Immortality had made me less human. Instead of giving me greater perspective on what it meant to be human, which you’d think would happen when you had such a long life, immortality had put me at a greater distance. No wonder Adair grew to be insensitive to the suffering of others: immortality forces you to become something other than human. I felt it happening to me, even though I didn’t like it. I came to see it was inevitable.

That night as I lay in bed, I thought back to one afternoon in the hospice. The doctors didn’t expect Luke to last more than a couple of days, and he was unconscious most of the time due to the morphine drip easing his pain. He wore a knitted cap for warmth as almost all his hair had fallen out from chemotherapy. What was left had turned shock white. He’d lost a lot of weight, too. His face was shrunken like an old man’s and his arms seemed too thin for the IV needles and the sensors that fed his vital signs to the monitors.

I’d taken to curling up in a lounge chair by the window, reading or knitting while he slept. I was grateful for the sedatives and painkillers making his last days more comfortable. After all, I’d sat with loved ones dying of tumors and tuberculosis with nothing stronger than Saint-John’s-wort and fortified wine to see them through it. The nurses, when they came in to check on him or change the drip bag, would invariably comment on my seeming calmness—backhanded compliments all; I think they thought I should be more upset, like Tricia and the girls. They couldn’t understand how I could be so detached. I’m sure they thought me cold-blooded. I wondered if Luke thought so, too.

This one afternoon, however, Luke was more lucid than usual. When I saw him shift restlessly in bed, I put down my book and went over to him. “How are you feeling?” I asked, taking his hand gingerly to avoid jarring the IV needle.

His eyes were feverishly bright. “I have a question for you. Are we alone?”

I looked through the open door toward the nurses’ station down the hall. They were engaged in their work. “Yes. What do you want to ask?”

He licked his lips. He seemed to be looking past me, as though he could no longer focus his eyes. “Lanny, I was wondering, now that I’m dying . . . if you had the power, would you make me like you?”

I hated that question. It wasn’t the kind of thing I would have expected from Luke, either. He’d always seemed too sensible, too down-to-earth. I tried not to miss a beat, however. “But I don’t have the power. You know that. . . .”

He was impatient with my evasiveness. “That’s not what I asked. I want to know if you would.”

I reached up to tuck a few loose white hairs under his cap. “Of course I would, if that’s what you wanted.”

He snorted and closed his eyes. “You’re just saying that.”

“Where is this coming from?” I asked, trying not to sound as tired as I felt. I knew why he was being peevish: he was afraid and exhausted. It was the end. It hovered in the darkness every time he closed his eyes. The waiting could bring out the worst in people.

His breath grew louder, ragged. “You know who could make me like you. Adair. He’d do it if you asked him.”

This time, I paused. Was Luke asking me to track down Adair and beg him to give me the elixir of life? It made me see Luke in a completely different light. Not only had I never suspected that he cared about living forever, I thought he would have sooner chosen death than ask me to go on his behalf to this man who frightened me so much. But death plays us cruelly at the end. “Is that what you want?” I asked, waiting.

But he’d slipped into unconsciousness. His hand went lax in mine. By the time he woke a few hours later, he’d forgotten ever asking me and I was spared from having to come up with an answer.

I remembered Luke’s question that night in the fortress, though, as I tossed and turned in bed. For here I was at Adair’s house not for Luke’s sake, not to beg for Adair’s favor so that Luke could spend eternity with me, but to ask him to help Jonathan, a man who was dead and gone and surely beyond our help.

And I did not want to ask myself why.

The house was very quiet when I rose the next morning, though I wasn’t surprised, not after listening to women’s voices and squeals of delighted laughter late into the night. I trotted down the stairs to the kitchen and made coffee, looking forward to time alone to sort out my thoughts without being reminded that Adair was finding ways to pass the time without me. My disappointment was understandable, then, when I found Terry lounging at the old farmhouse table in a pair of men’s pajama bottoms and a tank top too small to do much besides decorate her breasts. As the coffee brewed, she watched me out of the corner of her eye and popped tangerine segments into her mouth. Once the coffee was ready, I slid into a chair opposite her with a mug in my hands.

“There’s coffee,” I said, to be sociable.

She said nothing.

“It’s a lovely day,” I tried again, taking a sip from my mug.

She snorted and tore off another segment. “It’s bloody windy and cold, same as it is every day.”

“At least it’s sunny.”

“It is that,” she said, looking down at the tangerine peels, flicking them with a fingernail. Then she fixed her merciless stare on me. “So, don’t take this the wrong way . . . it’s not that Robin and I aren’t delighted to have you stay with us so completely out of the blue and all. But what made you decide to come looking for Adair, anyway?”

I could’ve pointed out that it wasn’t her house and it didn’t matter what she and her friend thought of me, but I reminded myself to look at it from her point of view. They’d all been having a wonderful time until I showed up. “I got the urge to see an old friend,” I said.

“Old friend, eh? How far back do you go, you and Adair?” Okay, that probably was the wrong excuse to use with her, given that I looked to be in my early twenties on the outside, and Adair not much older than that. As a matter of fact, we both appeared to be younger than Robin and Terry. “Are you childhood friends, then?”

“He was one of my first lovers.” It was the truth; I hoped that by letting her know we were intimate once but no longer would satisfy her. There was a time, in the beginning, when life with Adair had been thrilling. When I came to him, I was a young girl from a small, isolated town of people with Puritan forebears. I had been raised to work hard, not to question either my elders or the Bible, and to have few expectations of life. I knew nothing about desire or physical pleasure. Life under Adair’s roof turned all that upside down. Adair taught me about pleasure and showed me that it was possible to enjoy my body as well as other things in life—beautiful clothes, a fine wine, a good book, gay company—things the good folk in St. Andrew would’ve condemned as frivolous. To want such things was a sign of moral weakness. Life hadn’t always been easy in Adair’s house, but had it been any harder than the life I’d had in St. Andrew? I looked up to find Terry regarding me hostilely and added, “I haven’t come back for him, if that’s worrying you. I swear.”

Her aggression subsided upon hearing this. “I know I’m being awfully rude. It’s just—we’re having a good time here. And I’ve gotten very fond of Adair. Still, we know fuck all about him—he won’t talk about himself at all. We’d like to know more.” Her tone took on a conspiratorial warmth.

“There’s not much I can tell you,” I said, conscious that I was walking a tightrope. Adair didn’t like to be talked about behind his back. He’d impressed upon all his creations, we immortals, that we were never to share our secret with anyone outside our circle or risk terrible consequences. The result was that I tended to be tight-lipped around people. I saw in Terry the same frustration I’d seen in my friends over the years. They’d been hurt by my wariness and unable to understand why I put a barrier between us. I hadn’t been able to get close to anyone in a long time—until Luke.

I think Terry was starting to realize that what she had with Adair was all she’d ever get. It would never go on to greater intimacy; he would never let her get truly close to him. Now here I was—the first person from his past to show up on the island and probably the last. I was her one opportunity to learn more about the man she loved and, as much as she disliked me, she weighed the benefit and risk of sharing her fears with me. She nervously jammed her hands between her knees like an anxious child, before she spoke. “It’s been fun staying here with him, you know? He’s a good bloke, and we’re having a fine time, all carefree and easy. And it’s a nice place to live, isn’t it? Better than some filthy youth hostel. We thought we’d only crash here for a short while, Robin and me. That was the plan, anyway. We stayed for the laughs and”—her eyes flitted over my face—“good sex. It wasn’t love at first sight or anything. Things have changed, though. We feel differently now. He grows on you, doesn’t he? He’s so mysterious, and smart—and dead sexy, too. I’ve never met a man who could do the things he does in bed. . . .” She caught herself and gave me a brief, embarrassed smile. “Let’s just say they don’t make them like that in Bristol, where we come from.”

“They don’t make them like him anywhere,” I offered.

“Which is why we figured you came to get him back.”

I shook my head. “Adair and I found out the hard way that we’re not right for each other. We’re just friends.”

“If you say so . . .”

“Look, he’s wonderful—in some ways. He’s all the things you said of him, but there’s more to Adair than meets the eye. I’m not trying to talk him down, but . . . you can trust me on that.”

I was trying to convince her that she had nothing to fear from me, but everything I said seemed to have the opposite effect. Maybe she thought I was being patronizing, maybe she thought I was trying to trick her, for she jumped off the stool, bristling. “You talk like you’re done with him, but you’re not. I can tell. I can see it in your eyes plain enough, and if you really believe what you just told me, you don’t know your own mind. You’re fooling yourself if you think it’s over between you.”

“You’re wrong, Terry,” I said, trying to calm her, feeling as though I’d been pushed into a fight I didn’t want. “I’m not trying to come between you and Adair. You’ll see: once I’m gone it will go back to the way it was, and you two will have Adair to yourselves.”

She tossed back her hair, defiant. “Oh no, it won’t. Everything’s changed. Can’t you feel it? The minute you walked into the house it’s like something came between us, me and Robin and Adair. And it’s because he’s still in love with you—but you don’t need me to tell you that. You know it already.” Her face was flushed; her anger rose up like a storm inside her, fighting to get out. She looked at me sharply one more time, hatred in her flashing eyes, before bolting from the room.

It took a few minutes for me to calm down after Terry left. The house fell silent again. I sat at the table listening for noises from the floor above, straining for some sign that Adair had risen. I waited patiently until, sip by sip, I’d emptied my cup. Still, there was no indication that he was about to come downstairs. Restless, I decided I might as well go exploring.

To say the house was peculiar would be an understatement. It seemed to have once been a fort before it was converted into a residence. The house was deceptive; like a handkerchief tucked up a magician’s sleeve, you didn’t know what might be hidden inside. From the outside it looked small, but inside was another matter. As I meandered down long, lonely hallways and went up and down winding staircases, the house seemed to unfold continuously before me as though it sprang to life from an M. C. Escher design. As best I could tell, the house’s four wings made a perfect square, with a courtyard at its center.

On the first lap, I managed to lose my way somehow, and though surprised, I was amused by my inattention. However, it stopped being funny when, on the second lap, I still hadn’t found my starting point. By the third lap, I was near panic, thinking I might never find my way through this strange, telescoping maze. That is, I think I made several laps of the building, but I couldn’t be sure because I never seemed to take the same hall twice. Nor could I reliably say how many floors there were, or if these were floors in the conventional sense, as some staircases were only a half flight in length before stopping abruptly and leading to yet another hallway.

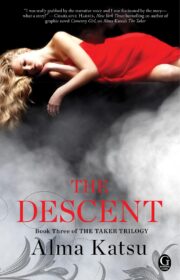

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.