They can’t have got far,” I said.

“They’ve got a start you know. They’ll bring them back mayhap … and what then?” She looked at me intently.

“They say it was to have been a match between her and Mr. Joel. That was why she was brought over here … least, that’s what I heard. What’ll happen now … who can say?”

“She is very young,” I said.

“I know her well … through school. I think she would be inclined to act recklessly and regret afterwards. I do hope Sir John is in time.”

“They say Mr. Joel is determined to stop the marriage. He’s gone off with his father. The pair of them will put an end to this, you can be sure. But what a scandal for the Manor.”

Anxious as I was to glean all the information I could, I was glad when Mrs. Manser left. I think she was trying to offer me some oblique warning, for it had been noticed that I sometimes rode out with Joel Derringham. Although there was not such a wide gulf between us as there was between Margot and her groom, still the gulf was there.

Mrs. Manser thought I should be wise to” encourage the courtship of her son Jim and learn to become a farmer’s j wife.

A whole day and night passed in anxious speculation and’;

then Sir John and Joel returned bringing Margot with them. I did not see her. She was exhausted and distraught and put straight to bed. No one called from the Manor to give me the news, and once again it was from Mrs. Manser that I gleaned information. ‘ “They found them in time. Traced them, they did. They’d covered more than seventy miles. I heard it from Tom Harris, the groom that went with Sir John. He likes a jug of our home-brew taken in the parlour.

He says they were both scared out of their wits and Master James wasn’t so bold when he was faced with Sir John. He’s been sent off on the spot.

That’s the last we’ll hear of James Wedder, I shouldn’t wonder. Not like Sir John to send a man off when he’s got nowhere to go to, but this was different, I reckon. This ‘un teach him a lesson. “

“Did you hear about Mademoiselle?”

Tom Harris said she was crying as though her heart was broken, but they brought her back . and that’s the end of James Wedder for her. “

“How could she have been so foolish!” I cried.

“She might have known.”

“Oh, he’s a dashing young fellow and young girls when they fancy themselves in love don’t always give much thought to what’s coming of it.”

Again I felt she was warning me.

Life was changing rapidly my mother gone forever and new responsibilities crowding in on me. The school was not the same; it had lost the dignity my mother had given it. I was well educated and could teach, but I seemed so young and I knew there was not the confidence in me which my mother had inspired. I was only nineteen years old. People remembered this. I found taking class more difficult than it had been there was a certain amount of insubordination. Margot had not come back to school although Maria and Sybil had. Maria told me that at the beginning of the summer she and her sister were going to a finishing school in Switzerland.

My heart sank. Without the Derringham girls, the school would lose the pupils who came from the Manor the preserve on our bread, as my mother had called them. But it was not so much the preserve I had to worry about as the bread itself.

“There is talk of our brother’s going on the Grand Tour,” Maria told me maliciously.

“Papa thinks it will be a good education for him and all young men of his station do it. He will be going soon.”

It was as though Margot’s adventure with the groom had set something in motion, the subject of which was to change everything.

I felt a sudden longing for Joel’s company he was always so calm, so reassuring in a way. And if he were going on the Grand Tour that meant that he would be away possibly for two years. What a lot could happen in two years! The once flourishing little school could become bankrupt. Without th Derringhams . what should I do? I felt I was being blame for Margot’s indiscretion. It had often been said that Marge and I were good friends. Perhaps it was also being said that had allowed myself to become too friendly with Joel Derringham - a liaison which could not have an honourable ending and that had been a bad influence on Margot.

When two girls from one of the nearby big country house announced that they were leaving and going to a finishing school it was like a red light flickering at the end of a tunneI took Dower out for a long ride hoping to meet Joel an hear from his own lips that he was going away. But I did not see him and that in itself was significant.

On a Sunday morning he came to see me. My heart started to beat faster as I watched him tether his horse. As he cam into the sitting-room he looked very grave.

“I’m going away shortly,” he told me.

There was silence broken only by the ticking of the grandfather clock.

“Maria mentioned it,” I heard myself say.

“Well, of course it is considered to be part of one’s education.”

Where shall you go? “

“Europe … Italy, France, Spain … the Grand Tour.”

“It will be most interesting.”

“I would rather not go.”

Then why? “

“My father insists.” ;

“I see, and you must obey him.” “I always have.” “And you couldn’t stop doing so now, naturally. But why should you want to ?”

“Because … There is a reason why I don’t want to g< He looked at me steadily.

“I have prized our friendship.” j “It was good.”

“Is good. I’ll be back, Minella.”

“That will be in the future.”

“But I shall come back. Then I shall talk to you … ver seriously.”

“If you come back and I am here I shall be interested t hear what you have to say.”

He smiled and I said quietly: “When do you leave?”

“In two weeks’ time.”

I nodded.

“Can I get you a glass of wine? My mother’s speciality. She was proud of the wines she made. There is sloe gin too. It is very palatable.”

“I am sure it is, but I want nothing now. I just came to talk to you.”

“You will see some glorious works of art … and architecture. You will be able to study the night sky in Italy. You will learn the politics of the countries through which you pass. It will be an education.”

He was looking at me almost piteously. I thought that if I made a certain move he might suddenly come to me and put his arms about me and urge me to be as foolish and reckless as Margot and her groom. I thought: No. It is not for me to lead the way. If he wants to enough he must do that. I wondered what the Derringhams would do if Joel told them he wanted to marry me. A second disaster and so similar to the other. A mesalliance, they would call it.

Oh my dear mother, how wrong you were!

“I shall see you before I go,” he was saying.

“I want us to ride out together. There is so much I want to discuss.”

After he had gone I sat at the table thinking of him. I knew what he meant. His family, realizing his interest in me, were sending him away. Margot’s episode had alerted them to danger.

Over the mantelpiece hung the picture of my mother which my father had had painted during the first year of their marriage. It was wonderfully like her. I gazed at those steady eyes, that resolute mouth.

“You dreamed too much,” I said.

“It was never meant to come to anything.”

And I was not sure that I wanted it to. All I knew was that my world was collapsing about me. I could see the pupils drifting away and I felt lonely and a little afraid.

Joel left and the days seemed long. I was glad when school was over though I dreaded the long evenings when I lighted the lamps and tried to occupy myself with preparations for the next day’s lessons. I was grateful for the frequent company of the Mansers, but I was always aware of Jim and their expectations with regard to him and me. I fancied Mrs.

Manser was telling her husband that I had come to my senses and stopped thinking of Joel Derringham.

I was deeply regretting the loss of our savings. There were several lengths of expensive material in my mother’s bedroom and the cost of keeping Dower had to be considered. I could not get rid of dear Jenny who had served us so well, so there were two of them to keep.

Maria and Sybil talked constantly of their approaching departure for Switzerland and I was haunted by the fear that I was not going to be able to keep the school going.

When I was alone at night I would imagine my mother was there and I would talk to her. I used to fancy I could hear her voice coming to me over that great void which separates the dead from the living, and I was comforted.

“One door shuts and another opens.” She had a stock of such well-worn truisms at her disposal to bring out when they fitted the occasion, and I had often teased her about them. Now I remembered them and rejoiced in them.

There was one thing which alarmed me and that was the new coolness of Sir John and Lady Derringham towards me. They considered I had behaved in a most unbecoming manner by allowing their son to be attracted by me. I should have known better, and they laid the blame on me, seeing me, I was sure, as a scheming adventuress. Even though Joel had been sent away on his Grand Tour, I believe they had decided that I should be given no more chances to practise my wiles, which meant of course a withdrawal of their patronage. This was the most frightening aspect of the situation. My mother had constantly mentioned what great good had come to us through them, and I was wondering how long I could run the school at a loss.

One blustering March day Margot came to say goodbye to me. She looked subdued, but I detected a sparkle of mischief i in her eyes. It was a Sunday-a day when there was no school and I-‘ expected she had chosen it for that reason. “Hello, Minelle,” she said. “I am going home next week. I’ve come to say goodbye. ” I felt suddenly wretched. I had been fond of Margot and it i meant that everything and everyone I cared about was slip) ping away from me.

“This little episode-‘ she spread her hands as though to embrace the schoolhouse, myself and the whole of England ‘it is over.”

“Well, it has been an experience for you.”

“Sad, yes, and happy … and amusing. Nothing is all one of those, is it. There is always some of each. Poor James. I often wonder where he is. Sent away in disgrace. But he will find a new place … more girls to love.”

“And you?”

“I also.”

“It was a foolish thing to do, Margot.”

“Yes, was it not? Like most adventures, they are so much more fun to plan than to carry out. We used to lie under the hedge in the shrubbery and make plans. That was the best part. It was so dangerous.

I used to run and find him at every possible moment. “

“When you played hide and seek, even,” I said.

She nodded, laughing at me.

“Anyone might have seen us at any time. We both said we did not care.”

“But you were afraid of what might happen.”

“Oh yes. But I like to be afraid. Don’t you? Oh no, you are too righteous. Though what about you and Joel, eh? In a way we are in the same position … two of a kind, as they say, do they not? We both lost our lovers.”

“Joel was not my lover.”

“Well, he hoped to be. And you hoped. It made me laugh. You … the schoolmistress. Me … and the groom. It was a dance … the dance of the classes. Funny, do you, see?”

“No, I don’t.”

“You have become a true schoolmistress, Minelle. But we had fun together-and now I am to go back to France. Sir John and Lady Derringham have been longing to be rid of me and now I am going.”

“I am sorry. I shall miss you very much.”

She stood up and in her impulsive way flung her arms about me.

“And I shall miss you, Minelle. I always liked you the best. I cannot talk to Marie and Sybil. They look down their silly noses at me as though I have the plague … and all because I have known something which they have not … and never will, most likely. Perhaps you will come and see me in France.”

“I cannot see how this would be possible.”

“I might ask you.”

“It is kind of you, Margot.”

“Minelle, I am a little worried.”

“Worried? What about?”

“I don’t know what I should do.”

“Perhaps you should explain.”

“When James and I lay under the hedge in the shrubbery we did not simply make plans.”

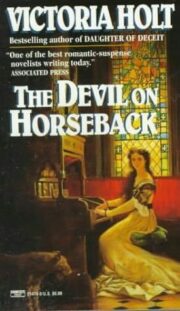

"The Devil on Horseback" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Devil on Horseback". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Devil on Horseback" друзьям в соцсетях.