The king promised me rooms at court and I thought that he had at last forgiven me. I thought he was offering me to come to court, to live in the rooms of a princess and to see Harry. But when I moved my household there I found that I was given the worst rooms, allocated the poorest service, unable to see the prince except on the most formal of state occasions. One dreadful day, the court left on progress without telling us and we had to dash after them, finding our way down the unmarked country lanes, as unwanted and as irrelevant as a wagon filled with old goods. When we caught up, no one had noticed that we were missing and I had to take the only rooms left: over the stables, like a servant.

The king stopped paying my allowance; his mother did not press my case. I had no money of my own at all. I lived despised on the fringe of the court, with Spaniards who served me only because they could not leave. They were trapped like me, watching the years slide by, getting older and more resentful till I felt like the sleeping princess of the fairy tale and thought that I would never wake.

I lost my vanity—my proud sense that I could be cleverer than that old fox who was my father-in-law and that sharp vixen his mother. I learned that he had betrothed me to his son Prince Harry not because he loved and forgave me, but because it was the cleverest and cruelest way to punish me. If he could not have me, then he could make sure that no one had me. It was a bitter day when I realized that.

And then Philip died and my sister Juana was a widow like me, and King Henry came up with a plan to marry her, my poor sister—driven from her wits by the loss of her husband—and put her over me, on the throne of England, where everyone would see that she was crazed, where everyone could see the bad blood which I share, where everyone would know that he had made her queen and thrown me down to nothing. It was a wicked plan, certain to shame and distress both me and Juana. He would have done it if he could, and he made me his pander as well—he forced me to recommend him to my father. Under my father’s orders I spoke to the king of Juana’s beauty; under the king’s orders I urged my father to accept his suit, all the time knowing that I was betraying my very soul. I lost my ability to refuse King Henry my persecutor, my father-in-law, my would-be seducer. I was afraid to say no to him. I was very much reduced that day.

I lost my vanity in my allure, I lost my confidence in my intelligence and skills, but I never lost my will to live. I was not like my mother, I was not like Juana, I did not turn my face to the wall and long for my pain to be over. I did not slide into the wailing grief of madness nor into the gentle darkness of sloth. I gritted my teeth, I am the constant princess, I don’t stop when everyone else stops. I carried on. I waited. Even when I could do nothing else, I could still wait. So I waited.

These were not the years of my defeat; these were the years when I grew up, and it was a bitter maturing. I grew from a girl of sixteen ready for love to a half-orphaned, lonely widow of twenty-three. These were the years when I drew on the happiness of my childhood in the Alhambra and my love for my husband to sustain me, and swore that whatever the obstacles before me, I should be Queen of England. These were the years when, though my mother was dead, she lived again through me. I found her determination inside me, I found her courage inside me, I found Arthur’s love and optimism inside me. These were the years when although I had nothing left—no husband, no mother, no friends, no fortune and no prospects—I swore that however disregarded, however poor, however unlikely a prospect, I would still be Queen of England.

News, always slow to reach the bedraggled Spaniards on the fringe of the royal court, filtered through that Harry’s sister the Princess Mary was to be married, gloriously, to Prince Charles, son of King Philip and Queen Juana, grandson to both the Emperor Maximilian and King Ferdinand. Amazingly, at this of all moments, King Ferdinand at last found the money for Catalina’s dowry and packed it off to London.

“My God, we are freed. There can be a double wedding. I can marry him,” Catalina said, heartfelt, to the Spanish emissary, Don Gutierre Gómez de Fuensalida.

He was pale with worry, his yellow teeth nipping at his lips. “Oh, Infanta, I hardly know how to tell you. Even with this alliance, even with the dowry money—dear God, I fear it comes too late. I fear it will not help us at all.”

“How can it be? Princess Mary’s betrothal only deepens the alliance with my family.”

“What if…” he started and broke off. He could hardly speak of the danger that he foresaw. “Princess, all the English know that the dowry money is coming, but they do not speak of your marriage. Oh, Princess, what if they plan an alliance that does not include Spain? What if they plan an alliance between the emperor and King Henry? What if the alliance is for them to go to war against Spain?”

She turned her head. “It cannot be.”

“What if it is?”

“Against the boy’s own grandfather?” she demanded.

“It would only be one grandfather, the emperor, against another, your father.”

“They would not,” she said determinedly.

“They could.”

“King Henry would not be so dishonest.”

“Princess, you know that he would.”

She hesitated. “What is it?” she suddenly demanded, sharp with irritation. “There is something else. Something you are not telling me. What is it?”

He paused, a lie in his mouth; then he told her the truth. “I am afraid, I am very afraid, that they will betroth Prince Harry to Princess Eleanor, the sister of Charles.”

“They cannot, he is betrothed to me.”

“They may plan it as part of a great treaty. Your sister Juana to marry the king, your nephew Charles for Princess Mary, and your niece Eleanor for Prince Harry.”

“But what about me? Now that my dowry money is on its way at last?”

He was silent. It was painfully apparent that Catalina was excluded by these alliances and no provision made for her.

“A true prince has to honor his promise,” she said passionately. “We were betrothed by a bishop before witnesses. It is a solemn oath.”

The ambassador shrugged, hesitated. He could hardly make himself tell her the worst news of all. “Your Grace, Princess, be brave. I am afraid he may withdraw his oath.”

“He cannot.”

Fuensalida went further. “Indeed, I am afraid it is already withdrawn. He may have withdrawn it years ago.”

“What?” she asked sharply. “How?”

“A rumor, I cannot be sure of it. But I am afraid…” He broke off.

“Afraid of what?”

“I am afraid that the prince may be already released from his betrothal to you.” He hesitated at the sudden darkening of her face. “It will not have been his choice,” he said quickly. “His father is determined against us.”

“How could he? How can such a thing be done?”

“He could have sworn an oath that he was too young, that he was under duress. He may have declared that he did not want to marry you. Indeed, I think that is what he has done.”

“He was not under duress!” Catalina exclaimed. “He was utterly delighted. He has been in love with me for years, I am sure he still is. He did want to marry me!”

“An oath sworn before a bishop that he was not acting of his own free will would be enough to secure his release from his promise.”

“So all these years that I have been betrothed to him, and acted on that premise, all these years that I have waited and waited and endured…” She could not finish. “Are you telling me that for all these years, when I believed that we had them tied down, contracted, bound, he has been free?”

The ambassador nodded; her face was so stark and shocked that he could hardly find his voice.

“This is…a betrayal,” she said. “A most terrible betrayal.” She choked on the words. “This is the worst betrayal of all.”

He nodded again.

There was a long, painful silence. “I am lost,” she said simply. “Now I know it. I have been lost for years and I did not know. I have been fighting a battle with no army, with no support. Actually—with no cause. You tell me that I have been defending a cause that was gone long ago. I was fighting for my betrothal but I was not betrothed. I have been all alone, all this long time. And now I know it.”

Still she did not weep, though her blue eyes were horrified.

“I made a promise,” she said, her voice harsh. “I made a solemn and binding promise.”

“Your betrothal?”

She made a little gesture with her hand. “Not that. I swore a promise. A deathbed promise. Now you tell me it has all been for nothing.”

“Princess, you have stayed at your post, as your mother would have wanted you to do.”

“I have been made a fool!” burst out of her, from the depth of her shock. “I have been fighting for the fulfillment of a vow, not knowing that the vow was long broken.”

He could say nothing; her pain was too raw for any soothing words.

After a few moments, she raised her head. “Does everyone know but me?” she asked bleakly.

He shook his head. “I am sure it was kept most secret.”

“My Lady the King’s Mother,” she predicted bitterly. “She will have known. It will have been her decision. And the king, the prince himself, and if he knew, then the Princess Mary will know—he would have told her. And his closest companions…” She raised her head. “The king’s mother’s ladies, the princess’s ladies. The bishop that he swore to, a witness or two. Half the court, I suppose.” She paused. “I thought that at least some of them were my friends,” she said.

The ambassador shrugged. “In a court there are no friends, only courtiers.”

“My father will defend me from this…cruelty!” she burst out. “They should have thought of that before they treated me so! There will be no treaties for England with Spain when he hears about this. He will take revenge for this abuse of me.”

He could say nothing, and in the still, silent face that he turned to her she saw the worst truth.

“No,” she said simply. “Not him. Not him as well. Not my father. He did not know. He loves me. He would never injure me. He would never abandon me here.”

Still he could not tell her. He saw her take a deep breath.

“Oh. Oh. I see. I see from your silence. Of course. He knows, of course he knows, doesn’t he? My father? The dowry money is just another trick. He knows of the proposal to marry Prince Harry to Princess Eleanor. He has been leading the king on to think that he can marry Juana. He ordered me to encourage the king to marry Juana. He will have agreed to this new proposal for Prince Harry. And so he knows that the prince has broken his oath to me? And is free to marry?”

“Princess, he has told me nothing. But I think he must know. But perhaps he plans…”

Her gesture stopped him. “He has given up on me. I see. I have failed him and he has cast me aside. I am indeed alone.”

“So shall I try to get us home now?” Fuensalida asked quietly. Truly, he thought, it had become the very pinnacle of his ambitions. If he could get this doomed princess home to her unhappy father and her increasingly deranged sister, the new Queen of Castile, he would have done the best he could in a desperate situation. Nobody would marry Catalina of Spain now she was the daughter of a divided kingdom. Everyone could see that the madness in her blood was coming out in her sister. Not even Henry of England could pretend that Juana was fit to marry when she was on a crazed progress across Spain with her dead husband’s coffin. Ferdinand’s tricky diplomacy had rebounded on him and now everyone in Europe was his enemy, with two of the most powerful men in Europe allied to make war against him. Ferdinand was lost and going down. The best that this unlucky princess could expect was a scratch marriage to some Spanish grandee and retirement to the countryside, with a chance to escape the war that must come. The worst was to remain trapped and in poverty in England, a forgotten hostage that no one would ransom. A prisoner who would be soon forgotten, even by her jailers.

“What shall I do?” Finally she accepted danger. He saw her take it in. Finally, she understood that she had lost. He saw her, a queen in every inch, learn the depth of her defeat. “I must know what I should do. Or I shall be hostage, in an enemy country, with no one to speak for me.”

He did not say that he had thought her just that, ever since he had arrived.

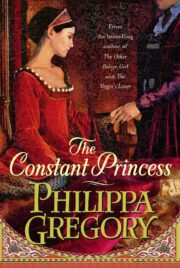

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.