“No,” I said,”I can’t.”

“That’s the answer to the first question. We are two strong people, Kate. We are not going to let anything stand in our way, are we?”

“Some things must.”

“But you love me and I love you. It is no ordinary love, is it? It’s strong. We know so much about each other. We’ve lived each other’s lives. Those weeks in Paris … they bound us together. I wanted you from the moment I saw you. I liked everything about you, Kate … the way you looked, the way you worked … the way you tried to deceive me about your father’s blindness. I wanted you then. I was determined to have you. That business of Mortemer was an excuse.”

“You could have suggested marriage then when you were free to do so.”

“Would you have had me?”

“Not then.”

“But now you would. Oh yes, you would now. Don’t you see, we had to be ready. We had to know. We had to go through all we went through to learn that this thing we have for each other is not passing … not ephemeral … as so many loves are. This is different. This is for a lifetime … and it is worth everything we have.”

“You’re so vehement.”

“I have said that about you. It is what we like about each other. I know what I want and I know how to get it.”

“Not always.”

“Yes,” he said firmly.

“Always. Kate, you must not go yet. If you do, I shall come after you.”

I said nothing. We sat there side by side and I lay against him while he held me tightly.

I felt comforted by his presence. For the first time I was facing the truth. Of course I loved him. When I had hated him, my feeling for him had overwhelmed everything else. From hatred I had slipped into love and as my hatred had been strong and fierce, so was my love.

But I was going to England. I knew I had to go. Clare had made me see that.

I roused myself.

“I must get back. Clare will be coming from the castle. They will be expecting me and wondering where I am.”

“Promise me one thing.”

“What is that?”

“That you will not attempt to leave without first telling me.”

“I promise that,” I said. ” ” Then we stood for a while and he kissed me in a different way from that in which he had previously, gently, tenderly.

I was so filled with emotion that I could not speak.

Then he helped me to mount Fidele and we rode back to the castle.

“Kendal,” I said, ‘we are going to England. “

He stared at me and I saw his mouth harden. He looked remarkably like his father in that moment.

I went on: “I know you hate leaving the castle, but we have to go. You see, this is not our home.”

“It is our home,” he said angrily.

“No.. no… We are here because there was nowhere else for us to go after we left Paris. But you can’t stay in other people’s houses for ever.”

“It’s my father’s house. He wants us here.”

“Kendal,” I said, ‘you are not grown up yet. You must listen to what I say and know that it is for the best. for you and for all of us. “

“It’s not the best. It’s not.”

He was looking at me as he never had before in the whole of his life.

There had always been a strong bond of affection between us and I could not bear to see that look in his eyes. It was almost as though he hated me.

Could Rollo mean so much to him? He really did love the castle, I knew. True, it was a storehouse of wonderment to an imaginative child; but it was more than that. He had made up his mind that he belonged here and Rollo had done his best to make him feel that.

He robbed me of my virtue, I thought. He turned my life upside down; and now he would rob me of my child.

I felt angry suddenly. I said: “I see it is no use talking to you.”

“No, it isn’t,” said Kendal.

“I don’t want to go to England. I want to stay at home.” Then I saw that stubborn look in his face again, which reminded me so much of his father. I thought: He is going to be just like him when he grows up, and my fear for him was mingled with my pride.

I said: “We will talk of it later.”

I did not feel I could bear to say any more.

It was late that afternoon. Jeanne was cooking which she liked to do -and Clare had just come in. She had been to the castle.

“Madame la Baronne is in a defiant mood today,” she said.

“I don’t like the way things are going up there.” She looked at me anxiously.

“This time next week we shall be setting out for home,” I reminded her.

“It’s best,” she said compassionately. I thought it was wonderful, the way she understood.

“Where is Kendal?” she went on.

“He went off with William playing that hunting game they are so fond of, I believe. I saw them go off. He was carrying something. It looked like a bag of some sort.”

“Laying his clues, I suppose. I am so pleased that he and William have become friends. It is such a good thing for that poor little boy. I’m afraid he didn’t have much of a life before.”

“No. I wonder what he will do when we have gone.”

Clare knitted her brows.

“Poor little thing! He will revert to what he was before.”

“He has changed a good deal since we came.”

“I can’t bear to think of him. Has Kendal told him we are going?”

“No. Kendal won’t accept that we are. He became so angry … so unlike himself… when I talked of it.”

“He’ll be all right. Children adjust very quickly.”

“He seems to have become obsessed by the place … and the Baron.”

“A pity. It’ll all come right in the end.”

“You believe in happy endings, Clare.”

“I believe that we can do a great deal towards bringing them about,” she said quietly.

“I’ve always thought that.”

“You’re a great comfort.”

“Sometimes I think I ought not to have come here.”

“Why ever should you think that?”

“When I came, I offered you a way out. Sometimes I think that is the last thing you wanted.”

I was silent, thinking: I believe she notices everything.

“I needed a way out, Clare,” I said.

“You showed me a way.

So please don’t say it would have been better if you hadn’t come. “

We were both silent for some time. I was thinking about Clare and what her life must have been like when she was looking after her mother until she died . and then coming to look after my father. Now it seemed she was looking after me. It was true that she was the sort of person who spent her life looking after other people and had no real life other own. It must have been about half an hour later when she reminded me that Kendal had not come home.

“He is late,” I agreed.

Jeanne came in then and asked where Kendal was. We all agreed that he was late, but we were not really concerned until about an hour later when he was still not home.

“Wherever can he have got to?” asked Jeanne.

“He should have been back long ago.”

“He must have got caught up in the game.”

“I wonder if he is at the castle,” suggested Jeanne.

Clare said she would go and look, and put on her cloak and went out.

I was beginning to feel uneasy. Clare came back soon looking very disturbed. Kendal was not at the castle. William was not there either.

“They must still be playing,” said Jeanne. But two hours later when they had still not returned I was seriously alarmed. I went up to the castle. I was met by one of the maids who looked at me with that speculation to which I was becoming accustomed.

I cried out: “Has William come home yet?”

“I don’t know, Madame. I will go and enquire.”

It soon transpired that William was not at home. Now I knew something was wrong.

Rollo came into the hall.

“Kate!” he cried, the delight obvious in his voice at the sight of me.

I cried out: “It’s Kendal. He’s out somewhere. We expected him back hours ago. William is with him. They went out this afternoon to play in the woods as they often do.”

“Not back yet! Why, it will be dark soon.”

“We must find him,” I said.

“I’ll make up several search parties. You and I will go together, Kate. Let’s go to the stables. I’ll bring a lantern and alert the others. There’s no moon tonight.”

In a short time he had formed search parties and sent them off in different directions. He and I rode off together.

“To the woods,” he said.

“I’m always afraid of the Peak. If they got too near the edge … there might be an accident.”

We rode in silence. I was getting really frightened now. It was dark in the woods and all sorts of fearful pictures kept flashing into my mind. What could have happened to them? Some accident? Robbers? What would they have that was worth stealing? Gypsies! I had heard of them carrying off children.

I felt sick with anxiety and at the same time relieved because Rollo was with me.

We went to that spot which Marie-Claude had first shown me and where I had met Rollo later. I peered into the eerie darkness. We rode right to the drop. Rollo dismounted and gave me his horse to hold while he went to the edge of the ravine and looked over.

“Nothing down there. The ground hasn’t been disturbed. I don’t think they came to this spot.”

“I have a feeling they are in the woods,” I said.

“They came to the woods to play their game. They couldn’t have played it in the open country.”

Rollo shouted: “Kendal, where are you?”

His own voice echoed back.

Then he did a shrill whistle. It was earsplitting.

“I taught him how to do that,” he said.

“We practised it together.”

“Kendal, Kendal!” he called.

“Where are you?” And then he whistled again.

There was no response.

We rode on and came to a disused quarry.

“We’ll ride down here,” said Rollo, ‘and I’ll shout again. It’s amazing how one’s voice echoes from here. I used to call to my playmates when I was a boy. You get the echo back. I showed this to Kendal too. “

I wondered briefly how often they had been together. When Kendal went off into the woods, was the Baron there too? Did he join in the game of hunter and hunted?

We rode up to the top of the quarry and shouted again.

There was silence for a few seconds and then . unmistakably . the sound of a whistle.

“Listen,” said Rollo.

He whistled again and the whistle was returned.

“Thank God,” he said.

“We’ve found them.”

“Where?”

“We’ll find out.” He whistled again and again it came back.

“This way,” he said.

I followed him and we made our way through the trees.

The whistle was close now.

“Kendal,” called Rollo.

“Baron!” came the answer; and I don’t think I ever felt so happy in my life as I did at that moment.

We found them in a hollow-William white and scared, Kendal defiant.

They had contrived to build a tent of some sort with a sheet spread out over the bracken.

“What’s this!” cried Rollo.

“You’ve led us a pretty dance.”

“We’re camping,” said Kendal.

“You might have mentioned the fact. Your mother has been frantically wondering where you were. She thought you were lost.”

“I don’t get lost,” said Kendal, not looking at me.

Rollo had dismounted and pulled back the sheet.

“What’s this? A feast or something?”

“We took it from the kitchens in the castle. There was a lot of food there.”

“I see,” said Rollo.

“Well, now you’d better come back quickly because there are a lot of people searching the countryside for you.”

“Are you angry?” asked Kendal.

“Very,” said the Baron. He seized Kendal and put him on his horse.

“Am I going to ride back with you?” asked Kendal.

“You don’t deserve to. I ought to make you walk.”

“I’m not going to leave the castle,” announced Kendal.

“What?” cried Rollo.

“I’m going to stay with you. This is my home and you are my father.

You said you were. “

Rollo had turned to me and I was aware of his triumph. The boy was his. I knew that he was very happy in that moment.

William was standing up looking expectantly about him. Rollo lifted him up and set him on my horse in front of me.

“Now we’ll get these scamps home,” said Rollo.

As we approached the castle several of the servants saw us approaching and a shout of joy went up because the boys were safe.

I dismounted and helped William down.

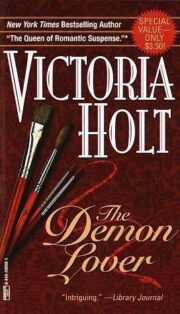

"The Demon Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Demon Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Demon Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.