The Baron snapped his fingers.

“Bertrand has not the feeling for the castle … wouldn’t you say so, Nicole?”

“Well, it is yours, isn’t it? He, like the rest of us, is but a guest here.”

The Baron patted Nicole’s knee rather affectionately. I thought he must be on very familiar terms with her.

“Well, Mademoiselle Collison,” he said, ‘you know how it is. This is my home. It is built by my ancestor and is one of the first the Normans built in France. There were Centevilles living here from the early days when Great Rollo came harrying the coast of France, with such success that the French King said that the only way to stop this perpetual harassment is to give these invaders a corner of France, which he did. And there was Normandy. Never make the mistake of thinking we are French. We are not. We are the Norsemen come to France from the magnificent fjords. “

“The French were a very cultivated people when the savage Norsemen came in their long ships looking for conquest,” I reminded him.

“But the Normans were fighters, Mademoiselle Collison. They were the unvanquished. And Centeville Castle was here at the time our great William the Duke conquered you English and forced you to submit to Norman rule.”

“The Normans won on that occasion,” I said, ‘because King Harold had just come down to the south after winning a victory in the north. If he had been fresh for the fight, the victory might have gone the other way. Moreover, you say you defeated the English. The English of today are a mixed race. Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Romans . and yes, even glorious Normans. So it seems to me a little misplaced to crow over the victory of William all those years ago. “

“You see how Mademoiselle Collison corrects me, Nicole.”

“I am delighted that she puts forward such a good case against you, Rollo.”

Rollo! I thought. So that is his name. I must have shown my surprise for he went on: “Yes, I am Rollo. Named after the first Norman to turn this corner of France into Normandy. His battle cry was ” Ha! Rollo! ”

And it continued to be the Norman battle cry for centuries. “

“It is no longer in use, I trust.”

I could not understand this impulse in me to attack him at every turn.

It was most unwise since we had to try to please him; and here I was antagonizing him before we began.

But he did not look displeased. He was actually smiling, and it occurred to me that he was enjoying the conversation. I was being as unpleasant as I could without being rude. How strange that he-who was used to sycophants-should not object. It must be because it was so rarely that anyone stood out against him.

But Nicole was by no means a sycophant. Perhaps that was why he liked her as he obviously did.

Bertrand had returned.

He said to me: “Perhaps you would like to take a walk in the grounds before retiring for the night?”

I rose with alacrity.

“That would be delightful,” I said.

“You need a wrap. Shall I go and get one?”

“Take mine,” said Nicole.

“It will save a journey up to your room. I don’t need it.”

She handed me a scrap of chiffon which seemed to take its colour from whatever it covered. It was decorated with a border of sequinned stars.

“Oh.. thank you,” I said. “It looks too… pretty. I should be afraid to harm it.”

“Nonsense,” said Nicole coming to me, and herself put it round my shoulders. I thought she was very charming.

Bertrand and I went out through the courtyard to the moat.

“Well, what did you think of the Baron?” he asked.

“It’s rather too big a question to answer briefly,” I said.

“It’s like confronting someone with the Niagara Fails and asking for an immediate opinion.”

“He would be amused to hear himself compared with them.”

“I would say he is very conscious of his power and wants everyone else to be too.”

“Yes,” agreed Bertrand.

“He likes us to recognize that and to do exactly as he wants us to.”

“Which is all right as long as it coincides with what one wants oneself.”

“You are perceptive, Mademoiselle. That is exactly how it has been for me so far.”

“Then,” I said, ‘you must be prepared for the day when it is not. I thought Madame St. Giles charming. “

“She is considered to be one of the most attractive women in society.

Her association with Rollo has lasted for several years. “

“Her… association!”

“Oh! Did you not guess? She is his mistress.”

“But,” I began faintly, “I thought he was going to be married to this Princesse.”

“He is. I suppose it will have to end with Nicole then … or perhaps there will be just a lull. She’s prepared for that. She’s a woman of the world.”

I was silent.

He laid his hand on my arm.

“I’m afraid you are rather shocked. Did you not know that there was this relationship?”

“I’m afraid I’m rather unworldly. Nicole … she doesn’t seem to be upset.”

“Oh no. She always understood that there would come a time when he would marry. He has several mistresses, but Nicole was always the chief.”

I shivered beneath Nicole’s wrap. His hands would have been on that chiffon, I thought. I pictured him with Nicole . sensuous . cynical . It was a horrible picture. I did not want to paint that miniature. I realized that one could learn too much about a subject.

The next morning our ordeal began. I arranged a chair for the Baron where the strong light fell on his face. My father sat opposite him.

We had decided that the support should be ivory which had proved to be ideal since the beginning of the eighteenth century. I sat in a corner watching. I was memorizing every line of his face: the sensuous lips which could be cruel, the rather magnificent high brow and the strong blonde hair springing from his head.

He had told us that the completed miniature would be set in gold and the frame should be studded with diamonds and sapphires. For that reason he wore a blue coat and it certainly accentuated his colouring; it even put a hint of blue into the grey eyes.

My fingers itched to hold the brush. I was deeply aware of my father. He worked quietly and without apparent tension. I wondered whether he was aware of how much he could not see.

This morning would tell us a great deal whether it was possible to carry out this plan or not. I was not sure what sort of miniature I could do from memory or from my father’s work. I was sure I could have made a superb portrait if I could have gone about it in the normal way. I would bring out his arrogance. I would capture that look which suggested that the whole world was his. I would paint in a little of the animosity I felt towards him. I would make a portrait which was absolutely him . and he might not like it.

He talked while my father worked and mainly to me.

Had I been to the Bavarian Court with my father? I told him I had not.

He raised his eyebrows as though asking:

Why not, since you came to Normandy?

“Then you did not see the picture of the Grafin and her inner beauty?”

“I very much regret not having seen it.”

“I feel I have met you before. It must be in the miniature of the Unknown Woman. I suddenly feel she is unknown no longer.”

“I look forward to seeing it.”

“And I to showing it to you. How is it going, Monsieur Collison? Am I a good sitter? I look forward to seeing the work as it progresses.”

“It is going well,” said my father.

“And,” I added, ‘we make a rule that no one sees a miniature before it is finished. “

“I don’t know if I shall agree to that rule.”

“I am afraid it is necessary. You must give a painter a free hand to do what he wishes. To have your criticism now would be disastrous.”

“What if it were praise?”

“That, too, would be unwise.”

“Do you always allow your daughter to lay down the rules, Monsieur Collison?”

“It is my rule,” said my father.

He told me then about certain paintings he possessed not all miniatures by any means.

“How I shall enjoy gloating over my treasures to you, Mademoiselle Collison,” he added.

After an hour my father laid down his brush. He had done enough for the morning, he said. Moreover, he guessed the Baron must be tired of sitting.

The Baron rose and stretched himself, confessing that it was unusual for him to sit so long at one time.

“How many sittings shall you need?” he asked.

“I cannot say as yet,” replied my father.

“Well, I must insist that Mademoiselle Collison remains with us so that she may divert me,” he said.

“Very well,” I replied, perhaps too eagerly.

“I shall be there.”

He bowed and left us.

I looked at my father. I thought he seemed very tired. He said: “The light is so strong.”

“It is what we must have.”

I studied the work he had done. It was not bad but I could detect an unsure stroke here and there.

I said: “I have been studying him closely. I know his face well. I am sure I can work from what you have done and what I know of him. I think I had better start immediately and perhaps work always as soon as he has gone so that I have the details clearly in my mind. We’ll have to see how it goes. It will not be easy to work without a living model.”

I started my picture. I could see his face clearly and it was almost as though he were sitting there. I was revelling in my work. I must get that faint hint of blue reflected from the coat into those cold steely eyes. I could see those eyes . alight with feeling. love of power, of course. lust. yes, there was sensuality about the mouth in abundance. Buccaneer, I thought.

Norseman pirate. It was there in his face.

“Ha! Rollo!” sailing up the Seine, pillaging, burning, taking the women . oh yes, certainly taking the women . and taking the land . building strong castles and holding them against all who came against him.

I don’t think I ever enjoyed painting anyone as much as I enjoyed painting him. It was because of the unusual method, I suspected; and because I had a strong feeling of dislike for him. It was a great help to feel strongly about the subject. It seemed to breathe life into the paint.

My father watched me while I worked.

I laid down my brush at length.

“Oh, Father,” I said.

“I do want this to be a great success. I want to delude him. I want him to have the Collison of all Collisons.”

“If only we can work this together …” said my father, his face breaking up in a helpless sort of way which made me want to rock him in my arms.

What a tragedy! To be a great artist and unable to paint!

It was a good morning’s work and I was very pleased with it.

After dejeuner which my father and I took alone as Bertrand had been summoned to go off somewhere with the Baron and Nicole, I suggested that my father take a rest. He looked tired and I knew that the morning’s work had been more than a strain on his eyes.

I conducted him to his room, settled him on his bed and then, taking a sketch-pad with me as I often did, I went out.

I went down to the moat and sat there. I thought of how Bertrand and I had come here and how we had talked and what a pleasant day it had been. I hoped we should see more of each other. He was so different from the Baron - so kind and gentle. I could not understand why women like Nicole could demean themselves as she had done for the sake of men like the Baron. I found him far from attractive. Of course he had great power and power was said to be irresistible to some women.

Personally I hated all that arrogance. The more I saw of the Baron the better I liked Bertrand. It seemed to me that he had all the graces.

He was elegant, charming and above all kindly and thoughtful for others-qualities entirely lacking in the mighty Baron. Bertrand’s task had been to put us at our ease on our arrival and this he had done with such perfection that we had become good friends in a very short time, and instinct told me that our friendship had every chance of deepening.

While I had been thinking I had been idly sketching, and my page was full of pictures of the Baron. It was understandable that he should occupy my thoughts as I had to paint a miniature of him in a manner I reckoned no miniature had ever been painted before.

There he was in the centre of my page-a bloodthirsty Viking in a winged helmet, nostrils flaring, the light of lust in his eyes, his mouth curved in a cruel and triumphant smile. I could almost hear his voice shouting. I wrote below the sketch “Ha! Rollo.”

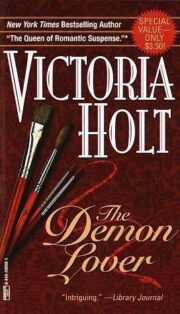

"The Demon Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Demon Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Demon Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.