Lauren listened and nodded, but inside she felt restless, edgy. She didn’t want to be interested in this man. But she was. She told herself it was just her way. She was interested in people. She couldn’t help it.

The sun was high and hot and she was getting hungry and thirsty, but she still didn’t want to go back to the camp. She got stiffly to her feet and moved to the edge of the creek bank. The water slid by like liquid glass, so clear and clean she could see tiny tadpoles darting about in the shallows. She lowered herself gingerly, balanced on the balls of her feet, and let her fingers trail in the water. She shook them, then touched the cool moisture to her lips.

“Thirsty?” Bronco’s voice seemed very close.

She nodded. “Is it safe to drink?”

He gave a short laugh. “Is it polluted, you mean? Who knows? It’s never bothered me. I guess you take your chances.”

Lauren didn’t bother to answer. To her the water looked clean and she was thirsty. She cupped her hand and brought it to her lips, but got only a sip-most of the water wound up on her shirtfront.

“There’s two ways to do that,” came a lazy drawl from behind her. “You can stretch out on your belly and scoop one-handed, or you can use two hands-like this.”

Though the stubborn and childish part of her didn’t want to, she turned her head and watched him demonstrate, keeping her eyes on this hands. When he lifted them to his face, her eyes followed and she said seriously, “I thought I’d use your hat.”

Bronco’s laugh was short and sharp; she couldn’t account for the little sting of pleasure it gave her. “You do and you owe me a new hat.”

Her heart fluttered as she pretended surprise. “Come on-they do it in the movies all the time.”

“There’s a lot of things in the movies you won’t catch me doing,” he said dryly. “Jumping on a horse from the top of a building, for one. That’s just plain stupid-and the horse doesn’t like it much, either.”

He watched the smile that hovered over her lips as she turned away to hide it from him, just enough of one to make him think about how long it had been since he’d seen her really smile. And how beautiful she was when she did.

Regrets filled him-and then were forgotten as it occurred to him that she was pondering a small dilemma: How was she going to get herself a drink without showing him her backside? Basically, as he’d told her, she had two choices-she could stretch out flat on her belly, which was going to involve some complex maneuvering and result in her being altogether vulnerable; or she could lean way over from her present position on her knees and give him a view that made his mouth go dry just thinking about it.

To his undeniable delight, she chose the latter option. He knew he ought to look away-for the sake of common courtesy, as well as his own peace of mind-but he didn’t. Pretending complete lack of interest, he stretched himself out on his side with his elbow planted in the grass and his head resting on his hand and watched from under his eyelashes as blue denim stretched over her round firm bottom. The day suddenly got humid as a sweat lodge, and thunder grumbled in the pit of his stomach.

“Better not let my hat fall in that creek,” he drawled in a voice that sounded like a big daddy bullfrog.

She straightened up and sailed the hat back to him, then went back to dipping her hands in the creek. And this time there was almost defiance in the way she poked that bottom up in the air, as if she knew well and good what kind of effect it was likely to have on him, and was doing it to make him suffer.

Damn her. What he ought to do, he decided, was turn her over his knee and- Oh, Lord. Funny, he thought, how her boldness was just as much a turn-on to him now as her shyness had been earlier. Then again, maybe it wasn’t so strange, and the two were only different sides of the same thing-her awareness of him as a man. It was a dangerous notion. Intoxicating as peyote.

He was thinking he might need to take a quick dip in that creek, just to cool himself off.

Chapter 8

Her thirst quenched, Lauren straightened, smoothing water over her face and neck like oil. She gave Bronco a sideways look and said, “I’m curious. If you hated the U.S. Army so much for what they did to your ancestors, why did you join?”

Shoot, thought Bronco, if that wasn’t just like a lawyer. Ask him a question from a conversation so far back he could hardly remember it-probably just trying to trip him up. Erotic thoughts scattered like pollen on the wind, and as before, there was a part of him that felt disappointed at their going.

“I was young and stupid,” he snapped. Then, his irritation dissipating as quickly as it had come, he added philosophically, “And out of options.” He pushed himself to a sitting position and slapped his hat once on the leg of his Levis before he handed it back to her, along with a wry smile. “I was a pretty wild kid.”

“Gil said you had a problem with alcohol.” She pitched that at him boldly, then waited for his response.

He looked at her for a moment while he considered what it would be, and decided on a line drive up the middle. “Runs in the family,” he said evenly. “My old man was a drunk.”

If he’d hoped to shock her, he was disappointed. She fielded it with a nod, without even flinching. “Gil told me your dad was killed in an automobile accident.”

“Seems like Gil told you a lot of things about me.” He offered her the half smile again, sort of as a peace offering.

“I think he was trying to warn me off,” she said dryly, then threw him a quick glance and added before he could get in a smart remark, “Not that he needed to.”

Bronco gave a short huff of laughter and replied in a tone as sardonic as hers, deliberately misunderstanding which way she’d meant that remark. “Ol’ Gil looks out for me.”

He got to his feet and took his time stretching out his kinks so he wouldn’t have to look at her. “As far as my old man goes, the best thing you could say about him is at least he didn’t kill anybody besides himself.”

“I take it he’d been drinking?”

He nodded. “As always. His luck finally ran out. I was in…seventh grade, I guess.” He made a show of thinking about it. “Yeah, that’s right, because he’d have been my math teacher the following year.”

He expected Lauren to be surprised by that; he knew the kind of preconceived notions most people had about Indians. She didn’t let him down.

“Your dad was a teacher?”

He turned to find her squinting up at him, shading her eyes with one hand. Her skin had already dried to a rosy matte velvet that made him think of ripe peaches. “Both my parents were,” he said matter-of-factly.

Her careful exhalation was like a whisper barely heard. “So, your mother was a teacher, and she was-”

“From Portland, Maine,” he finished for her. “A fine old New England family-their name was Livingston, I believe. She was fresh out of college when she met my father-came out here to teach the poor little Indian children.” He wanted to look away but didn’t. Instead, he locked eyes with her and dared her to ask…

“What happened to her?”

As quiet as her voice was, he heard the quiver of emotion in it. And as carefully as he’d guarded against it, he felt an answering vibration begin in his own chest. This was dangerous ground, forbidden ground. In a way, sacred. And yet something in him acknowledged that he could have avoided going there if he’d truly wanted to.

He gave a shrug, a small one, just a slight dip of his head. “One day she left. Went back to Maine.”

“Just like that?” Her voice had gone hollow with her disbelief. “She just left you? Left her own child?”

Bronco nodded, still holding her gaze, giving no quarter. “When I was seven.”

“My God, why?” And he could hear the vibration in her voice growing stronger, giving him the impression that she was trembling.

Perhaps that was why-although he’d meant to laugh it off, to be flippant and smile-he frowned and said almost gently, “I wondered that myself-I think I might actually have asked her. I don’t remember what she said. My dad told me she was unhappy out here, that she missed her home and family back in Maine.” Now he did manage a smile, but there was nothing at all of humor in it. “But no matter what he said, I knew it must be my fault. I must have done something. I’d been a bad boy, or I wasn’t a good enough son, or-” he broke off when he heard Lauren’s small stricken gasp. “Hey,” he added softly, “I was seven years old. What can I say?”

He was good at hiding pain-he’d had a lot of years to get good at it. Plus, he had an ancestral reputation for stoicism to maintain. So why did he have the distinct feeling, one that grew stronger the longer she stared at him, that this woman wasn’t one bit fooled? Gazing back at her, he felt the years falling off him like worn-out clothes, until he was left to stand before her, naked as a newborn baby. And as vulnerable.

Fear crept into his heart, and like a cadre of vigilant militia forces, anger rushed to surround and vanquish the intruder, as it had rushed to his defense so many times in the past. He felt the familiar heat and turmoil rising inside him and slowly flexed his fingers and clenched them into fists, beginning the exercises that would take the anger away and send it to a safe and quiet place.

Then he heard Lauren’s voice, like a soft sweet wind. “Funny-” she murmured.

“What’s funny?” His voice was a snarl.

“Your mother-”

But that was as far as she got. Bronco’s body went rigid and still, and his hand shot out reflexively, motioning her to silence.

“What-”

“Stay there.”

Leaving his bewildered prisoner crouched in the grass, he moved swiftly to higher ground-a mound of gravelly debris washed down by monsoon cloudbursts from the rocky point that stood between them and the main camp. From there he could see what his ears had already forecast: three all-terrain vehicles rocking and jouncing across the meadow toward the main gate, leaving faint dust plumes and the snarl of engines behind. He shaded his eyes with his hand, trying to see who was leaving in such a great hurry, but he was too far away to tell with any certainty. Nevertheless, he was sure Ron Masters was one.

All traces of anger, fear and vulnerability had vanished. His mind felt calm and quiet.

It would happen soon. When it did, he must be ready.

“What’s happening out there? Talk to me, man, talk to me.” Rhett Brown’s hand gripped the telephone receiver so hard Dixie wondered that the plastic didn’t crack under the strain.

He’d been waiting for word-any word-pacing like a caged animal. She’d never seen him like that before. And yet she understood. It was the helplessness-that was the worst part. The feeling of being utterly and completely powerless. How ironic it was, she thought, that a man possibly destined to become the most powerful man on earth should be reduced to such a state.

He was listening now, his body tense, face set in gaunt lines that betrayed all the fear and strain and uncertainty of the past few days. As he listened he put out his arm, and Dixie moved out of old habit into its comforting shelter. She put her arms around him and pressed her face against his shoulder, and her heart ached when she felt his body tremble.

“My God-” his voice cracked “-how could you let this happen?”

Then he listened again for a long time, offering only monosyllables himself and those in leaden tones, while Dixie waited with her hand against his thumping heart, her body as rigid as his and every nerve vibrating with suspense.

It seemed to her half a lifetime before Rhett placed the receiver back in its cradle. It took him two tries.

“Bad news?” she whispered, cold inside. Numb with dread.

“There’s been a shooting.” He was staring past her out the window, squinting hard as if there was something out there of great interest to him, but he couldn’t quite make it out. “At McCullough’s Ranch.”

Dixie’s eyes were locked on her husband’s face. “Not-”

His head moved-one quick, hard shake. “No, not Lau ren.” His arms encircled her and pulled her close so that she heard the rest as a whisper of exhaled breath. “Not Lauren…”

“Rhett, what happened?”

It was a while before he answered her. In the quietness she heard the busy chick-chick-chick of the sprinklers in the horse pastures, the haunting cry of a mourning dove from somewhere down in the river bottom and the high-pitched whinny of a colt calling to its mother out in the paddocks. She was glad they were here; it was always so peaceful on the Tipsy Pee, and she knew Rhett found some comfort in being here in Texas, that much closer to the last place his daughter had been seen alive, in the last place she’d called home, before…

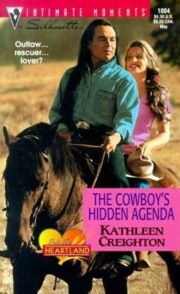

"The Cowboy’s Hidden Agenda" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Cowboy’s Hidden Agenda". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Cowboy’s Hidden Agenda" друзьям в соцсетях.