“There’s a moral in it.”

“What’s that?”

“The wicked never prosper.”

He laughed and I stood up. He stood beside me. I had forgotten how big he was, how overpowering.

“I’d like to have a chance to put my case to you,” he said.

“May I?”

“No,” I answered.

“I am not interested in your case. I can only see you as a barbarian, a savage born out of your century. If you would please me … and God knows you owe me something … you will stay out of my life. Leave me with what I have suffered for and worked for.

These things belong to me and you have no part in them. ” I called:

“Kendal. Bring down the oriflamme. It’s time to go home.”

The Baron went to the boy and helped him with the kite. Kendal was leaping round with excitement while the Baron handed him the kite.

“Thank you for it,” said Kendal.

“It’s the best and biggest kite that was ever in the sky.”

I thought: Already he is making my son like him.

We made our way silently home. I was deeply apprehensive. I had not felt such fear for a long time.

Kendal walked soberly beside me, carefully carrying his oriflamme kite.

Paris under Siege

The peaceful days were over. I was now beset by anxiety because that man had come back into my life.

I talked it over with Nicole. She thought I was worrying unduly.

“Naturally he’s interested in his own son,” she said.

“He just wants to see him and the best way of doing this, as you would not welcome him here, is in the Gardens. What harm is he doing?”

“I know that wherever he is there will be harm. What can I do?”

“Nothing,” replied Nicole calmly.

“You can’t stop the boy going to the Gardens. He’ll want to know why. He’ll be resentful. Let him go. Let him play with the kite there. It’ll be all right.”

“I’m terrified that he will try to take Kendal away from me.”

“He wouldn’t do that. How could he? It would be kidnapping.”

“He is a law unto himself.”

“He wouldn’t do that. Where would he take the child? To Centeville?

"No, of course not. He just wants to see him now and then. “

“Nicole … have you seen him?”

“Yes,” she answered.

“You didn’t tell me.”

“It was only briefly and I thought it would upset you. As a matter of fact, he is concerned about the situation. Everybody is.”

“What situation?”

“We’re on the brink of war. The Emperor is becoming very unpopular.

After what happened to our country at the end of last century we are a sensitive people. “

She managed to subdue my fear for Kendal, but I found it very hard to work while he was out of the house, I arranged that he should go out in the afternoons when I could go with him. In the mornings he should be at his lessons. He was after all nearly five years old.

I knew that he had not seen the Baron for a week. Strangely enough he did not mention him. I had come to realize that children took almost everything for granted. The gentleman was there, he liked to talk to him, he had presented him with a kite . and then he was not there.

That was life, to Kendal.

I was immensely relieved.

But when we had visitors there was continual talk of what they called the uneasy situation.

“How long is the Second Empire going to last?” one of my visitors asked me.

I wondered why he was so intense. I, of course, had not had grandparents who had lived through the Revolution.

“There are people,” I was told, ‘who have felt they were sitting on the edge of a volcano ever since. “

“The Emperor has no right to meddle in Danish and Austro-Prussian wars,” said one.

“The French army is strong and the Emperor himself will lead it.”

“Don’t you believe it,” said another.

“I don’t trust these Prussians.”

I was too concerned with my own affairs to pay much attention, June had been a hot month. It was now over and we were now in what was to prove for France the fatal July of 1870.

Nicole came in one day and breathlessly told me that war between France and Prussia had been declared.

I received a letter that day which completely put thi thought of war out of my mind. It was from Clare and thi news it contained shattered me.

My dear Kate [she wrote], I don’t know how to begin to tell you. This has been a dreadful shock.

Your father is dead. It was so sudden. Of course he was nearing total blindness. Kate, he pretended to come to terms with it, but he never did. He used to go to the studio where you and he had been so happy together and sit there for hours. It was heartbreaking.

He was sleeping badly and I got the doctor to prescribe something for him to take at nights. I thought that was helping him. And then one morning when I went in to waken him . I found him dead.

He looked so peaceful lying there. He looked young. As though he were very happy.

There was an inquest. They were very sympathetic. The coroner said what a tragedy it was that a great artist should be robbed of that which was most necessary to him. Others can lose their sight and accept their fate more easily. But not a man to whom his work had meant so much.

They called it suicide while the balance of his mind was disturbed.

But his mind was as clear as ever. He just felt that he could not go on without his eyes.

I don’t know what I am going to do, Kate. I’m in a state of indecision at the moment. I shouldn’t come here if I were you. It would only make you miserable. Everyone is very kind to me. Frances Meadows made me stay at the vicarage, which is where I am now, and Hope has asked me to go and stay with them, which I shall do at the end of this week. By the time you get this letter I shall probably be there.

There is nothing you can do. Perhaps I will come over and see you later on and we can talk about everything.

Your father spoke of you constantly. Only the day before he died he said how happy he was that you were so successful. He talked of the boy too. It was almost as though he felt he could die happily knowing that you would carry on the tradition.

Dear Kate, I know this is the most terrible shock for you. I shall try to make a new life for myself. I feel so desolate and unhappy, but I thank God for my good friends. I don’t know what I shall do. Sell the house, I think, if you are agreeable to that.

He left me the house and what little he had except the miniatures, of course. They are for you. Perhaps I’ll bring them over to Paris sometime . I’m afraid I’ve told you rather clumsily. I’ve written this letter three times. But there is no way of softening the blow, is there?

My love to you, Kate. We must meet soon. There is a good deal to decide. Clare

The letter dropped from my hands.

Nicole came in. She said: “The Emperor is going to lead the forces.

He’ll cross the Rhine and force the German States to become neutral.

"Why . what’s the matter? “

I said: “My father is dead. He has killed himself.”

She stared at me and I thrust the letter into her hands.

“Oh my God,” she whispered.

She had a wonderfully sympathetic nature and it always amazed me to see her change from the bright sophisticated worldly woman into the warmhearted and understanding friend.

First of all she made a cup of strong coffee which she insisted that I drink. She talked to me, of my father, of his talent, J of his life’s work . and the sudden cessation of that work. I “It was too much for him to endure,” she said.

“He was ? robbed of his greatest treasure … his eyes. He could never’s have been happy without them. Perhaps he is happy now.” | I felt better talking to Nicole and once again I was grateful for her presence in my life.

I suppose it was really because of what had happened that I could only feel a lukewarm interest in the war about which everyone around me was getting so excited.

When the news came that the French had driven the German detachment out ofSaarbriicken, the Parisians went wild with joy. There was dancing in the streets and the people were singing patriotic songs, shouting Vive la France’ and “A Berlin’. Even the little modistes’ girls with their boxes hanging on their arms were talking excitedly about giving the Prussians a lesson they would never forget.

As for myself I could think of nothing but my father. When I had seen him he had seemed happy-content with his marriage to Clare, happy because I was successful and he thought Kendal vas going to paint too. And all the time he had been keeping his thoughts to himself.

If only he had shared them!

There were times when I was on the point of making arrangements to return to England.

What was the use? said Nicole. What could I do? He was dead and buried. There was nothing I could do. Besides, how could I leave the boy?

How could I indeed. I thought of the Baron, prowling round. What would happen if I were not here?

“Moreover,” went on Nicole, ‘it is not easy to travel in wartime. Stay where you are. Wait awhile. You will get over the shock of it. Let Clare come here. You can talk together and comfort each other. “

It seemed sound advice.

Then things began to change. The spirit of optimism had given way to one of apprehension. The war was not going as well as it had seemed to at first. Saarbriicken was nothing more than a skirmish at which the French had had their only success.

Gloom began to show itself in the streets of Paris. A mercurial people once applauding victory with enthusiasm were now sunk in gloom and asking each other, What next?

The Emperor was with the army; the Empress had taken up residence in Paris as Regent; and that first belief that it would soon be over and the Prussians taught a lesson began to fade. The French army was not what it had been thought to be. On the other hand the Prussians were disciplined, well ordered and determined on victory.

Everyone was talking about the war. It was a momentary setback, said some. It was not possible that a great country like France could be humiliated by little Prussia.

Even when sittings began to be cancelled and some of my clients were leaving Paris for the country, I went on thinking of my father and imagining what his thoughts must have been when he made his final and fateful decision. It was not until I heard that the Prussians were closing in on Metz and that the Emperor’s army was in disorderly retreat blocking the roads and stopping the movement of supplies to the front, that I began to see that we were facing real disaster.

Then came the news of the dire calamity at Sedan and that the Emperor, with eighty thousand French troops, was a prisoner of war in the hands of the Prussians.

“What now?” asked Nicole.

“What can we do but wait and see?” I asked.

There was fury in the streets. Those who had been proclaiming the Emperor and crying A Berlin were now fuming against him.

The Empress had fled to England.

September had come. Who would have believed that there could be such changes in so short a time.

Those few days seemed endless.

“They’ll make peace,” said Nicole.

“We shall have to agree to conditions. Then everything will settle down to normal.”

Two days after the fall of Sedan the Baron came to see us.

I was coming down to the salon when I heard voices. A visitor, I thought.

I opened the door and gasped with astonishment, for the Baron came swiftly towards me and taking my hand kissed it. I withdrew it quickly and looked reproachfully at Nicole. I had the impression that she had invited him here.

But this was not so and he dispelled that suspicion immediately.

“I came to warn you,” he said.

“You know what is happening.” He did not wait for a comment from us.

“It’s … debacle,” he went on.

“We have allowed a fool to govern France.”

“He did some good,” Nicole defended the Emperor.

“He is just not a soldier.”

“If he is not a soldier he should not go to war. He misled the country into thinking it had an army which could fight. It was unprepared .. untrained … There was not a chance against the Germans. However, we waste time and God knows we have little of it to spare.”

“The Baron is suggesting that we leave Paris,” said Nicole.

“Leave Paris? To go where?”

“He is offering us the shelter of his chateau until we can make our plans.”

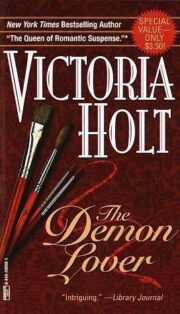

"The Demon Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Demon Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Demon Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.