"No," Jasper croaked.

"Good." Geoff made no move to release his cousin's arm. "I'm glad we had this little talk. And now, dear cousin, I believe you are decidedly de trop."

Letty realized what Geoff was planning a moment before Jasper did. With a seemingly effortless movement, Geoff took his cousin by the scruff of his pants and swung him over the side of the wagon, right into the gutter. Jasper landed with a splash, cursing with enough vehemence to assure the onlookers that he was more outraged than injured.

Picking himself up, and flicking bits of refuse off his person, Jasper cast a malevolent glare over his shoulder at a pair of small children, who pointed and laughed.

"Good-bye, Jasper," called Geoff. "Don't forget to write your mother from India."

Jasper didn't bother to respond. Aiming a kick at a small dog who was exploring a tasty morsel that had attached itself to his boot, Jasper limped away, radiating indignation and refuse.

Wiping off his hands, Geoff glanced over his shoulder at Letty. "I should have done that years ago."

Letty would have liked to run to Geoff, to fling her arms around him, to cover his face with kisses, but the force of long habit held her back. That, and the echo of Jasper's jeering voice, pointing out just how much Geoff had wanted to marry another. Her own sister, in fact. Jasper was Jasper—and currently covered with muck—but that didn't change the fundamental truth of his assertions.

Clambering awkwardly down from the box, she joined Geoff in the wagon bed. Standing next to him, near enough that her sleeve brushed his, she watched Jasper's retreating form.

"Did you have to drop him on the softer side?"

"He is my cousin."

"He's a murderous swine," countered Letty stoutly.

Geoff looked down at her, a slight smile playing around his lips. "That, too."

That smile made Letty distinctly nervous. She took a half step back, skidding a bit in the straw. "If he had succeeded, you could have been free."

Geoff reached out to steady her, his hands cupping her elbows.

"I don't want to be free," he said.

Letty's eyes searched his face for some sign of reservations, something held back. "Not in that way, you mean?"

Geoff's hands tightened on her arms. "Not at all."

Letty bit her lip. Of course, he would say that. How could he say otherwise, without making himself complicit in her attempted murder? After all, she was his responsibility, and he was bound to protect her, whether he liked it or not.

Letty knew she should just let it drop, accept his avowal in the spirit in which it was offered, and go on home, to a bath, to a debriefing, to normal life. But she was sick of being a responsibility, and she was sick of polite platitudes.

"What about Mary?" she pressed on, lifting her bruised face earnestly toward his. "It's Mary that you want, that you've always wanted. I'm not Mary—I couldn't be Mary if I tried."

"No, you couldn't," agreed Geoff, his hands sliding up her arms. "I wouldn't want you to be. You're far more precious as you are."

Letty shook her head, mutely rejecting the compliment.

"I want you," Geoff said, his eyes intent on her face in a way that made Letty feel curiously bare, all the machinery of her mind, all her thoughts and emotions, his for the taking. "Not Mary. You."

"You don't have to say that," remonstrated Letty, putting a hand against his chest to ward off further words. "I know you're trying to be kind, but—" How could she explain that it was far crueler to raise hopes that couldn't possibly be realized?

"Kind?" Comprehension kindled in Geoff's gray eyes. His lips twisted in exasperated fondness. "I'm not being kind. Mary was—" Pausing, Geoff groped for an explanation, his expression abstracted. "Mary was a young man's dream."

That was supposed to make her feel better?

Looking back down at Letty, Geoff searched for the correct words to make her understand. "Mary was a storybook illustration, a stained-glass window, an Orthodox icon. She was never real. Not like you."

"Imperfect, you mean," translated Letty.

A sudden smile transformed Geoff's thin face. "In the best of all possible ways."

Letty's nose wrinkled skeptically. "I don't think 'best' and 'imperfect' keep much company together."

"That's where you're wrong. Perfection may be admirable, but it's not very lovable."

Letty's disbelief must have shown on her face, because Geoff repeated, "Yes, lovable. I love the way all your thoughts show on your face—yes, just like that one. I love the way your hair won't stay where it's put. I love the way you wrinkle your nose when you're trying to think of something to say. I love your habit of plain speaking." He touched a finger to her nose. "And, yes, I even love your freckles. I wouldn't eliminate a single one of them, not for all the lemons in the world. There. Does that convince you?"

"You're mad," said Letty, exhibiting that laudable habit of plain speaking he so admired. "You must have hit your head. No, wait, I hit my head. That must be it. This can't be real. Not me. Not you. Not—" Letty shook her head. "No."

"Why?"

"It's too ridiculous to even contemplate. Like a fairy tale. Everyone knows the prince would never really fall in love with the beggar girl. Not in real life. The prince falls in love with the princess, and they go on living in their gilded hall, with their gilded children, in their gilded chairs."

Geoff held up his hands, spreading open his fingers. "I seem to be entirely out of gold leaf at present."

Letty shook her head, brushing away his remark.

"I used to watch you with Mary," she confessed. "I used to watch you with Mary and wish it were me."

She had never admitted it, even to herself, but it was horribly, miserably true. She had hidden it behind a screen of self-righteous judgment, telling herself it was merely that they weren't suited, or that she disapproved of Mary's methods, but that wasn't the real reason. That had never been the real reason.

She had no right to judge anyone, not her sister, not Geoff, not anyone. Not when she had channeled jealousy into spite and pretended it was for their own good. She couldn't even say with any surety that her motives for barging into their elopement were entirely pure. Guilt rose in her, like bile at the back of her throat, tainting everything it touched. That night, if she had left them alone, if she had stayed in her room, Mary would have gone off with Geoff and they would have lived happily ever after. The family reputation certainly couldn't have been more tarnished than it had been by her.

But she had interfered—not out of a pure, disinterested desire for the good of the family, but because, in a hidden little recess in the back of her heart, she had wanted Lord Pinchingdale for herself. And she had known she could never have him.

It wasn't a pleasant realization, any of it. Those people who lauded self-knowledge had clearly never tried it.

"I knew that even if she weren't there—" Letty broke off with an unhappy little laugh. "It was useless. I might as well cry for the moon. You were that far above my touch."

Geoff's brows drew together in confusion.

"Because of the title?" he asked incredulously.

For a smart man, at times he really could be very slow. The thought almost made Letty smile. Almost.

"No. Because you're you. Clever and subtle and cultured…" Letty waved her hands about in wordless illustration. "And I'm just plain old Letty from Hertfordshire."

Geoff's lips quirked. "Nineteen is hardly old. And if you're from Hertfordshire, so is your sister."

"Yes, but with Mary, it didn't stick. She looks right in a London ballroom; I don't. Your house makes me feel like King Cophetua's beggar maid."

Geoff tucked a flyaway wisp of hair back behind her ear. "You can redecorate."

"No," Letty protested, pushing irritably away. "That's not it at all."

It might be rather self-defeating to list for him all the reasons he shouldn't love her, but better that than to have him profess sentiments he couldn't really mean, that couldn't possibly survive once they left the enchanted green world of Ireland and returned to the overheated drawing rooms of London, where the spiteful whispers of their so-called friends would peck holes into any pretensions of affection he might have for her. They would return, and he would realize that she was nothing but a dowdy duckling, a glorified goose girl, stout and sturdy and utterly mundane.

Letty redoubled her efforts. "You don't understand. I'll never be sophisticated or graceful or have poems written to me. I'm not the sort of person you want at all."

Looking down into Letty's flushed face, Geoff said matter- of-factly, "Don't you think I should be the judge of that? As clever and sophisticated and whatnot as I am? Besides," he added, when Letty looked like she was about to remonstrate, "I'm not all that comfortable in a ballroom myself. And I've never had a single poem written to me. Unless you want to volunteer. Your poetic efforts could hardly be worse than mine."

Letty narrowed her eyes at him. "But you always seem so assured. So polished."

"You mean, so quiet," Geoff countered.

He waited a moment, watching her, allowing time for his words to sink in. Letty cast her memory back over the hundreds of times she had encountered him over the course of the Season, since his return from France. Her memory conjured him standing with his friends at the side of the room, leaning over Mary's chair, propping up the wall at a musicale. In every image, he was watching, observing, somewhere off on the fringes while other people laughed and danced.

"Oh," said Letty stupidly.

"I've always been more comfortable with books than people. Running off to France for years made the problem easy to avoid."

Letty felt a bit as though she had spent hours squinting at a book, trying desperately to read it, and someone had just come along and turned it right-side up. She knew, logically, this was the proper way to look at it, but her unfocused eyes were having trouble registering the words.

"So, when you came back…"

"I felt just as out of place as you did. So I attached myself to your sister. She made a convenient altar at which to worship. It gave me a place and a purpose, where I otherwise had none." Remembering, Geoff stared off into the air above Letty's left shoulder, lips pressed together in an uncompromising line. "I misused her badly, although that was never my intention at the time."

"No," said Letty slowly. "Of course not."

Was he saying—he did seem to be saying—that he had never really loved Mary? He couldn't mean that. His devotion to Mary had become a commonplace, like Petrarch's love for Laura or Dante's for Beatrice, a yardstick by which devotion was measured.

But it was all, Letty realized, devotion from a distance, worship from afar. She had always had her doubts as to whether Petrarch loved Laura. How could he, when he didn't know what Laura liked for breakfast, or whether she broke out in spots once a month, or had an unfortunate tendency to giggle at awkward moments?

In short, whether she was real. Letty's eyes lifted to Geoff's with new understanding, taking in the familiar features in a new way. The small lines around his gray eyes, the patient set of his mouth, the thoughtful furrow of his brow, all little imperfections that had drawn her to him from the first.

"I'm not your gilded prince with the gilded chairs, Letty," Geoff said simply. "I couldn't be if I tried."

"I wouldn't want you to be." Letty's voice felt rusty.

"I'm not particularly bold or dashing or heroic. I'm happier at my desk than in a black cloak. And I've never entirely mastered all the steps of the quadrille." He looked soberly down at her. "But what I am is yours, if you'll still have me."

It was a gesture more eloquent than a bended knee.

Somehow, Letty realized, he had turned the tables. He had taken all of her imperfections and turned them into his. He had turned his own pride inside out and offered it to her, hilt first, like a knight surrendering his sword, placing the power of refusal in her hands.

Letty was humbled by the very generosity of it. Humbled, and so filled with love that she could scarcely find the breath to express it. She didn't care if he couldn't dance the quadrille; she had no use for black cloaks; and she didn't mind if he preferred books to people so long as there was room among his books for her.

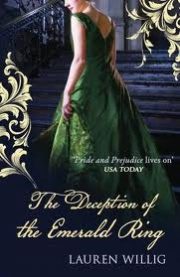

"The Deception of the Emerald Ring" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Deception of the Emerald Ring" друзьям в соцсетях.