"Not everyone is as special as you, Grandma," I said politely. "Oh, look, it's my stop. I have to go."

"Jay will call you!" trilled Grandma.

"I've heard that one before," I muttered, but Grandma had already rung off. Undoubtedly to phone Mitten, or Muffin, or whatever her name was, and break out the celebratory champagne.

Grandma had been trying to marry me off, by one means or another, since I'd hit puberty. I kept hoping that, eventually, she would give up on me and switch her attention to my little sister, who, at the age of nineteen, was dangerously close to spinster-hood by Grandma's standards. So far, though, Grandma stubbornly refused to be rerouted, much to Jillian's relief. I would have admired her tenacity if it hadn't been directed at me.

I hadn't been entirely lying about it being my stop; the bus, imitating the tortoise in the old fable, was slowly inching its way past Euston station, which meant that I would be the next stop up, across the street from one of the plethora of Pizza Expresses that dotted the London landscape like glass-fronted mushrooms.

I stuffed my phone back in my bag and began the torturous process of navigating the narrow stairs down from the upper level of the bus, consoling myself with the thought that with any luck, this Jay-from-Birmingham would be as reluctant as I was to go on a family-assisted setup. I could think of few things more ghastly than sitting across the table from someone with whom the only thing I had in common was that my grandmother shared a beauty parlor with his mother. Anyone who had seen Grandma's hair would agree.

Swinging myself off the bus, I scurried through the massive iron gates that front the courtyard of the British Library. The pigeons, bloated with the lunchtime leavings of scholars and tourists, cast me baleful glances from their beady black eyes as I wove around them, making for the automatic doors at the entrance. It was early enough that there was a mere straggle of tourists lined up in front of the coat check in the basement.

Feeling superior, I made straight for the table on the other side of the room, transferring the day's essentials from my computer bag into one of the sturdy bags of clear plastic provided for researchers: laptop for transcribing documents; notebook in case the laptop broke down; pencils, ditto; mobile, for compulsive checking during lunch and bathroom breaks; wallet, for the buying of lunch; and a novel, carefully hidden between laptop and notebook, for propping up at the edge of my tray during lunchtime. The bag began to sag ominously.

I could see the point of the plastic bags as a means of preventing hardened document thieves from slipping out with a scrap of Dickens's correspondence, but it had a decidedly dampening effect on my choice of lunchtime reading material. And it was sheer hell smuggling in tampons.

Toting my bulging load, I made my way up in the elevator, past the brightly colored chairs in the mezzanine cafй, past the dispirited beige of the lunchroom, up to the third floor, where the ceilings were lower and tourists feared to tread. Perhaps "fear" was the wrong word; I couldn't imagine that they would want to.

Flashing my ID at the guard on duty at the desk in the manuscripts room, I dumped my loot on my favorite desk, earning a glare from a person studying an illuminated medieval manuscript three desks down. I smiled apologetically and insincerely, and began systematically unpacking my computer, computer cord, adapter, notebook, arraying them around the raised foam manuscript stand in the center of the desk with the ease of long practice. I'd done this so many times that I had the routine down. Computer to the right, angled in so the person next to me couldn't peek; notebook to the left, pencil neatly resting on top; bag with phone, wallet, and incriminating leisure fiction shoved as far beneath the desk as it could go, but not so far that I couldn't occasionally make the plastic crinkle with my foot to make sure it was still there and some intrepid purse snatcher disguised as a researcher hadn't crawled underneath and made off with my lunch money.

Having staked out my desk, I made for the computer station at the front of the room. I might know who the Pink Carnation was, but I stood a better chance of making my case to a skeptical academic audience if I could definitively link many, if not all, of the Pink Carnation's recorded exploits to Miss Jane Wooliston. After all, just because Jane had started out as the Pink Carnation didn't mean she had remained in possession of the title. What if, like the Dread Pirate Roberts, she had handed the name off to someone else? I didn't think so—having worked with several of Jane's letters, I couldn't imagine anyone else being able to muster quite the same combination of rigorous logic and reckless daring—but it was the sort of objection someone was sure to propound. At great length. With lots of footnotes.

I needed footnotes of my own to counteract that. It was the usual sort of academic battle: footnotes at ten paces, bolstered by snide articles in academic journals and lots of sniping about methodology, a thrust and parry of source and countersource. My sources had to be better.

From my little dip into Colin's library that past weekend, I had learned that Jane had been sent to Ireland to deal with the threat of an uprising against British rule egged on by France in the hopes that, with Ireland in disarray, England would prove an easy target. Ten points to me, since one of the daring exploits with which the Pink Carnation was credited was quelling the Irish rebellion of 1803. But I didn't know anything beyond that. I didn't have any proof that Jane was actually there. In the official histories, the failure of the rebellion tended to be attributed to a more mundane series of mistakes and misfortunes, rather than the agency of any one person.

According to the Selwick documents, Jane wasn't the only one to be dispatched to Ireland. Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe, who had served as second in command of the League of the Purple Gentian, had also received his marching orders from the War Office. A search for Jane's name in the records of the British Library was sure to yield nothing, but what if I looked for Lord Pinchingdale? Ever since reading the papers at Mrs. Selwick-Alderly's flat, I'd been meaning to look into Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe, anyway, if only to add more footnotes to my dissertation chapter on the internal workings of the League of the Purple Gentian.

I hadn't had a chance to pursue that angle because I had gone straight off to Sussex.

With Colin.

The agitated bleep of the computer as I accidentally leaned on one of the keys didn't do anything to make me popular with the other researchers, but it did bring me back from the remoter realms of daydream.

Right. I straightened up and purposefully punched in "Pinchingdale-Snipe." Nothing. Ah, dйjа vu. Futile archive searches had been my way of life for a very long time before I had the good fortune to stumble across the Selwicks. Clearly, I hadn't lost the knack of it. Getting back into gear, I tried just plain "Pinchingdale." Four hits! Unfortunately, three of them were treatises on botany by an eighteenth-century Pinchingdale with a horticultural bent, and one the correspondence of a Sir Marmaduke Pinchingdale, who was two hundred years too early for me, in addition to being decidedly not a Geoffrey. There was no way anyone could confuse those two names, not even with very bad spelling and even worse handwriting.

The logical thing to do would have been to call Mrs. Selwick-Alderly, Colin's aunt. Even if the materials I was looking for weren't in her private collection, she would likely have a good notion of where I should start. But to call Mrs. Selwick-Alderly veered dangerously close to calling Colin. Really, could there be anything more pathetic than looking for excuses to call his relations and fish for information about his whereabouts? I refused to be That Girl.

Of course, that begged the question of whether it was any less pathetic to check my phone for messages every five minutes.

Preferring not to pursue that line of thought, I stared blankly at the computer screen. It stared equally blankly back at me. Behind me, I could hear the subtle brush of fabric that meant someone was shuffling his feet against the carpet in a passive-aggressive attempt to communicate that he was waiting to use the terminal. Damn.

On a whim, I tapped out the name "Alsworthy," just to show that I was still doing something and not uselessly frittering away valuable computer time. From what I had read in the Selwick collection, Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe had been ridiculously besotted with a woman named Mary Alsworthy—although none of his friends seemed to think terribly much of her. The words "shallow flirt" had come up more than once. Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe's indiscretion might be my good fortune. In the throes of infatuation, wasn't it only logical that a man might reveal a little more than he ought? Especially over the course of a separation? If the War Office was sending Lord Pinchingdale off to Ireland, it made sense that he would continue to correspond with his beloved. And in the course of that correspondence…

Buoyed by my own theory, I scrolled down through a long list of Victorian Alsworthys, World War I Alsworthys, Alsworthys from every conceivable time period. For crying out loud, you'd think their name was Smith. The foot-shuffling man behind me gave up on shuffling and upped the level of unspoken aggression by conspicuously flipping through the ancient volumes of paper catalogs next to me. I was too busy scanning dates to feel guilty. Alsworthys, Alsworthys everywhere, and not a one of any use to me.

Or maybe not. My hand stilled on the scroll button as the dates 1784–1863 flashed by. I quickly scrolled back up, clumsily engaging in mental math. Take 1784 away from 1803…and you got eighteen. Um, I meant nineteen. This is why my checkbook never balances. Either way, it was an eminently appropriate age for an English debutante in London for the Season.

There was only one slight hitch. The name beside the dates wasn't Mary. It was Laetitia.

That, I assured myself rapidly, scribbling down the call number, didn't necessarily mean anything. After all, my friend Pammy's real first name was Alexandra, but she had gone by her middle name, Pamela, ever since we were in kindergarten, largely because her mother was an Alexandra, too, and it created all sorts of confusion. Forget all that rose-by-another-name rubbish. Pammy had been Pammy for so long that it was impossible to imagine her as anything else.

Behind me, the foot-shuffling man claimed my vacant seat with an air of barely restrained triumph. Prolonged exposure to the Manuscript Room does sad, sad things to some people.

I handed in my call slip to the man behind the desk and retreated to my own square of territory, nudging my plastic bag with my foot to make sure everything was still there. Between Mary and Laetitia…well, I would have chosen to be called Laetitia, but there was no accounting for taste. Maybe she got sick of dealing with variant spellings.

Except…I scowled at my empty manuscript stand. There was a Laetitia Alsworthy. Just to make sure, I scooted my computer to a more comfortable angle, and opened up the file into which I had transcribed my notes from Sussex. Sure enough, there it was. One Letty Alsworthy, who appeared to be friends with Lady Henrietta Selwick. Not close friends, I clarified for myself, squinting at my transcription of Lady Henrietta's account of her ballroom activities in the summer of 1803, but the sort of second-or third-tier friend you're always pleased to run into, have good chats with, and keep meaning to get to know better if only you had the time. I had a bunch of those in college. And, in its own way, the London Season wasn't all that different from college, minus the classes. You had a set group of people, all revolving among the same events, with a smattering of culture masking more primal purposes, i.e., men trying to get women into bed, and women trying to get men to commit. Yep, I decided, just like college.

Pleased as I was with my little insight, that didn't solve the problem that Letty was a real, live human being with an independent existence from her sister Mary. Her sister Mary who might have corresponded with Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe.

I should have known that Mary wouldn't be the writing type.

Behind me, the little trolley used to transport books from the bowels of the British Library to the wraiths who haunted the reading room rolled to a stop. Checking the number on the slip against the number on my desk, the library attendant handed me a thick folio volume, bound in fading cardboard, that had seen its heyday sometime before Edward VIII ran off with Mrs. Simpson.

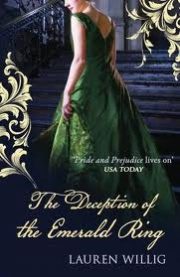

"The Deception of the Emerald Ring" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring" друзьям в соцсетях.