“Very,” said Sir Richard. “But perhaps a trifle—shall we say, crude?”

“Oh!” Pen digested this. “You mean that she did not like my not pretending that Fred was in love with me?”

“I think it just possible,” said Sir Richard gravely.

“Well, I am sorry if I wounded her feelings, but truly I don’t think she has the least sensibility. I only said what I thought. But it put her in such a rage that there was nothing for it but to escape. So I did.”

“Were you locked in your room?” enquired Sir Richard.

“Oh no! I daresay I should have been if Aunt had guessed what I meant to do, but she would never think of such a thing.”

“Then—forgive my curiosity!—why did you climb out of the window?” asked Sir Richard.

“Oh, that was on account of Pug!” replied Pen sunnily.

“Pug?”

“Yes, a horrid little creature! He sleeps in a basket in the hall, and he always yaps if he thinks one is going out. That would have awakened Aunt Almeria. There was nothing else I could do.”

Sir Richard regarded her with a lurking smile. “Naturally not. Do you know, Pen, I owe you a debt of gratitude?”

“Oh?” she said, pleased, but doubtful. “Why?”

“I thought I knew your sex. I was wrong.”

“Oh!” she said again. “Do you mean that I don’t behave as a delicately bred female should?”

“That is one way of putting it, certainly.”

“It is the way Aunt Almeria puts it.”

“She would, of course.”

“I am afraid,” confessed Pen, “that I am not very well-behaved. Aunt says that I had a lamentable upbringing, because my father treated me as though I had been a boy. I ought to have been, you understand.”

“I cannot agree with you,” said Sir Richard. “As a boy you would have been in no way remarkable; as a female, believe me, you are unique.”

She flushed to the roots of her hair. “I think that is a compliment.”

“It is,” Sir Richard said, amused.

“Well, I wasn’t sure, because I am not out yet, and I do not know any men except my uncle and Fred, and they don’t pay compliments. That is to say, not like that.” She looked up rather shyly, but chancing to catch sight of someone through the window, suddenly exclaimed: “Why, there’s Mr Yarde!”

“Mr who?” asked Sir Richard, turning his head.

“You can’t see him now: he has gone past the window. You must remember Mr Yarde, sir! He was the odd little man who got into the coach at Chippenham, and used such queer words that I could not perfectly understand him. Do you suppose he can be coming to this inn?”

“I sincerely trust not!” said Sir Richard.

Chapter 5

His trust was soon seen to have been misplaced, for after a few minutes the landlord came into the room, to ask apologetically whether the noble gentleman would object to giving up one of his rooms to another traveller. “I told him as how your honour had bespoke both bedchambers, but he is very wishful to get a lodging, sir, so I told him as how I would ask your honour if, maybe, the young gentleman could share your honour’s chamber—there being two beds, sir.”

Sir Richard, meeting Miss Creed’s eye for one pregnant moment, saw that she was struggling with a strong desire to burst out laughing. His own lips quivered, but before he could answer the landlord, the sharp face of Mr Jimmy Yarde peered over that worthy’s shoulder.

Upon recognizing the occupants of the parlour, Mr Yarde seemed to be momentarily taken aback. He recovered himself quickly, however, to thrust his way into the parlour with a very fair assumption of delight at encountering two persons already known to him. “Well, if it ain’t my young chub!” he exclaimed. “Dang me if I didn’t think the pair of you had loped off to Wroxhall!”

“No,” said Sir Richard. “It appeared to me that Wroxhall would be over-full of travellers to-night.”

“Ay, you’re a damned knowing one, ain’t you? Knowed it the instant I clapped my glaziers on you. And right you are! Says I to myself, “Wroxhall’s no place for you, Jimmy, my boy!”“

“Was the thin woman still having the vapours?” asked Pen.

“Lordy, young chub, she were stretched out as stiff as a corpse when I loped off, and no one knowing what to do to bring her to her senses. Ah, and mighty peevy I thought myself, to hit on the notion of coming to this ken—not knowing as you had bespoke all the rooms afore me.”

His bright face shifted to Sir Richard’s unpromising countenance. “Unfortunate!” said Sir Richard politely.

“Ah, now!” wheedled Mr Yarde, “you wouldn’t go for to out-jockey Jimmy Yarde! Lordy, it’s all of eleven o’clock, and the light gone. What’s to stop your doubling up with the young shaver?”

“If your honour would condescend to allow the young gentleman to sleep in the spare bed in your honour’s chamber?” interpolated the landlord in an ingratiating tone.

“No,” said Sir Richard. “I am an extremely light sleeper, and my nephew snores.” Ignoring an indignant gasp from Pen, he turned to Mr Yarde. “Do you snore?” he asked.

Jimmy grinned. “Not me! I sleep like a baby, so help me!”

“Then you,” said Sir Richard, “may share my room.”

“Done!” said Jimmy promptly. “Spoke like a rare gager, guv’nor, which I knew you was. Damme, if I don’t drain a clank to your very good health!”

Resigning himself to the inevitable, Sir Richard nodded to the landlord, and bade Jimmy draw up a chair.

Not having boarded the stage-coach when Pen had announced Sir Richard to be her tutor, Jimmy apparently accepted her new relationship without question. He spoke of her to Sir Richard as “your nevvy,” drank both their healths in gin-and-water bespoken by Sir Richard, and seemed to be inclined to make a night of it. He became rather loquacious over his second glass of daffy, and made several mysterious references to Files, and those engaged on the Dub-lay, and the Kidd. Various embittered strictures on Flash Culls led Sir Richard to infer that he had lately been working in partnership with persons above his own social standing, and did not mean to repeat the experience.

Pen sat drinking it all in, with her eyes growing rounder and rounder, until Sir Richard said that it was time she was in bed. He escorted her out of the parlour to the foot of the stairs, where she whispered to him in the tone of one who has made a great discovery: “Dear sir, I don’t believe he is a respectable person!”

“No,” said Sir Richard. “I don’t believe it either.”

“But is he a thief?” asked Pen, shocked.

“I should think undoubtedly. Which is why you will lock your door, my child. Is it understood?”

“Yes, but are you sure you will be safe? It would be dreadful if he were to cut your throat in the night!”

“It would indeed,” Sir Richard agreed. “But I can assure you he won’t. You may take this for me, if you will, and keep it till the morning.”

He put his heavy purse into her hand. She nodded. “Yes, I will. You will take great care, will you not?”

“I promise,” he said, smiling. “Be off now, and don’t tease yourself over my safety!”

He went back to the parlour, where Jimmy Yarde awaited him. Being called upon to join Mr Yarde in a glass of daffy, he raised not the slightest objection, although he very soon suspected Jimmy of trying to drink him under the table. As he refilled the glasses for the third time, he said apologetically: “Perhaps I ought to warn you that I am accounted to have a reasonably strong head. I should not like you to waste your time, Mr Yarde.”

Jimmy was not at all abashed. He grinned, and said: “Ah, I said you was a peevy cull! Knowed it as soon as I clapped my daylights on to you. You learned to drink Blue Ruin in Cribb’s parlour!”

“Quite right,” said Sir Richard.

“Oh, I knowed it, bless your heart! “That there gentry-cove would peel remarkably well,” I says to myself. “And a handy bunch of fives he’s got.” Never you fret, guv’nor: Jimmy Yarde’s no green “un. What snabbles me, though, is how you come to be travelling in the common rumble.”

Sir Richard gave a soft laugh suddenly. “You see, I have lost all my money,” he said.

“Lost all your money?” repeated Jimmy, astonished.

“On “Change,” added Sir Richard.

The light, sharp eyes flickered over his elegant person. “Ah, you’re trying to gammon me! What’s the lay?”

“None at all.”

“Dang me if I ever met such a cursed rum touch!” A suspicion crossed his mind. “You ain’t killed your man, guv’nor?”

“No. Have you?”

Jimmy looked quite alarmed. “Not me, guv’nor, not me! I don’t hold with violence, any gait.”

Sir Richard helped himself to a leisurely pinch of snuff. “Just the Knuckle, eh?”

Jimmy gave a start, and looked at him with uneasy respect. “What would the likes of you know about the Knuckle?”

“Not very much, admittedly. I believe it means the filching of watches, snuff-boxes, and such-like from the pockets of the unsuspecting.”

“Here!” said Jimmy, looking very hard at him across the table, “you don’t work the Drop, do you?”

Sir Richard shook his head.

“You ain’t a Picker-up, or p’raps a Kidd?”

“No,” said Sir Richard. “I am quite honest—what you, I fancy, call a Flat.”

“I don’t!” Jimmy said emphatically. “I never met a flat what was so unaccountable knowing as what you are, guv’nor; and what’s more I hope I don’t meet one again!”

He watched Sir Richard rise to his feet, and kindle his bedroom candle at the guttering one on the table. He was frowning in a puzzled way, clearly uncertain in his mind. “Going to bed, guv’nor?”

Sir Richard glanced down at him. “Yes. I did warn you that I am a shockingly light sleeper, did I not?”

“Lord, you ain’t got no need to fear me!”

“I am quite sure I have not,” smiled Sir Richard.

When Jimmy Yarde, an hour later, softly tiptoed into the low-pitched bed-chamber above the parlour, Sir Richard lay to all appearances peacefully asleep. Jimmy edged close to the bed, and stood watching him, and listening to his even breathing.

“Don’t drop hot tallow on me, I beg!” said Sir Richard, not opening his eyes.

Jimmy Yarde jumped, and swore.

“Quite so,” said Sir Richard.

Jimmy Yarde cast him a look of venomous dislike, and in silence undressed, and got into the neighbouring bed.

He awoke at an early hour, to hear roosters crowing from farm to farm in the distance. The sun was up, but the day was still misty, and the air very, fresh. The bed creaked under him as he sat up, but it did not rouse Sir Richard. Jimmy Yarde slid out of it cautiously, and dressed himself. On the dimity-covered table by the window, Sir Richard’s gold quizzing-glass and snuff-box lay, carelessly discarded. Jimmy looked wistfully at him. He was something of a connoisseur in snuff-boxes, and his fingers itched to slip this one into his pocket. He glanced uncertainly towards the bed. Sir Richard sighed in his sleep. His coat hung over a chair within Jimmy’s reach. Keeping his eyes on Sir Richard, Jimmy felt in its pockets. Nothing but a handkerchief rewarded his search. But Sir Richard had given no sign of returning consciousness. Jimmy picked up the snuff-box, and inspected it. Still no movement from the bed. Emboldened, Jimmy dropped it into his capacious pocket. The quizzing-glass swiftly followed it. Jimmy went stealthily towards the door. As he reached it, a yawn made him halt in his tracks, and spin round.

Sir Richard stretched, and yawned again. “You’re up early, my friend,” he remarked.

“That’s right,” said Jimmy, anxious to be gone before his theft could be discovered. “I’m not one for lying abed on a fine summer’s morning. I’ll get a breath of air before I have my breakfast. Daresay we’ll meet downstairs, eh, guv’nor?”

“I dare say we shall,” agreed Sir Richard. “But in case we don’t, I’ll relieve you of my snuff-box and my eyeglass now.”

Exasperated, Jimmy let fall the modest bundle which contained his nightgear. “Dang me, if I ever met such a leery cove in all my puff!” he said. “You never saw me lift that lobb!”

“I warned you that I was a shockingly light sleeper,” said Sir Richard.

“Bubbled by a gudgeon!” said Jimmy disgustedly, handing over the booty. “Here you are: there’s no need for you to go calling in any harman, eh?”

“None at all,” replied Sir Richard.

“Damme, you’re a blood after my own fancy, guv’nor! No hard feeling?”

“Not the least in the world.”

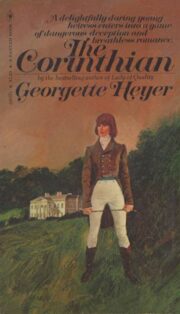

"The Corinthian" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Corinthian". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Corinthian" друзьям в соцсетях.