I spent a great deal of time with the Baron. When I came into the room where he lay I noticed the pleasure which showed in his eyes.

Sometimes he said: “You’ve been a long time.”

Then I would reply: “You don’t need constant care now. You’re getting better. I have other things to do, you know.”

I spoke to him like that, with a touch of asperity just as I used to.

I don’t think he wanted it to change and nor did I. “Sit down there,” he would say.

“Talk to me. Tell me what the madmen are doing now.”

Then I would tell him what I had learned of the war, that the Prussians were surrounding Paris and even penetrating the north of the country.

“They’ll take the towns,” he said.

“They won’t bother about places like Centeville.”

Then I told him goods had almost disappeared from the shops and it was going to be difficult to feed ourselves if it went on like this.

“And you have saddled yourself with another mouth to feed.”

“I owe you that,” I said, ‘and I like to pay my debts. “

“So the balance has changed. You are on the debit side now.”

“No,” I replied.

“But you saved my son’s life and for that I will look after you until you are well enough to stand on your own feet.”

He tried to take my hand but I withdrew it.

“And that other little misdemeanour?” he asked.

“That act of savagery? No, that is still outstanding.”

“I will try to earn a remission of my sins,” he said humbly. That was how our conversation was-much as it had always been, although now and then a light and bantering note would break in.

He was getting better. The leg was healing and he could spend longer walking about the house without exhausting himself. But in the afternoons I used to insist on his resting while I took Kendal out for a walk, leaving Jeanne in charge. He was always watching the door for my return.

“I wish you wouldn’t take those afternoon rambles,” he said.

“We have to go out sometimes. I never go far from the house.”

“I am in a state of anxiety until you return and that is not good for me. Every nurse worthy of the name knows that patients should not be subjected to anxiety. It impedes recovery.”

“I’m sorry you don’t think I’m worthy to be a nurse.”

“Kate,” he said, ‘come and sit down. I think you are worthy to be anything you want to be. I’m going to tell you something extraordinary. Do you know . here I am incapacitated, probably about to be crippled for life, in a besieged city, lying in a room with death looking in at the window, now knowing from one moment to the next what dire tragedy will descend on me . and I’m happy. I think I am happier than I have ever been in my life. “

“Then yours must have been a very wretched existence.”

“Not wretched … worthless. That’s it.”

“And you think this is worthwhile … lying here … recuperating . doing nothing but eating when we can get something to eat… and talking to me.”

“That’s just the point. It’s talking to you … having you near .. watching over me like a guardian angel … not allowing me to stay up too long … bringing my gruel … this is the strangest thing that has ever happened to me.”

“Such situations have not been frequent in my life either.”

“Kate, it means something.”

“Oh?”

“That I’m happy… happier than I’ve ever been… being here with you.”

“If you were well enough,” I reminded him, ‘you would get yourself a horse and be out of the city in an hour. “

“It would take a little longer than that. And there won’t be any horses left soon. They’ll be eating them.”

I shivered.

“They have to eat something,” he went on.

“But what were we saying?

I’d be out of this city with you and the boy. and we should take Jeanne, of course. But these days . there has been something very precious about them for me. “

“Well, you have realized that you’ll be able to walk again one day.”

“Dragging one foot behind me, perhaps.”

“Better that than not walking at all.”

“I know all this and yet it’s the happiest time of my life. How can you explain that?”

“I don’t think it needs an explanation because it’s not true. The happiest times of your life were when you were triumphing over your enemies.”

“My enemy now is the pain in this accursed leg.”

“And you are triumphing over that,” I said.

“Then why am I so contented with life?”

“Because you believe you are the great man and that no harm can possibly come to you. The gods of your Norse ancestors are seeing to that. If anyone attempted to harm you, old Thor would flash his thunder at them or throw his hammer and if that couldn’t save you Odin, the All-Father, would say, ” Here comes one of our chosen heroes.

Let’s warm up Valhalla for him. “

“Do you know, Kate, you are so often right that I cease to marvel every time you display your understanding.”

“Good. Shall I dress your leg?”

“No, not yet. Sit down and talk.”

I sat down and looked at him.

“How strange,” he said, ‘when you think of our being together in that tower bedroom. Oh, what a time that was. What an exhilarating adventure. “

“It was something less than that for me.”

“I have never forgotten it.”

“Nor,” I said pointedly, ‘have I. “

“Kate.”

“Yes?”

“When I was lying here in the beginning, I watched you. I pretended to be unaware …”

“I would expect such subterfuge from you.”

“You seemed to watch over me … tenderly.”

“You were hurt.”

“Yes, but I thought I detected a special caring… a special involvement. Did I?”

“I remembered that you saved my son’s life.”

“Our son, Kate.”

I was silent for a while and he went on: “I’m in love with you.”

“You … in love! That’s not possible-unless it is with yourself, of course, but that is a love-affair of such long standing that it calls for no special mention. In fact it is superfluous to comment on it.”

“I love to be with you, Kate. I love the way you slap me down all the time. I enjoy it. It stimulates me. You are different from anyone I have ever known. Kate, the great artist who is so eager that I should know she pretends to despise me. Pretends… that is the whole point. In your heart, you know you like me … quite a lot.”

“I am grateful that you saved Kendal, as I have told you many times. I appreciate the fact that you came to take him out of the city.”

“To take you too. I shouldn’t have gone without you. I could have got clear of the city … if I had not waited for you.”

“You came for the boy.”

“I came for you both. You don’t think I would have taken him and left you. I just want you to know that I could not have done that.”

I was silent.

“You worry a great deal about that boy, don’t you?”

I nodded.

“He’s a natural survivor. He’s my son. He’ll come through … as we all shall.”

“I fear that something will happen to me. Yes, I fear that terribly.

What would become of him then? It is my main worry. What is happening to the children of those who have been killed . or die of starvation? ”

“There is no need to worry about Kendal. I have made arrangements.”

“What arrangements?”

“I have made provision for him.”

“When did you do that?”

“When I saw him, when I assured myself that he was my son, I arranged that he should be well provided for whatever happened.”

“What of this country? What will happen to it? What happens when countries are overrun by their enemies? Will what you hzve done be worth anything if France is a beaten nation?”

“I have made arrangements both in Paris and in London. After all, he is half English.”

“You have really done this!”

“You look at me as though you regard me as some sort of magician. I may be in your eyes, Kate, but these arrangements are commonplace.

They can be made by any man of business. I have seen the way things were going here. I had made plans to leave for a while, but I wanted to take you and the boy with me. However, that failed. But at least. if the boy were left without either of us, there would be people in London who would find him and he would be looked after. “

I could not speak. Even lying there he exuded power. I had the feeling that while he was there all would be well with us.

“You are pleased with me,” he said.

“It was good of you … kind of you.”

“Oh, come, Kate, my own son! I always wanted a boy like that. He satisfies me… completely, as you do.”

“I am glad you have some regard for him.”

“One day he may be a great artist. He will get that from you. From me he will get his handsome looks …” He paused waiting for comment, but I gave none. I was too moved to speak.

“His handsome looks,” he went on, ‘and his determination to get what he needs . his force, his strength of purpose. “

“None of which qualities could come from anywhere else,” I said with a mockery tinged with gentleness. He had lifted a great burden from my shoulders.

He said: “Had you been here when I came I would have got you out of Paris. I had planned to take us all… you, the boy’ Nicole . and of course the governess. Poor Nicole …”

I said: “You loved her.”

“She was a good woman … a good friend to me. We understood each other. It is hard to believe that she is dead.”

“You have known her a long time.”

“Since she was eighteen. My father did not want me to marry young. He chose a mistress for me. He wanted to make sure that I made the right marriage. He put great store in the calibre of the offspring.”

“Like breeding horses?”

“You could say that. All the same, the principle applies.”

“Nicole, I presume, had not the necessary points?”

“Nicole was a beautiful and clever woman. She had been married to a bank clerk. My parents arranged the meeting with her mother. We liked each other and it turned out to be a very satisfactory relationship.”

“Satisfactory for you and your calculating family, perhaps. What of ” She never gave any sign that she was not satisfied with the arrangement. It is the way things are managed in France in families like ours. The necessity of a mistress was understood and one was provided. It was marriage which was the serious question. “

“So that is how to make a perfect marriage. It didn’t work in your case, did it?”

“It’s something you learn as you get older. You can make plans but you forget that when you are dealing with people you can go wrong.”

“So you have learned that at last.”

“Yes, at last I have learned it.”

“You thought the blood of princes would enhance the family strain.” I laughed.

“It’s a matter of opinion, of course. And you are clearly not satisfied with your marriage … royal blood though there is.”

“I am completely dissatisfied with my marriage. I think often of how I can end it. Lying here, I have been thinking a great deal about that.

If ever I get out of this place, I shall do something. I shall not spend the rest of my life shackled.

"Don’t you agree that I should be a fool to let things stay as they are? ”

“I can’t see how you can do anything else. You planned and your plans went wrong. You thought your Princesse was a puppet to be picked up and put in a certain place at your will. Her duty was to supply a little blue blood to the great Centeville stream .. though I should have thought—in your opinion at least-no royal blood could compare in worth with that of barbarian Norsemen. However, you picked her and put her where you wanted her-and lo, you have discovered that she is not a puppet. She is a warm, living human being who, having no wish to make the donation of royal blood her mission in life, turned to someone else who pleased her better than the barbarian Baron. There is only one thing to be done now. As we say in England: You have made your bed. Now you must lie on it.”

“That is not my way. You should know that well enough by now.”

“If things don’t please you the way they are, you set about changing them. That is it, is it?”

“Yes, Kate.”

“Well then, what will you do? There would have to be a dispensation, wouldn’t there, to annul the marriage?”

“On the grounds other adultery it should be easy.”

I burst out laughing.

“I am glad I amuse you,” he said.

“Oh, you do. Her adultery. You must admit that is very funny. Besides, is it adultery? She had her lover before her marriage. She did though in a more human, civilized manner what you have done many times, I am sure. And you talk about divorcing her for adultery. You see why you make me laugh.”

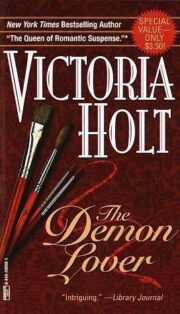

"The Demon Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Demon Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Demon Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.