The door shut. I was out of bed and saw to my relief that I could lock the door. I did this and immediately felt safe.

Then I lay in bed wondering why she had come to me. If I had taken her draught I should have been asleep. What would have happened then?

Sleep! How I longed for it! How I wanted to escape from my tortuous thoughts that went round and round in my head reaching no conclusion.

My only inference was: There is danger close-and particularly close to me. From whom does it come? And why? “

I lay waiting for the dawn and only with the comfort of daylight could I rest.

III

Three days later the Comte sent for us. Margot and I were to leave for Paris without delay.

I was not sorry to go. The mounting tension in the chateau was becoming unbearable. I felt I was watched and would find myself looking furtively over my shoulder whenever I was alone. I noticed that the servants regarded me oddly. I felt very unsafe.

Therefore it was a great relief to receive the summons.

It was a hot June day when we set out. There was a stillness in the air which in itself seemed ominous. The weather was sultry and there was thunder about.

The city had lost none of its enchantment, though the heat was almost intolerable after the freshness of the country.

I immediately noticed that there were numerous soldiers in the streets-members of the Swiss and French Guards who formed the King’s bodyguard. People stood about at street corners but not in large numbers. They talked earnestly together. The cafes, from which came the delicious smell of roasting coffee, were crowded. People overflowed into the streets where tables under flowered sunshades were placed for their convenience. They chattered endlessly and excitedly.

In the Faubourg Saint-Honore the Comte was waiting for us with some impatience.

He took my hands and held them firmly.

“I heard what happened,” he said.

“It was horrifying. I sent for you immediately. You must not return to the chateau until I do.” He seemed then to be aware of Margot.p>

“I have news for you,” he said.

“You are to be married next week.”

We were both too astounded to speak.

“In view of the state of-‘ the Comte waved his hands expressively everything, the Grassevilles and I have come to the conclusion that the marriage should not be delayed. It will necessarily be a quiet wedding. A priest will officiate here. Then you will go to Grasseville and Minelle will go with you … temporarily … until something can be arranged.”

Margot was delightedly astonished and when we went to our rooms to wash off the stains of the journey she came to me at once.

“At last!” she cried. There was no point in waiting, was there? It was all so silly. Now we shall leave here. My father will no longer be able to command me. “

“Perhaps your husband will do that.”

She laughed slyly.

“Robert! Never. I think I shall get on very well with Robert. I have plans.”

I was a little uneasy; Margot’s plans were usually wild and dangerous.

The Comte asked me to go to him and I found him in the library.

He said: “When I heard what had happened I was overcome with anxiety.

I had to find some way of bringing you here. “

“So you arranged your daughter’s marriage?”

“It seemed as good an answer as any.”

“You use drastic measures to get your way.”

“Oh come. It is time Margot was married. She is the sort who needs a husband. The Grassevilles are a family who have always been popular with the people … though how long’ that popularity will last, who can say. Henri de Grasseville S was a father to his fiefs and for that reason it seems difficult” , to imagine their turning against him.

They might, though,”;

in their present mood. Fidelity is not a noticeable quality among people now. They bear grudges more readily than gratitude. But I should feel happier if you were there. “

“It is good of you to be so concerned.”

“As usual, I think of my own good,” he said soberly.

“Tell me exactly what happened in the lane.”

I told him and he said: “It was a peasant taking a pot shot at someone from the castle and it happened to be you. It’s a step in a new direction for them. And where did they get hold of the gun? That’s a mystery. We are making sure that no firearms get into the hands of the rabble. That would be fatal.”

Is the situation deteriorating? ” I asked.

“It is always deteriorating. Each day we step a little nearer to disaster.” He looked at me earnestly.

“I think of you all the time,” he said.

“I dream of the day when we shall be together. Nothing … nothing must stand in the way of that.”

“There is so much standing in the way,” I said.

Tell me what. “

“I don’t really know you,” I answered.

“Sometimes you seem like a stranger to me. Sometimes you amaze me and yet at others I know exactly how you will act.”

“That will make life exciting for you. A voyage of discovery. Now listen to my plans. Marguerite will marry and you will go with her. I shall visit you at Grasseville and in due course you shall be my wife.”

I did not answer. I kept thinking of Nou-Nou at my bedside, of, Gabrielle LeGrand insinuations. He had murdered Ursule, she had hinted, because he was tired of waiting to marry her, Gabrielle. He wanted a legitimate son. Gabrielle had already given him that son; all that was needed was his legitimization which would be easy if they married. His idea according to her, was to lead me along so that I might slip into the re1e of scapegoat. She would probably suggest now that he had arranged that I should be removed from the scene. What if he had taken that shot at me . or arranged that it should be fired?

How could I believe that? It was absurd. Yet some instinct within me was warning me.

He put his arms about me and said my name with the utmost tenderness. I did not resist. I wanted to stay there in his arms and turn my face away from reason.

It was as though Margot hugged some secret to herself which was too precious to tell even to me.

I was amazed how easily she could throw off her troubles and behave as though they had never existed. I was glad she had had the good sense not to bring Mimi with her. Mimi might well have refused to come as she was now soon to be married and with Bessell to command her she could well have been truculent. The new maid Louise was middle-aged and glad to step into Mimi’s shoes. At the same time Margot had dismissed the conduct of Bessell and Mimi as though it were of no consequence. I wished that I could think so.

We had a busy week, mostly shopping, and once more I was caught up in the excitement of the city. I would watch from my window at two o’clock each day when the wealthy set out in their carriages to keep their dinner appointments. It was indeed a sight, for the ladies’ headdresses were becoming so outrageous as to be almost comical. Some would mince along balancing these confections on their heads which would represent anything from a bird of paradise to a ship in full sail. These were the people who aped the nobility-which was a dangerous thing to do these days. In the Comte’s household and others of its kind dinner was at six which gave time to go to the playhouse or the opera by nine o’clock which was the time when the city took on a different character.

We visited a private playhouse on one occasion to see a very special performance of Beaumarchais’ Le Manage de Figaro, a play which the Comte said should never have been shown at this time as it was full of sly references to the decadent society which were a delight to those who wished to destroy it.

He was thoughtful and moody as we returned to the hotel.

He had a great deal on his mind and was often away on court matters.

It touched me that, in view of all that was happening, he found time to plan for my safety, although, of course, I did not believe his daughter’s marriage had been arranged for that reason.

Robert de Grasseville with his parents and a few of their servants arrived in Paris.

In her excitement Margot looked so beautiful that I could almost believe she really was in love. Even though her emotions might be superficial, they were all-important to her while she felt them.

The marriage took place in the chapel which was situated at the top of the house. One left behind the luxury of the apartments, ascended a spiral staircase and stepped into an entirely different atmosphere.

It was cold there. The floor was of flagged stone and there were six pews placed before an altar on which was a beautifully-embroidered cloth and above it a statue of the Madonna studded with glittering stones.

The ceremony was soon over and Margot and Robert came out of the chapel together looking radiant.

Immediately afterwards we sat at table. The Comte at the head, his new son-in-law on his right hand and Margot on his left. I sat next to Robert’s father, Henri de Grasseville.

It was clear that the two families were delighted with the match.

Henri de Grasseville whispered to me that the young pair were undoubtedly in love and how gratifying it was to him that this should be so.

“Frequently in families like ours marriages have to be arranged,” he said. It so often happens that the partners are unsuitable. Of course they often grow together. They are so young when they marry they have much to learn and they learn from each other.

This is happy from the start. “

I agreed with him that the young couple were happy, but I could not help wondering what he would have felt if he had known of Margot’s experience, and I fervently hoped that all would go well, but I did feel uneasy remembering the demands of those two servants whom she had trusted.

It will be well to leave Paris soon,” went on Henri de Grasseville.

“We are peaceful at Grasseville. There has been no sign of trouble.”

I warmed to him. There could not have been a man less like the Comte.

There was something innocent about him. He looked as though he believed the best of everyone. I glanced along the table at the Comte’s rather saturnine face. He looked like a man who had gone through life trying all manner of adventures and had come through with his idealism tarnished if not broken. I felt a smile curve my lips and at that moment he looked at me, caught me watching him and there was a look of quizzical enquiry in his eyes.

When the meal was over, we all gathered in the salon and the Comte said he thought it would be wise to lose no time in leaving for Grasseville.

“One can never be sure from one moment to another when the trouble will begin,” he said.

“It only needs some small pretext to set it off.”

Oh, Charles Auguste,” laughed Henri de Grasseville, ‘surely you exaggerate.”

The Comte lifted his shoulders. He was determined to have his way.

He came to me and whispered: “I must see you alone before you leave.

Go to the library. I will join you there. “

Henri de Grasseville was consulting the clock which hung on the wall.

“If we are to go today,” he said, ‘we should leave in an hour. Will that suit everyone? “

“It will,” said the Comte, speaking for us all.

I went at once to the library. In a short time he was with me.

“My dearest Minelle,” he said, ‘you wonder why I send you away so soon.”

“I understand that we must go.”

“Poor Henri! He has little notion of the situation. He remains in the country and thinks that because the lambs still bleat and the cows moo as they ever did, nothing is changed. I hope to God he can go on thinking it.”

“His is a comfortable philosophy.”

“I see you are in the mood for discussion and you are going to say he is a happy man. He goes on believing that everything is good. God watches over us, and the people are kindly innocents. One day he will have a rough awakening. But, you will say, at least he was happy before it came. I should like to take you up on that but there is little time left to us. Minelle, you have never said you loved me.”

“I do not speak lightly of such emotions as you do, having made love to so many women. I dare say you have told people many times that you loved them when all you felt was a passing fancy.”

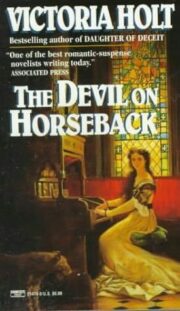

"The Devil on Horseback" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Devil on Horseback". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Devil on Horseback" друзьям в соцсетях.