dark-timbered inn, as the church bells of the half dozen religious houses, college, chapels and hospital of Ludlow started to peal their bells to welcome the prince and his bride home.

Catalina leaned forwards to see her castle and noted the unassailable march of the outer bailey. The gate was flung open, they went in, and found the greatest men of the town—the mayor, the church elders, the leaders of the wealthy trades guilds—assembled to greet them.

Arthur pulled up his horse and listened politely to a long speech in Welsh and then in English.

“When do we eat?” Catalina whispered to him in Latin and saw his mouth quiver as he held back a smile.

“When do we go to bed?” she breathed, and had the satisfaction of seeing his hand tremble with desire on the rein. She gave a little giggle and ducked back into the litter until finally the interminable speeches of welcome were finished and the royal party could ride on through the great gate of the castle to the inner bailey.

It was a neat castle, as sound as any border castle in Spain. The curtain wall marched around the inner bailey high and strong, made in a curious rosy-colored stone that made the powerful walls more warm and domestic.

Catalina’s eye, sharpened by her training, looked from the thick walls to the well in the outer bailey, the well in the inner bailey, took in how one defensible area led to another, thought that a siege could be held off for years. But it was small, it was like a toy castle, something her father would build to protect a river crossing or a vulnerable road. Something a very minor lord of Spain would be proud to have as his home.

“Is this it?” she asked blankly, thinking of the city that was housed inside the walls of her home, of the gardens and the terraces, of the hill and the views, of the teeming life of the town center, all inside defended walls. Of the long hike for the guards: if they went all around the battlements they would be gone for more than an hour. At Ludlow a sentry would complete the circle in minutes. “Is this it?”

At once he was aghast. “Did you expect more? What were you expecting?”

She would have caressed his anxious face if there had not been hundreds of people watching. She made herself keep her hands still. “Oh, I was foolish. I was thinking of Richmond.” Nothing in the world would have made her say that she was thinking of the Alhambra.

He smiled, reassured. “Oh, my love. Richmond is new-built, my father’s great pride and joy. London is one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and the palace matches its size. But Ludlow is only a town, a great town in the Marches for sure, but a town. But it is wealthy, you will see, and the hunting is good and the people are welcoming. You will be happy here.”

“I am sure of it,” said, Catalina smiling at him, putting aside the thought of a palace built for beauty, only for beauty, where the builders had thought firstly where the light would fall and what reflections it would make in still pools of marble.

She looked around her and saw, in the center of the inner bailey, a curious circular building like a squat tower.

“What’s that?” she asked, struggling out of the litter as Arthur held her hand.

He glanced over his shoulder. “It’s our round chapel,” he said negligently.

“A round chapel?”

“Yes, like in Jerusalem.”

At once she recognized with delight the traditional shape of the mosque—designed and built in the round so that no worshipper was better placed than any others, because Allah is praised by the poor man as well as the rich. “It’s lovely.”

Arthur glanced at her in surprise. To him it was only a round tower built with the pretty plum-colored local stone, but he saw that it glowed in the afternoon light and radiated a sense of peace.

“Yes,” he said, hardly noticing it. “Now this”—he indicated the great building facing them, with a handsome flight of steps up to the open door—“this is the great hall. To the left are the council chambers of Wales and, above them, my rooms. To the right are the guest bedrooms and chambers for the warden of the castle and his lady: Sir Richard and Lady Margaret Pole. Your rooms are above, on the top floor.”

He saw her swift reaction. “She is here now?”

“She is away from the castle at the moment.”

She nodded. “There are buildings behind the great hall?”

“No. It is set into the outer wall. This is all of it.”

Catalina schooled herself to keep her face smiling and pleasant.

“We have more guest rooms in the outer bailey,” he said defensively. “And we have a lodge house, as well. It is a busy place, merry. You will like it.”

“I am sure I will.” She smiled. “And which are my rooms?”

He pointed to the highest windows. “See up there? On the right-hand side, matching mine, but on the opposite side of the hall.”

She looked a little daunted. “But how will you get to my rooms?” she asked quietly.

He took her hand and led her, smiling to his right and to his left, towards the grand stone stairs to the double doors of the great hall. There was a ripple of applause, and their companions fell in behind them. “As My Lady the King’s Mother commanded me, four times a month I shall come to your room in a formal procession through the great hall, ”he said. He led her up the steps.

“Oh.” She was dashed.

He smiled down at her. “And all the other nights, I shall come to you along the battlements,” he whispered. “There is a private door that goes from your rooms to the battlements that run all around the castle. My rooms go onto them too. You can walk from your rooms to mine whenever you wish and nobody will know whether we are together or not. They will not even know whose room we are in.”

He loved how her face lit up. “We can be together whenever we want?”

“We will be happy here.”

Yes I will, I will be happy here. I will not mourn like a Persian for the beautiful courts of his home and declare that there is nowhere else fit for life. I will not say that these mountains are a desert without oases, like a Berber longing for his birthright. I will accustom myself to Ludlow, and I will learn to live here, on the border, and later in England. My mother is not just a queen, she is a soldier, and she raised me to know my duty and to do it. It is my duty to learn to be happy here and to live here without complaining.

I may never wear armor as she did, I may never fight for my country, as she did; but there are many ways to serve a kingdom, and to be a merry, honest, constant queen is one of them. If God does not call me to arms, He may call me to serve as a lawgiver, as a bringer of justice. Whether I defend my people by fighting for them against an enemy or by fighting for their freedom in the law, I shall be their queen, heart and soul, Queen of England.

It was nighttime, past midnight. Catalina glowed in the firelight. They were in bed, sleepy, but too desirous of each other for sleep.

“Tell me a story.”

“I have told you dozens of stories.”

“Tell me another. Tell me the one about Boabdil giving up the Alhambra Palace with the golden keys on a silk cushion and going away crying.”

“You know that one. I told it to you last night.”

“Then tell me the story about Yarfa and his horse that gnashed its teeth at Christians.”

“You are a child. And his name was Yarfe.”

“But you saw him killed?”

“I was there, but I didn’t see him actually die.”

“How could you not watch it?”

“Well, partly because I was praying as my mother ordered me to, and because I was a girl and not a bloodthirsty, monstrous boy.”

Arthur tossed an embroidered cushion at her head. She caught it and threw it back at him.

“Well, tell me about your mother pawning her jewels to pay for the crusade.”

She laughed again and shook her head, making her auburn hair swing this way and that. “I shall tell you about my home,” she offered.

“All right.” He gathered the purple blanket around them both and waited.

“When you come through the first door to the Alhambra, it looks like a little room. Your father would not stoop to enter a palace like that.”

“It’s not grand?”

“It’s the size of a little merchant’s hall in the town here. It is a good hall for a small house in Ludlow, nothing more.”

“And then?”

“And then you go into the courtyard and from there into the golden chamber.”

“A little better?”

“It is filled with color, but still it is not much bigger. The walls are bright with colored tiles and gold leaf and there is a high balcony, but it is still only a little space.”

“And then where shall we go today?”

“Today we shall turn right and go into the Court of the Myrtles.”

He closed his eyes, trying to remember her descriptions. “A courtyard in the shape of a rectangle, surrounded by high buildings of gold.”

“With a huge, dark wooden doorway framed with beautiful tiles at the far end.”

“And a lake, a lake of a simple rectangle shape, and on either side of the water, a hedge of sweet-scented myrtle trees.”

“Not a hedge like you have,” she demurred, thinking of the ragged edges of the Welsh fields in their struggle of thorn and weed.

“Like what, then?” he asked, opening his eyes.

“A hedge like a wall,” she said. “Cut straight and square, like a block of green marble, like a living green sweet-scented statue. And the gateway at the end is reflected back in the water, and the arch around it, and the building that it is set in. So that the whole thing is mirrored in ripples at your feet. And the walls are pierced with light screens of stucco, as airy as paper, like white-on-white embroidery. And the birds—”

“The birds?” he asked, surprised, for she had not told him of them before.

She paused while she thought of the word. “Apodes?” she said in Latin.

“Apodes? Swifts?”

She nodded. “They flow like a turbulent river of birds just above your head, round and round the narrow courtyard, screaming as they go, as fast as a cavalry charge. They go like the wind, round and round, as long as the sun shines on the water they go round, all day. And at night—”

“At night?”

She made a little gesture with her hands, like an enchantress. “At night they disappear, you never see them settle or nest. They just disappear—they set with the sun, but at dawn they are there again, like a river, like a flood.” She paused. “It is hard to describe,” she said in a small voice. “But I see it all the time.”

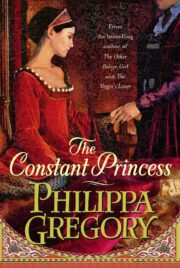

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.