It was Elena. She must’ve guessed what he was up to and followed him. She had put her hand most deliberately on his cock and Adair was so surprised that speech failed him. She used that moment of weakness to kiss him. Even though it was she who threw herself against him, her mouth pressing to his, she still managed to yield softly to him. She was as tender as he imagined she would be, a hot spot of need reaching for him and melting under him simultaneously. Her hands crept to his chest, her palms pressed against the front of his tunic.

Once the kiss was over and she’d settled back to her feet, she looked into his eyes saucily. “May I help you with that, my lord?” she asked. Her hands went to work before he could even reply. Her eyes were locked on his manhood the entire time. While she obviously took pleasure from what she was doing, it was just as obvious that this was not her first time. She brought him to climax expertly, catching his seed in a handkerchief at the end. While he watched in openmouthed surprise, she tucked the handkerchief down the front of her tunic, between her breasts, and then rinsed her hands in a nearby washing bowl.

In the fog of his brain, awash with pleasure and shock, Adair suddenly understood why Elena had been sent to live away from home: the girl was an incorrigible nymphomaniac. She’d probably disgraced herself, though she was probably not so foolish as to give up her hymen to anyone, not before her wedding. She had been packed off to faraway Venice because no one would have heard of her indiscretions, and there was even a possibility that she might snare a suitable husband. Undoubtedly the bishop was trying to reform Elena while she was living under his roof, and having about as much success as the doge was having with Adair. In some respects, she was no different than he.

“Elena, we must talk—but not here,” he said, leading her by the hand out into the hall. Although there was the possibility of being overheard as servants passed by with platters and pitchers to serve the partygoers in the great hall, it was less incriminating than being caught together by the piss pots. And he needed to set her straight and let her know that he had no intention of marrying her, despite her godfather and the doge’s obvious attempt to pair them off.

She looked at him now with a mixture of suspicion and resignation. “Oh—I’ve gone and done it, haven’t I? Been too eager? It’s just that I wanted to see it. Your prick. I knew it would be lovely, and it is. You won’t tell my godfather what I’ve done, will you? He’ll be so disappointed.”

Adair put his hands on her shoulders. “Elena, that was a very generous courtesy you did for me just now, and while I appreciate your attentions, I must tell you—you’re wasting your time with me. I have no intention of marrying. Not you, not anyone.”

She drew back as though Adair had told her he had the plague. “What do you mean? Are you thinking of taking vows?”

“Becoming a priest? Oh no . . . Although, you might think my intention not so dissimilar . . .” He stood as tall as he could, trying to make himself seem older and wiser. “I’m going to become a scholar and devote myself to study of the natural world.”

She sized him up cagily. “Yes, I heard you intend to become a physician.”

“That’s part of it, but I’m interested in more than the human body. I’m interested in all of it, everything you can touch and see. And more—I’m interested in the soul, too. The spirit.”

“That seems very admirable,” she said, but sounded tentative, as though she wasn’t sure why anyone would be interested in such a strenuous undertaking. “But why does that mean you cannot wed?”

“Because I’ll be traveling. I wish to meet the greatest thinkers alive. I can’t remain here, in some palazzo in Venice, and expect all the wonders of the world to come to me,” he explained.

She seemed to consider what he said seriously, rocking a little side to side. “And you wouldn’t take your wife with you on your travels?”

He looked down on her gravely. “It wouldn’t do. Besides, a woman doesn’t want to go traveling. She needs a home where she can raise her children. That’s what makes a woman happy.” He recalled overhearing his mother saying this to his father once, when the duke had been preparing to follow the king of Hungary into battle. It promised to be a prolonged siege and he wanted her to travel with him. She’d laughed at the notion and suggested he bring one of his favorite mistresses instead. It had saddened his father, because he had truly loved her.

“I suppose that is true,” she said, giving in. “In all honesty, I cannot see myself living out of trunks. I will let my godfather know of your feelings. But you should be aware—the doge has been in on this plan from the beginning. He would like to see you wed and settled.”

“I know.”

“He’s sent some of his men to round up your friend, do you know that, too? That’s why he asked my godfather to have this dinner party for you tonight—so you would be occupied elsewhere when they went to arrest him.”

His heart seized in terror. He gripped Elena by the shoulders. “Who? Who are they going to arrest?” he asked, but in his heart he already knew. Who else could it be but Cosimo?

Her eyes went wide. “I didn’t hear the name. But he said the doge had you followed, to see where you disappeared to at night, and that’s how they found out what you were up to.”

His last visit to Cosimo—that had to be when he’d been followed, after he’d foolishly allowed himself to believe that he’d deflected the doge’s suspicions. Zeno had probably dispatched a spy to shadow him from that moment forward. With a sinking heart, Adair dashed out of the hall, bellowing for his cloak and hat. As he ran from the bishop’s palazzo and down the empty alleys, he began to realize that he was too late. It would be useless for him to go to Cosimo’s house now: no doubt they’d arrested him already. He would be on his way to the dungeon. This was terrible and it was all his fault; he’d underestimated Zeno, thinking him an impotent old fool who didn’t care what was going on right under his own roof. He’d made a ridiculous mistake, the kind of mistake made by headstrong young men, and now Cosimo would pay with his life.

Then another thought came to him, terrible in its meaning: the inquisitors would seize everything in Cosimo’s house that could be used against him as evidence for the trial. His magnificent collection of books would be destroyed, put to the torch after the trial was over. The loss staggered him. He ran even faster, not sure what he would do when he got there.

Just as he’d expected, the arrest had already taken place. Cosimo was gone, his servants huddled out on the square in their bed clothes, crying. The front doors were thrown open to the street, flanked by a few of the doge’s guards. They crossed their lances to bar Adair’s way when he ran up to them.

“You will let me pass. The doge has sent me,” he roared at the guards. He knew what he was doing was ill advised; he’d already gotten in enough trouble, and by declaring himself so boldly to the guards, the doge would certainly hear of it. But Adair could see no other way to gain entry to Cosimo’s house, and every moment was precious. “That’s right.” Adair turned and shouted at the mage’s servants, pretending to gloat. “It was all a trap set by the doge, and I was part of it. It was I who led them to your master. It is incumbent upon the doge, the leader of this city, to root out evil and eliminate it from our midst. Your master is evil—truly an evil man, a priest of Satan, and so I will testify at his trial.” He turned back to the guards and pushed the lances aside. “Now, out of my way. I tell you, I have been sent here by the doge himself and he will not tolerate your interference.”

His theatrics worked and they let him pass. Inside, every torch and sconce in Cosimo’s palazzo was lit and burning brightly. He heard the echoes of men’s voices coming down the hall from the study, and his heart sank. The inquisitors were here. As he approached the doorway, he saw two men standing before the shelves, thumbing through books. The floor was covered with discarded tomes and scattered sheets of paper. The men were dressed in the black robes of the court. Of course. Adair realized then that soldiers had not been sent to secure the documents because soldiers wouldn’t be able to read. These were two officials and they had already made two high piles of books on the floor, ostensibly to be taken away for further review.

He looked at the books thrown to the floor, and the few still clinging to the shelves like birds too frightened to come down from the trees. It seemed an unconscionable waste for all these books to be destroyed, a calamity on par—in Adair’s mind—with the destruction of the library of ancient Alexandria. He felt that he had to do something, salvage whatever he could. Out of the corner of his eye, he caught sight of the peacock-blue spine of the book he’d surrendered to Cosimo. A wave of sorrow passed through him for having to lose it a second time. Surely there had to be a way to save it.

He pulled back into the shadows before the two officials could see him, and tiptoed to the kitchen. The kitchen fire blazed untended, no doubt deserted by the servants when the soldiers burst into the palazzo. There was a stack of firewood next to the hearth and a box of kindling. Platters of roasted meat stood on the table, left pooling in fat. The entire room seemed smoky and greasy and combustible, an accident waiting to happen.

It would be an extreme measure, to burn the house down. But when the officials ran outside to escape the flames and smoke, Adair thought he might have time to rescue a few of the volumes. Was it better to set fire to the house than to let the books fall into the church’s possession? He wasn’t sure. The church might burn them, too—but there was a chance they might be spared for further study. As long as the books were intact, there was a chance they might eventually find their way back to a practitioner, someone who would benefit from their knowledge. If they burned, they were just ash.

The thought that the church would decide the books’ fate was too much for Adair to stand. To have these precious books rounded up like children and held hostage in trunks in a moldy basement at the duomo, rotting away day by day until they were nothing but mildewed pages stuck together, illegible . . . then thrown into the fires of the auto-da-fé, fuel to burn some poor luckless devil to death. No, he wouldn’t let that happen. He took some kindling and dipped it in goose fat, then held it to the flame. The tender wood caught quickly. From there it was a simple thing to creep down the hall and hold the flame to the hem of a dusty drapery. . . .

The house filled with smoke in minutes as flames leapt from wall to wall. Cries of alarm sounded from Cosimo’s study and then the two officials ran out, calling for the guards to fetch water from the well. As he ducked into the study, Adair knew he had mere minutes to act—and what’s more, the fire had leapt to the shelves quickly, seeming to know there were thousands of dry pages to feast on. Smoke had already engulfed the room and Adair could barely see his hand in front of his face.

Which books should he save? For a moment, he was paralyzed with indecision. It wasn’t as though he had Cosimo’s encyclopedic knowledge of the collection; he’d be hard-pressed to say which was the most valuable. He wanted to save them all but knowing that he couldn’t, his hand went to the one book that his eye always sought first: the one with the peacock-blue cover. Holding his hand over his mouth against the smoke, his eyes tearing, he grabbed the books on either side, too, and tucked all of them under his arm. He kicked open the shutters on the nearest window and—since he didn’t dare use the front entrance for fear of running into the soldiers’ bucket brigade—he hurled through the open window into the alley, landing in a puddle of filth. He leapt to his feet and ran without looking back, knowing that his mentor’s priceless collection was going up in flames, and by his hand.

Adair ended up hiding two books in a nearby square: all three made for too conspicuous a bundle to carry into the doge’s palazzo. And as little as he wanted to, he realized that he had to return to Zeno’s house. He would’ve tried his luck living on the street, selling his finer pieces of clothing to raise money to live on—at least he would be free—but he couldn’t bear the thought of giving up all those recipes he’d copied out by hand and hidden in his bedchamber. He decided to take his chances weathering the doge’s wrath. If Cosimo had been arrested for being a magician, it seemed to Adair that he had no chance of escaping the same fate. If Cosimo was going to burn, Adair stood a good chance of burning, too.

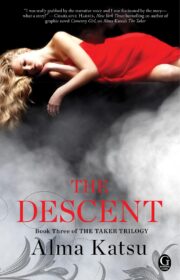

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.