He had meant to be stern. A man could not allow his wife to behave as Allegra had behaved, but at the touch of her lips he melted. He kissed her back. "I am a fool," he said, looking down into her eyes. "You have acted badly, and I should exercise my husbandly rights and punish you, Allegra."

"Ohh, yes, my darling, you should," she agreed.

"Did you even get as far as London?" he demanded, suspicious of her charming and adorable mood.

"Oh, I did. I went to a gambling house with Prinny and Mr. Brummell, and then the next night I went to Vauxhall with them. It was lovely, Quinton. I couldn't do those things as a debutante, and we didn't do them when we were all in London last winter. It was very exciting, my darling, but that is not the best thing of all."

"How much did you lose, Allegra?" he demanded, his gray eves suddenly icy.

She laughed. "Oh, Quinton, I am not such a turnip-head as that. I took a thousand pounds with me, and decided that when I had lost it I should come home. After all, I have no desire or passion for gambling. But the oddest thing happened. I could not lose. Whether it was at Hazard, or Whist, or E.O., I could not lose. I won over fourteen thousand pounds in a very short time. I think the proprietor of Casa di Fortuna was happy to see me leave,” she finished, giggling.

"And what did you do with the monies you won, Allegra?" he asked, but his tone and his manner had softened.

"I gave it to Charles Trent to invest. When our eldest son is of age he shall have half of it for himself, and the other half we shall use for our eldest daughter's season and marriage portion, she told him with a smile. "I think the first son and the first daughter are always the most special. Oh," she said suddenly. "I have a new brother. He was born two days ago. They are calling him William Septimius James, and he is absolutely gorgeous! He looks just like Papa. My brother, James Lucian, never did you know. He favored our mother."

She was like a fountain, the words pouring forth from between her pretty lips. He felt his anger and suspicion dissolving.

"My marriage portion, of course, will be considerably constrained," she chattered on at him. "After all, Willy is the heir now, and I am just his elder sister. We shall not have five hundred thou-sand pounds a year anymore, Quinton. But did you not tell me it didn't matter?"

She was testing him, he knew. "It does not matter," he told her firmly. "The only thing I want of Lord Morgan is his daughter," he said.

"You are very sweet, my darling," she told him, "but not very practical. You shall receive one hundred thousand pounds each year, and I shall inherit a quarter of Papa's estate when he dies, which, God willing, will not he for many years. You will, however, have to give me my pin money out of that, Quinton, for I shall receive no other stipend. I do not need it as I have my own monies, and 1 have you for my husband." She smiled up at him proudly. "Have I made us a good bargain, husband?"

He nodded, slowly, surprised at how efficiently she had managed everything once again. Then he shook his head. Why was he surprised? From the moment he had agreed to marry her, Allegra had managed everything, and she was far more adept at it than he ever was. She would probably manage him for the rest of their days, although he would never admit it to his friends. He took her hand in his, and together they walked into the house. "Having won all those monies, are you still of a mind not to gamble?" he asked her.

"It was beginner's luck, or so the Italian contessa I met that night said. No, I do not believe I shall ever gamble again, sir," Allegra told him sincerely.

"And you liked Vauxhall?" he queried.

"It was interesting, especially the Cascade, but there are far more beauties of a natural sort in the countryside. I suppose it is fine for city folk, Quinton. I did enjoy the concert in The Grove, but the supper. It was shockingly expensive! Why Mr. Brummell said that the carver at Vauxhall has been known to slice a whole ham so thin you could paper the entire gardens with it! And the cheese was dry, I fear, and the Arrack punch they served was quite nasty. I do not need to go back again," Allegra told her husband.

"I am relieved to hear it as we shall have to scrimp to get by on one hundred thousand pounds a year," he teased her, and then he lifted her up, and kissed her happily. "I thought you might not come back to me, Allegra," he told her.

"You thought no such thing, flatterer," she laughed, but his bald-faced lie had sent a thrill through her right down to her toes.

He set her down on her feet again. "I love you, Duchess."

"I am glad," she responded, "for it is important that children come from love, Quinton."

"Then you are ready to resume our efforts?" he said softly, kissing her lips once more.

"It is not necessary, sir," she told him, smiling happily into his eyes. "Lady Bellingham, our dear guardian angel, saw at once that my moods and crotchets were because I was ripening with your… our child, Quinton. Her own doctor has confirmed it. By year's end we shall have a son or a daughter, and Hunter's Lair will again ring with the laughter of children. I might even forgive Melinda and let her bring George's boy to play."

He felt as if his heart had suddenly swollen up, and when it burst his happiness was like a shower of stars. "Ohh, Allegra! You have made me the happiest of men." He lifted her up carelully, and then kissed her lips tenderly.

As he lowered her to the floor again she slipped her arms about him, and smiled into his eyes. "I love you, and after we have paid our respect to Papa and Aunt Mama, and you have admired Willy, I want to start our journey home, Quinton. And, my darling duke, I promise never to run away from you, or from our life together, again."

Both Lord and Lady Morgan were delighted to see Allegra and Quinton had reunited without difficulty. William Septimius James, a healthy, plump, pink infant with mild blue eyes, observed his elder half sister and his brother-in-law from the comfort of his mother's arms. As Allegra had told her husband, he was a miniature of his father, even to the shape of his head, which was covered in a dark down.

"I cannot wait until Sirena sees him," Allegra chuckled. "Now we are truly sisters."

"He'll make a fine playmate for his nephew," the duke observed with a broad smile. "What fun it will be in a few years' time to see all of our children playing together at family gatherings."

"If Gussie and his silly wife will allow my grandson to join us all, but Charlotte has wrapped the lad in cotton wool from the moment of his birth. Heaven knows what will become of him unless my son takes a stand. They need more children to take Charlotte's mind from the lad," Lady Morgan said firmly.

"I am going to take Allegra home now," the duke told his inlaws. "I think it is time she returned, and Hawkins is eager to have Honor home as well, you will understand. They'll be married on Sunday."

"Indeed, sir," Lord Morgan agreed.

Kisses and handshakes were exchanged all around. Then the Duke and Duchess of Sedgwick departed for their home. They made the trip a leisurely one, traveling through the bright May countryside. The orchards, just hinting at bloom when Allegra had left, had now burst into a pink, peach, and white glory. Cattle and calves grazed contentedly in the meadows. Sheep and lambs browsed upon the hillsides. Everywhere there were signs of burgeoning life, new life. This time the sight did not hurt Allegra's heart, for beneath it the heir to Sedgwick slept as he or she waited for the proper time to be born.

Hunter's Lair looked to her, as it had from the beginning, like home. Crofts greeted her smiling, as did the other servants. They quickly learned the duchess's happy news and celebrated it. Summer came, and the fields were green with the growing grain. Sirena and Ocky brought little Georgie to Hunter's Lair so he might be christened in the duke's own church as his godmother was not of a mind to travel now in her delicate condition.

Sirena had already traveled to Morgan Court, leaving Georgie behind with a wet nurse. "What do you think of our brother?" she asked Allegra. "He is quite your papa's image, isn't he? There seems to be nothing of mama in him at all, except perhaps his eyes, but only the color. The look is pure Morgan," she laughed. "Quite like you, Allegra."

Allegra laughed too. "I have not seen him in two months," she said, "but he did indeed look like Papa."

"They are so happy," Sirena noted. "They were before, but they are even more so now. I think it is having something they created and share together. I know Oeky and I feel that way about Georgie."

"I felt it move today," Allegra said to her cousin. “It was like a butterfly fluttering in my belly."

Sirena smiled. "Soon he will be like a horse, kicking and demanding to be let out of his confinement. At least that was how Georgie was with me. I want another."

The autumn came, and Allegra begun to grow rounder and rounder as the season deepened. Indeed she was larger than Honor, or even Lady Morgan had been, yet she seemed quite healthy. On the twenty-eighth of November, several weeks before she had believed the baby would be born, the Duchess of Sedgwick went into labor. The duke sent for Doctor Thatcher to come immediately.

Looking at herself in the full-length mirror, Allegra said, "I look like one of your mares about to foal. I will admit to being glad to be rid of this enormous burden. These last weeks have been awful. Why do not women speak on this instead of nattering on about all the delights of motherhood? So far I find no delight in at all." She winced as a wave of pain swept over her, almost doubling her over, an accomplishment in itself given the size of her belly.

"You don't make me feel like giving up my burden none too soon," Honor said, gazing down at her own girth.

The birthing room was well prepared with plenty of clean linens. The fireplace steamed with kettles of hot water ready for use when called for by the doctor. The ducal cradle adorned in satin and lace was ready for its occupant along with the proper amount of swaddling clothes for the baby. There was a basin set aside for cleaning the infant of blood. All waited upon the Duchess of Sedgwick to give up her baby.

"Ohhhh!" Allegra moaned, as another wave of pain washed over her body. "Damnit! Why does it hurt so, Doctor Thatcher?"

"It is a woman's lot, Your Grace," he answered.

"That, "Allegra replied, "is a most stupid answer."

The doctor looked startled at such a bold exclamation. He was used to birthing women either weeping piteously, or cursing out their husbands, or bearing their lot with dignity and stoicism.

"I believe, doctor, that my wife desires a more practical answer to her question," the duke said, close to laughter.

"Of course I do," Allegra said. "What causes the pain I am enduring now? Is the baby all right?"

"The pain, Your Grace, is caused by the spasms your body is making to help you expel your infant," Doctor Thatcher explained. "If they become too unbearable I can give you some laudanum."

"Would that not drug the child as well?" Allegra said.

"Well, yes, but…" He got no further.

"I will bear the pains," Allegra said. "Ohh hell, and damnation!"

Quinton Hunter burst out laughing, unable to help himself.

"Get out!" Allegra shouted at him. "You are responsible for my state, and I will not have you howling like a hyena at my distress. I will have them call you back when the child is born. Get out!"

"Duchess, I beg your pardon, but let me remain," he said.

"No," she said implacably. "You are banished, sir, and take poor Honor with you. She doesn't need to see this in her state."

Honor did not argue with her mistress. She hurried along after her master, saying as she went, "I'll wait in the salon, my lady."

"There, there, my lady," the housekeeper, Mrs. Crofts, said soothingly. "What do men understand? It'll all be over soon."

"Not soon enough," Allegra grumbled as her labors began in earnest.

After several hours the doctor saw the infant's head crowning, and so informed the duchess that her labors would shortly be at an end. The child's head and shoulders were born, and then as its little torso began to slip from its mother's body Doctor Thatcher gave a muffled cry of amazement.

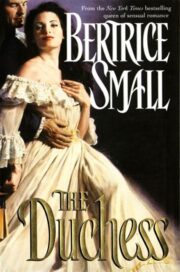

"The Duchess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duchess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duchess" друзьям в соцсетях.