Mr Drelincourt, considerably astonished, sat forward to see more closely, and called to his postilions: “What is it? Why don’t they go on? Is it an accident?”

Then he saw Lord Lethbridge spring down from the other chaise, and he shrank back in his seat, his heart jumping with fright.

Lethbridge walked up to Mr Drelincourt’s equipage, and that shivering gentleman pulled himself together with an effort. It would not do for him to cower in the corner, so he leaned forward and let down the window. “Is it you, indeed, my lord?” he said in a high voice. “I could scarce believe my eyes! What can have brought you out of town?”

“Why, you, Crosby, you!” said his lordship mockingly. “Pray step down out of that chaise. I should like to have a little talk with you.”

Mr Drelincourt clung to the window frame and gave an unnatural laugh. “Oh, your pleasantries, my lord! I am on my way to Meering, you know, to my cousin’s. I—I think it is already on five o’clock, and he dines at five.”

“Crosby, come down!” said Lethbridge, with such an alarm-;ng glitter in his eyes that Mr Drelincourt was quite cowed, and began to fumble with the catch of the door. He climbed down carefully, under the grinning stare of his postilions. “I vow I can’t imagine what you was wanting to say to me,” he said. “And I am late, you know. I ought to be on my way.”

His arm was taken in an ungentle grip. “Walk with me a little way, Crosby,” said his lordship. “Do you not find these country roads quite charming? I am sure you do. And so you are bound for Meering? Was not that a rather sudden decision, Crosby?”

“Sudden?” stammered Mr Drelincourt, wincing at the pressure of his lordship’s fingers above his elbow. “Oh, not at all, my lord, not in the least! I told Rule I might come down. I have had it in mind some days, I assure you.”

“It has nothing to do, of course, with a certain brooch?” purred Lethbridge.

“A b-brooch? I don’t understand you, my lord!”

“A ring-brooch of pearls and diamonds, picked up in my house last night,” said his lordship.

Mr Drelincourt’s knees shook. “I protest, sir, I—I am at a loss! I—”

“Crosby, give me that brooch,” said Lethbridge menacingly.

Mr Drelincourt made an attempt to pull his arm away. “My lord, I don’t understand your tone! I tell you frankly, I don’t like it. I don’t take your meaning.”

“Crosby,” said his lordship, “you will give me that brooch, or I will take you by the scruff of your neck and shake you like the rat you are!”

“Sir!” said Mr Drelincourt, his teeth chattering together, “this is monstrous! Monstrous!”

“It is indeed monstrous,” agreed his lordship. “You are a thief, Mr Crosby Drelincourt.”

Mr Drelincourt flushed scarlet. “It was not your brooch, sir!”

“Or yours!” swiftly replied Lethbridge. “Hand it over!”

“I—I have called a man out for less!” blustered Crosby.

“That’s your humour, is it?” said Lethbridge. “It’s not my practice to fight with thieves; I use a cane instead. But I might make an exception in your case.”

To Mr Drelincourt’s horror, he thrust forward his sword hilt and patted it. That unfortunate gentleman licked his lips and said quaveringly: “I shall not fight you, sir. The brooch is more mine than yours!”

“Hand it over!” said Lethbridge.

Mr Drelincourt hesitated, read a look in his lordship’s face there was no mistaking, and slowly inserted his finger and thumb into his waistcoat pocket. The next moment the brooch lay in Lethbridge’s hand.

“Thank you, Crosby,” he said, in a way that made Mr Drelincourt long for the courage to hit him. “I thought I should be able to persuade you. You may now resume your journey to Meering—if you think it still worth while. If you don’t—you may join me at the Sun in Maidenhead, where I propose to dine and sleep. I almost feel I owe you a dinner for spoiling your game so unkindly.” He turned, leaving Mr Drelincourt speechless with indignation, and walked back to his chaise, which had by this time drawn up to the side of the road, facing towards London again. He climbed lightly into it and drove off, airily waving his hand to Mr Drelincourt, still standing in the dusty road.

Mr Drelincourt gazed after him, rage seething up in him. Spoiled his game, had he? There might be two words to that! He hurried back to his own chaise, saw the looks of rich enjoyment on the postilions’ faces, and swore at them to drive on.

It was only six miles to Meering from the Thicket, but by the time the chaise turned in at the Lodge gates it was close on six o’clock. The house was situated a mile from the gates, in the middle of a very pretty park, but Mr Drelincourt was in no mood to admire the fine oaks, and rolling stretches of turf, and sat in a fret of impatience while his tired horses drew him up the long avenue to the house.

He found his cousin and Mr Gisborne lingering over their port in the dining-room, which apartment was lit by candles. It might be broad daylight outside, but my lord had a constitutional dislike of dining by day, and excluded it by having the heavy curtains drawn across the windows.

Both he and Mr Gisborne were in riding-dress. My lord was lounging in a high-backed chair at the head of the table, one leg, encased in a dusty top-boot, thrown negligently over the arm. He looked up as the footman opened the door to admit Mr Drelincourt, and for a moment sat perfectly still, the look of good humour fading from his face. Then he picked up his quizzing-glass with some deliberation, and surveyed his cousin through it. “Dear me!” he said. “Now why?”

This was not a very promising start, but his anger had chased from Mr Drelincourt’s mind all memory of his last meeting with the Earl, and he was undaunted. “Cousin,” he said, his words tripping over one another. “I am here on a matter of grave moment. I must beg a word with you alone!”

“I imagine it must indeed be of grave moment to induce you to come over thirty miles in pursuit of me,” said his lordship.

Mr Gisborne got up. “I will leave you, sir.” He bowed slightly to Mr Drelincourt, who paid not the slightest heed to him, and went out.

Mr Drelincourt pulled a chair out from the table and sat down. “I regret extremely, Rule, but you must prepare yourself for the most unpleasant tidings. If I did not consider it my duty to appraise you of what I have discovered, I should shrink from the task!”

The Earl did not seem to be alarmed. He still sat at his ease, one hand lying on the table, the fingers crooked round the stem of his wine-glass, his calm gaze resting on Mr Drelincourt’s face. “This self-immolation on the altar of duty is something new to me,” he remarked. “I daresay my nerves will prove strong enough to enable me to hear your tidings with—I trust—tolerable equanimity.”

“I trust so, Rule, I do indeed trust so!” said Mr Drelincourt, his eyes snapping. “You are pleased to sneer at my notion of duty—”

“I hesitate to interrupt you, Crosby, but you may have noticed that I never sneer.”

“Very well, cousin, very well! Be that as it may, you will allow that I have my share of family pride.”

“Certainly, if you tell me so,” replied the Earl gently.

Mr Drelincourt flushed. “I do tell you so! Our name—our honour, mean as much to me as to you, I believe! It is on that score that I am here now.”

“If you have come all this way to inform me that the catchpolls are after you, Crosby, it is only fair to tell you that you are wasting your time.”

“Very humorous, my lord!” cried Mr Drelincourt. “My errand, however, concerns you more nearly than that! Last night—I should rather say this morning, for it was long past two by my watch—I had occasion to visit my Lord Lethbridge.”

“That is, of course, interesting,” said the Earl. “It seems an odd hour for visiting, but I have sometimes thought, Crosby, that you are an odd creature.”

Mr Drelincourt’s bosom swelled. “There is nothing very odd, I think, in sheltering from the rain!” he said. “I was upon my way to my lodging from South Audley Street, and chanced to turn down Half-Moon Street. I was caught in a shower of rain, but observing the door of my Lord Lethbridge’s house to stand—inadvertently, I am persuaded—ajar, I stepped in. I found his lordship in a dishevelled condition in the front saloon, where a vastly elegant supper was spread, covers, my lord, being laid for two.”

“You shock me infinitely,” said the Earl, and leaning a little forward, picked up the decanter and refilled his glass.

Mr Drelincourt uttered a shrill laugh. “You may well say so! His lordship seemed put out at seeing me, remarkably put out!”

“That,” said the Earl, “I can easily understand. But pray continue, Crosby.”

“Cousin,” said Mr Drelincourt earnestly, “I desire you to believe that it is with the most profound reluctance that I do so. While I was with Lord Lethbridge, my attention was attracted to something that lay upon the floor, partly concealed by a rug. Something, Rule, that sparkled. Something—”

“Crosby,” said his lordship wearily, “your eloquence is no doubt very fine, but I must ask you to bear in mind that I have been in the saddle most of the day, and spare me any more of it. I am not really very curious to know, but you seem to be anxious to tell me: what was it that attracted your attention?”

Mr Drelincourt swallowed his annoyance. “A brooch, my lord! A lady’s corsage brooch!”

“No wonder that Lord Lethbridge was not pleased to see you,” remarked Rule.

“No wonder, indeed!” said Mr Drelincourt. “Somewhere in the house a lady was concealed at that very moment. Unseen, cousin, I picked up the brooch and slipped it into my pocket.”

The Earl raised his brows. “I think I said that you were an odd creature, Crosby.”

“It may appear so, but I had a good reason for my action. Had it not been for the fact that Lord Lethbridge pursued me on my journey here, and by force wrested the brooch from me, I should lay it before you now. For that brooch is very well known both to you and me. A ring-brooch, cousin, composed of pearls and diamonds in two circles!”

The Earl never took his eyes from Mr Drelincourt’s; it may have been a trick of the shadows thrown by the candles on the tables, but his face looked unusually grim. He swung his leg down from the arm of the chair leisurely, but still leaned back at his ease. “Yes, Crosby, a ring-brooch of pearls and diamonds?”

“Precisely, cousin! A brooch I recognized at once. A brooch that belongs to the fifteenth-century set which you gave to your—”

He got no further. In one swift movement the Earl was up, and had seized Mr Drelincourt by the throat, dragging him out of his chair, and half across the corner of the table that separated them. Mr Drelincourt’s terrified eyes goggled up into blazing grey ones. He clawed ineffectively at my lord’s hands. Speech was choked out of him. He was shaken to and fro till the teeth rattled in his head. There was a roaring in his ears, but he heard my lord’s voice quite distinctly. “You lying, mischief-making little cur!” it said. “I have been too easy with you. You dare to bring me your foul lies about my wife, and you think that I may believe them! By God, I am of a mind to kill you now!”

A moment more the crushing grip held, then my lord flung his cousin away from him, and brushed his hands together in a gesture infinitely contemptuous.

Mr Drelincourt reeled back, grasping and clutching at the air, and fell with a crash on to the floor, and stayed there, cowering away like a whipped mongrel.

The Earl looked down at him for a moment, a smile quite unlike any Mr Drelincourt had ever seen curling his fine mouth. Then he leaned back against the table, half sitting on it, supported by his hands, and said: “Get up, my friend. You are not yet dead.”

Mr Drelincourt picked himself up and tried mechanically to straighten his wig. His throat felt mangled, and his legs were shaking so that he could hardly stand. He staggered to a chair and sank into it.

“You said, I think, that Lord Lethbridge took this famous brooch from you? Where?”

Mr Drelincourt managed to say, though hoarsely: “Maidenhead.”

“I trust he will return it to its rightful owner. You realize, do you, Crosby, that your genius for recognizing my property is sometimes at fault?”

Mr Drelincourt muttered: “I thought it was—I—I may have been mistaken.”

“You were mistaken,” said his lordship.

“Yes, I—yes, I was mistaken. I beg pardon, I am sure. I am very sorry, cousin.”

“You will be still more sorry, Crosby, if one word of this passes your lips again. Do I make myself plain?”

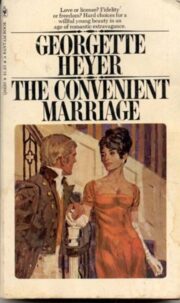

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.