“There was someone else,” I said.

“And you couldn’t marry him?”

I shook my head. My father was struggling with his principles and his love for his daughter. It was a great shock to him that I should have an illegitimate child. I felt I owed him some explanation for I did not want him to think I had been blithely immoral with no thought to consequences.

I said quietly: “It was forced on me.”

“Forced! My dear child!”

“Please … do you mind if we don’t talk about it.”

“Of course we won’t,” Clare said.

“Kendal dear, Kate is happy now .. whatever happened. And she’s successful with her work. That must be a great compensation for everything. And the little boy is such a darling.”

“Thank you, Clare,” I said.

“Perhaps I’ll be able to tell you later.

This has come so suddenly. “

“We should have told you we were on our way,” said Clare.

“We wanted it to be a surprise.”

“It’s a wonderful surprise. I’m so happy to see you. It is just that ”

“We understand,” said Clare.

“You will tell us when you want to. In the meantime, it is not our business. You have this studio and all this success. It is what you dreamed of, isn’t it?”

My father was looking in my direction as though he had been confronted by a stranger. I went to him and taking his hand kissed it.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“It’s been unfair to you. Perhaps I should have told you. I didn’t want to make difficulties. Believe me, it was not my fault. It… happened to me.”

“You mean … ?”

“Please don’t talk of it. Perhaps later. Not now. Oh, Father, I am so glad you are happy and that you have Clare.”

“Clare has been very good to me.”

I reached for her hand and we all stood close together.

“Please understand,” I said.

“I did not seek it. It … happened. I have a wonderful friend in Nicole who has smoothed the way for me. I believe that in spite of it I have been lucky.”

My father clenched his hand and said softly: “Was it that man… that Baron?”

“Father, please … it’s over and done with.”

“He did a lot for you. So it was because-‘ ” No, no. That’s quite wrong. Perhaps I can talk to you later. not now. “

“Kendal dear,” said Clare gently, ‘don’t distress Kate. Imagine all she has gone through. and then our coming so suddenly. She’ll tell us when she’s ready. Oh, Kate, it is wonderful to see you. Is the little boy interested in painting? “

“Yes, I really think he is going to be. He daubs a bit but I’m sure he has an eye for colour. I named him Kendal.. just in case.”

My father smiled gently. He gripped my hand tightly.

“You should have come to me, Kate,” he said.

“It was my place to help you.”

“I almost did. I might have done if Nicole hadn’t been there. Oh, Father, you have been so lucky to have Clare. I’ve been lucky with Nicole. It is a wonderful thing to have staunch friends.”

“I agree on that. I want to see the boy, Kate.”

"You shall. “

He murmured: “Kendal Collison. He’ll carry the torch perhaps.”

My father and Clare stayed with us for three days.

Once he had recovered from the shock, my father accepted my position in much the same way as he had accepted his oncoming blindness.

He did not ask any more intimate questions. Whether he presumed that I had actually been forced to submit to the Baron or whether he thought he had overpowered me with his persuasion, he did not ask and I did not tell him. He realized that talking of the matter distressed me and he wanted the visit to be a happy one. He wanted to stress the fact -which I already knew-that whatever happened to either of us our love for each other would remain as steady as a rock.

They talked of village matters. Hope had a little baby and was happy although for a long time she had been unable to get over her sister’s death. Everything was the same at the vicarage. Frances Meadows was a wonderful worker and managed the household efficiently as well as countless village concerns.

“Life is very quiet for us compared with you in your wonderful salon,” said Clare.

“But it suits us very well.”

My father’s sight had grown much worse. He did not wear glasses because they made no difference. I thought the time must come when he would be totally blind. I dreaded that day and I know he did.

Clare had long talks with me.

“He is adjusting himself gradually,” she said.

“I read to him. He loves that. Of course he can’t paint at all now. It’s heartbreaking to see him in the studio. He goes up there quite often still. I think your success means a great deal to him.”

“Clare,” I told her, “I don’t know how to be grateful enough to you.”

“It’s I who should be grateful. Before I came to you, life was so empty. Now it is full of meaning. I think I was meant to look after people.”

“It’s a very noble mission in life.”

“Your father is so kind … so good, I’m the lucky one. I am so sorry for people who haven’t had my luck. I often grieve for poor Faith Camborne.”

“She was always so helpless,” I said.

“I know. I tried to befriend her. I did what I could …”

“You were always very helpful to her and I know she was very fond of you.”

“All we can do now is pray that Hope will stop grieving for her sister and enjoy what life has given her … a good husband and a lovely baby.”

“Dear Clare,” I murmured, kissing her, Kendal was very excited to find he had a grandfather. He climbed all over him and peered into his face. He must have heard talk of his very imminent blindness because one day he climbed onto his knees and looking long into his face said:

“How are your poor eyes today?”

My father was so moved that he was almost in tears.

“I’ll see for you,” Kendal said.

“I’ll hold your hand all the time and won’t let you fall over.”

And when I saw the expression on my father’s face I could only rejoice once more in my boy and regret nothing just nothing-that had given him to me.

They were going on to Italy. My father wanted Clare to see those works of art which had affected him so deeply when he had had eyes to see them. I believed he would see them again through Clare.

She was so gentle with him, so kind, not fussing too much but just enough to let him know how much she cared for him, letting him do what he could for himself and yet at the same time always being there if he should need help.

I felt glad that they had come. It was as though a great weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I no longer had a dark secret which must be withheld from them. I should be able to write to them freely in future.

“Please, Clare,” I said when they left, “You must come and see me often. It is difficult for me to come to Farringdon, but do come again soon.”

They promised that they would.

Two years had passed. Kendal was now approaching his fifth birthday.

He could draw very well and there was nothing he liked better than to come to the studio in the afternoons when there were no clients there and sit at a bench and paint. He painted the statues he had seen in his favourite Luxembourg Gardens. Chopin particularly delighted him but he did some recognizable pictures of Watteau, Delacroix and Georges Sand. He had a skill which I thought was miraculous. I was writing to my father regularly for he was always wanting news of Kendal and was delighted to hear of his interest in painting; he wrote that at five years old I had begun to show such leanings.

“It is wonderful,” wrote my father, ‘to know that the link is not broken. “

He and Clare came to Paris twice during that period.

He was almost blind now and his writing was becoming difficult to decipher. Clare often wrote in his place. She told me that the decline in his sight, though gradual, was definite. However, he had accepted it and was very happy to talk with her, and she was reading to him more and more. He was up to date with the news and always liked to learn what was happening in France.

“I don’t read to him anything that I think might distress him,” she wrote.

“He did get a little uneasy about the situation over there.

There seems to be a certain dissatisfaction with the Emperor and with the Empress. She is beautiful, I know, but we hear that she is extravagant and then of course she is Spanish and the French always did dislike foreigners. Look how they hated Marie Antoinette. I think your father is always a little anxious that what happened eighty years ago will start all over again. “

I didn’t take much notice of that when I read it. Life in Paris was so pleasant. We had our soirees where beautiful and intelligent people congregated. We talked art more than politics, but I did notice that the latter were beginning to come more and more into the conversation.

Nicole was delighted with life, I think. She lived luxuriously and loved her soirees. I think now and then she took a lover, but there was no really serious relationship. I did not enquire and she did not tell me. I think in her heart she was always aware of what she called my Anglo-Saxon respectability, and she wanted nothing disturbed.

I was not without my admirers. I had never been beautiful but I had acquired something during my years with Nicole. A poise, I suppose. My work was highly successful and I was treated with great respect. It was considered a symbol of social rank to have a Collison miniature, and with the perversity of fashion, my sex, which had been a drawback, now became an asset.

I liked some of the men who made approaches to me, but I could never enter into an intimate relationship. As soon as they showed any signs of familiarity my whole being would shrink and I would see that face leering at me. It had become more and more like the demon-gargoyle of Notre Dame as the years passed.

We were all very happy. I engaged a nursery governess for Kendal. I could not expect Nicole to take him out every day although she liked to on occasions. Jeanne Colet was an excellent woman, kind yet firm.

She was just what Kendal needed. He took to her immediately. He was a very lovable child. He was mischievous occasionally as most children are, but there was always an absence of malice in his mischief. He wanted to find out how things worked and that was why he destroyed them sometimes. It was never due to a desire to spoil.

I suppose I saw him as perfect; but it was a fact that others loved him on sight, and he was a favourite wherever he went. Even the grim concierge came out to see him as he passed in and out. He used to run in and tell me about the people he had met in the Gardens. He spoke a mixture of French and English which was enchanting and perhaps one of his attractions.

However, people noticed him and perhaps that was why when he came back and talked about the gentleman in the gardens I did not at first pay much attention.

There was a fashion at that time for kites. The children flew them in the Gardens every day. Kendal had a beautiful one with the oriflamme the ancient banner of France emblazoned across it. The gold flames on a scarlet background were most effective and it certainly looked very splendid flying up in the sky.

He used to take the kite into the Gardens every morning and he would come back and tell me how high it had flown far beyond the other kites. He had thought it was going to fly right to England to see his grandfather.

Then one day he came back without his kite. He was in tears.

He said: “It flew away.”

“How did you let it do that?”

“The man was showing me how to fly it higher.”

“What man?”

“The man in the Gardens.”

I looked at Jeanne.

“Oh, it’s a gentleman,” she said.

“He’s sometimes there. He sits and watches the children play. He often has a word for Kendal.”

I said to Kendal: “Never mind. We’ll get you another kite.”

“It won’t be my oriflamme.”

“I expect we can find another somewhere,” I assured him.

The next morning he went offkiteless and rather disconsolate.

“I expect it’s with my grandfather by now,” he said, and that seemed to comfort him. Then he said anxiously: “Will he be able to see it?”

His face puckered a little and he showed more than sorrow for the loss of his kite. He was thinking of how his poor grandfather would not be able to see that glorious emblem. It was that thoughtfulness, that feeling for others, which made Kendal so endearing.

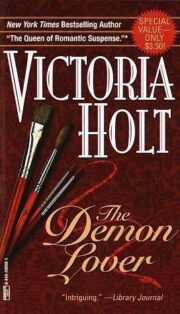

"The Demon Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Demon Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Demon Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.