Adair’s hands closed around the book. “I must have it. What is your price?”

At this, the shopkeeper’s face puckered as though he’d bitten a lemon. “So, this is the tricky part, your lordship, which I beg to explain to you. There is another gentleman who is interested in the book as well. He is a longtime customer of mine. I dare not anger him by refusing him.”

“Then why did you bring me here if you have no intention of selling it to me?” Adair demanded. He felt his blood boil in his brain.

“It’s not that I have no intention to sell it to you. I wish that it were possible. I will speak to the other man, but I cannot see him stepping aside. He is a rabid collector, you understand. It’s just that I . . . I knew you would like the opportunity to see it, as you’ve surely never seen a book of its kind before,” he said, trying to assuage Adair’s anger. “I was acting in what I judged to be your interest, my lord.”

Youthful desire seemed to short-circuit Adair’s ability to reason. “I’ve dealt with crafty merchants before: you are obviously hoping to drive up the price by having us both make you an offer on this book,” Adair said impatiently, his grip tightening around the volume. “Very well, let me cut to the chase: I will pay double whatever your other customer offers. You have but to name your price and I will pay it.” His offer was reckless and he knew it. He had only so much money at his disposal.

The merchant’s face glowed pale in the dimness of the shop. “You’re very generous, my young lord, but I can’t accept your proposition. I beg you, let me speak to my other customer—”

“Consider this a deposit.” Adair dug his money purse from a pocket and slapped it on the table before the shopkeeper, who let his gaze rest on the plump sack for a long, silent moment.

Adair began wrapping the book in its deerskin cover, anxious to escape with his prize while the bookseller was distracted. “And need I remind you in whose house I am a guest? The man who rules the principality, the doge of Venice. Don’t be a fool. It would only take one word from me for you to end up in the dungeons . . .” he said, his bravado betrayed by a slight quaking to his voice.

At those unfortunate words, the bookseller’s servile demeanor changed. He gave a long, irritated sigh and stiffened underneath his leather apron. “Ah, my lord . . . I wish our discourse had not deteriorated so quickly. I’d hoped you would not besiege me thus with idle threats that would only harm us both. Getting the law involved in our private transaction would get both of us in terrible trouble. And which of us is the more serious heretic? I may be a peddler of the occult, but you are the sinner who wishes to give over his soul to the devil, or so the inquisitors will see it. So while I doubt that you would make good on your threat, I prefer not to do business with men who would treat me thus.”

Though he sensed it would do no good, Adair decided to press his bluff. “I will not be made a fool of, or cheated. You summoned me here and dangled your wares before me. I’ve offered you good golden ducats at a more than fair price. If you wish to avoid any unpleasantness, I suggest you act like a merchant and sell the book to the first customer who offers to buy it, and that is I. I consider our business concluded.” He tucked the package under his arm and tried to brush by the shopkeeper, but the man put out his hand, catching Adair in his chest.

“I’m sorry, my lord, but I cannot let you have the book. Take back your coins and leave the—”

Adair’s dagger was drawn before the shopkeeper could finish his sentence. Because Adair was flustered, his hand was unsteady and he was not as precise as he would’ve preferred: he only meant to send the man back a step or two, but ended up driving the tip of the blade into the man’s chest. The leather apron saved the shopkeeper from serious harm, but he staggered to his knees, clutching the wound. In the moment of confusion, Adair darted out of the shop, his treasure hidden under his cloak.

With such a rare and damning book, Adair knew he had to take special precautions to keep it from being discovered. While he appreciated the book’s beautiful construction, its peacock linen cover was something of a drawback as it made the book stand out no matter where you placed it. When he tried to hide it among his other books, the bright cover invariably drew the eye, and then of course the hand was sure to follow. It pained him to tuck it beneath floorboards or behind a loose rock in the wall, but there was no way to leave it out in the open. It was too conspicuous. He was careful to move it between hiding places in his bedchamber: it was the doge’s palazzo after all, with more servants than the population of entire villages, and people were in and out at all hours, tidying up the room when he was not around. He stayed up late at night to read the book in secret by candlelight. Each page revealed whole new areas of alchemical thought and practice for him, for which he was amazed, and grateful. It was as though he was given all the sweet water he could drink after a prolonged and painful drought. Adair took the example of the monk who created this book and copied out his favorite recipes on rough paper in his native language so that he would have a spare copy in case something happened to the original.

He was returning late one night to the palazzo from a lecture at the home of his tutor of medicine, Professore Scolari, when he became aware that he was being followed. He was in a lonely alley at the time with only a quarter moon overhead for light. The alley had been so quiet that he had felt certain there was no one else with him, and sure enough, when he turned to confront his assailant, there was nothing there but blackness.

Then, without warning, a man Adair had never before laid eyes on stepped out of the inky emptiness. Adair could not believe his eyes: it was as though the man had been hiding inside a black cloud that completely obscured his presence. He was older and imposing, tall and broad as a church door. He had piercing gray eyes and a thick mustache, his long black hair streaked with silver. He wore a cloak of burgundy velvet trimmed in ermine, fine enough for a king to wear.

The conjurer pointed a finger at Adair. “Stand right where you are, you devil’s stripling. You will not pass. I believe you have something that belongs to me.”

Adair stepped back, his hand on his sword. “How can that be when I don’t know you, sir?”

The man continued to glare at him. “Don’t feign ignorance; you’re not that good an actor. The book, sir. You took it from a friend of mine. You have frequented a shop near the Plaza Saint Benedict, have you not? You know the shopkeeper, Anselmo?”

“I didn’t take it from your friend, I bought it. He was more than fairly compensated. I would be careful, sir, for I am a ward of the doge—”

“I know all about your place in the doge’s household,” the conjurer said with a sneer. “And we both know he would cast you out and return you to your heathen family’s estate if he found out about your extracurricular interests. And I also know that the doge currently has at least a dozen such young men living under his roof, too many to keep track of. Zeno probably wouldn’t even be able to identify your body—if you were to come to such an unfortunate end.” The stranger was right: he had seen through Adair’s bluff. “Don’t worry, boy—I’m no assassin. I’m only here to take what’s rightfully mine. Do you know what I am?”

There was little question that this old man was a mage, a practitioner of some skill and ability, and angry with Adair for being so presumptuous as to buy (or, rather, steal) the book out from underneath him. He’d come to settle the score. Adair sheathed his sword quickly and made a low bow. “My sincere apologies, sir. I meant you no disrespect. The shopkeeper had summoned me to his store, had he not? I thought the man was merely trying to force an exorbitant sum from me with the pretense of having another buyer. I will return the book to you without argument if you return the sum I paid your friend Anselmo.”

The large man relaxed, shifting his weight to his back leg, his hand dropping from his sword. “I’m glad you’re being so reasonable,” he said with some caution.

“Obviously, I do not presently have the book with me. Let me deliver the book myself to your house tomorrow evening,” Adair said.

The old man narrowed his eyes. “Is this a trick? You want me to tell you where I live so you can send the doge’s men to arrest me? How do I know I can trust you, after what you did to Anselmo?”

Adair bowed low again in a show of deference. “By the fact that you were able to follow me unseen within your ingenious black cloud, I can tell you are a man of considerable expertise in the magical arts, whereas I am a novice and have only begun in my scholarship. You would do me a great honor if you would allow me to set this matter right between us, sir.”

“That black cloud is nothing, a minor trick. You’d do well to remember that imbalance in our powers; I would not hesitate to bring the worst punishment imaginable down upon you should you betray me.” The old man thought, rubbing his grizzled chin. “All right, since you plead so prettily, I’ll let you bring the book to me. But I warn you: I’ll be watching your every move through the soothsayer’s bowl and if you cross me, it will go very badly for you. Do you understand?” He watched Adair nod. “Come to the Plaza Saint Vincent tomorrow at midnight. You’ll know which house is mine.”

Adair bowed a third time, and when he rose, the man and the black cloud had disappeared.

PRESENT DAY

Adair woke with a start and had to shake his head hard to clear visions of the dark Venetian alley from his mind and remember that he was safe in his fortress off the coast of Sardegna. He looked down at Lanore—she was still asleep, oblivious to his alarm—and then blinked and peered around the darkened room, half expecting to see the conjurer step out of the inky blackness.

Adair hadn’t thought of Cosimo Moretti, the old conjurer, for centuries. He’d actively suppressed thoughts of Cosimo (and his demise) for a very long time and could see no reason why he should think of him—even worse, dream of him—now. Adair couldn’t help but think it had something to do with the spell he’d cast over Lanore or the Venetian book with its peacock-blue cover that she had returned to him.

Adair rose from the bed, readjusted his twisted clothing, and went downstairs to his study, tiptoeing through the silent house. He didn’t want to risk waking the girls, so he didn’t turn on a light until he reached his study. The book fairly glowed from across the room, from where it sat on his desk.

He pressed a hand to the cover, quite filthy by now, with centuries of grime effacing the blue linen, and he could practically feel magic emanate from it like a pulse. Cosimo’s magic; he’d felt the same jangly vibrations in Cosimo’s presence, just as he assumed others felt something similar when they were near him. Once a person made contact with the other world, it left its mark on him. It had made Adair into something like a portal, with the hidden, magical world a heartbeat away.

ELEVEN

Once I stepped through the door of the Moroccan hotel, I was back in the fortress, presumably in the hall on the second story. The dusty smell of the hotel in Fez lingered, however, clinging to my sweaty skin and damp cotton dress, proof that it hadn’t been completely fabricated in my mind—unless the subtle mix of ginger, mint, sandalwood, and jasmine were also figments of my imagination.

The hall was still a dim and empty expanse of red carpet and dark wooden doors. No sound echoed down the long corridor, the house as quiet as a mausoleum. In the unbroken stillness, I suddenly noticed that the flames standing atop the candles in the iron wall scones had begun to quiver, tickled by a draft coming from an unknown direction. Someone had opened a door.

I strained so hard listening for a sound that my ears started to ache. Then I heard what I’d been waiting for: a muffled thump, like a ball being dropped onto a carpet. And a second thump. Whatever it was, it sounded very solid, ominously so. The cloven hoof of a demon? I wasn’t going to stay and find out. My hand closed around the nearest brass doorknob. I gave it a turn, held my breath, and slipped inside another room.

I stepped into a forest, just on the other side of the door. The forest was vast—I could tell by the vacuous silence—and a light snow was falling; only a few flakes made it through the canopy of bare branches to the ground. A fuller stand of trees stood ahead of me, mostly pine and all frosted with new snow, and behind it another stand and another. My breath misted on the cold air and my skin tingled—not from the cold but because I was home.

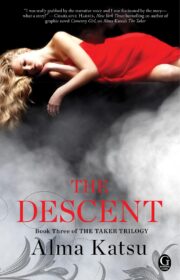

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.