“I’m sorry, Your Grace,” Joanna said as soon as they were alone. “But I know you saw that wink, and I wanted to explain to you, so as you’d not have the wrong idea.”

Eleanor looked her over. Joanna had black hair and blue eyes and was not long past her first youth, perhaps thirty at most. She had a winsome smile, and her eyes sparkled with animation.

“All right,” Eleanor said. “But first, I must ask you. What do you know about photographs?”

The maid’s smile deepened. “Many things, Your Grace. You got them, then?”

Eleanor stopped. “You have been sending me the photographs?” She thought of the ill-spelled missives, always with the closing, From one as wishes you well. The words went with the warm woman who stood before her now.

“Goodness,” Eleanor said. “You did lead me on a merry chase. Why did you send them?”

Joanna curtseyed again, as though she couldn’t help herself. “Because I knew they’d take you to him. And see—you’re married to him now, and he looks ever so much better, doesn’t he? Now about that wink, Your Grace, it don’t mean nothing. He does that because he’s a kindhearted man. It’s sort of a signal, a joke between us, really.”

“A joke.” This was the first time in memory that Eleanor had heard someone refer to Hart as a kindhearted man. “Has it to do with the photographs?”

Had Hart told Joanna to send them? It would be like him, to confound and tease Eleanor with the photographs and at the same time pretend he cared nothing about them. Hart Mackenzie needed a good talking to.

“No, no,” Joanna said. “Them’s two separate things. If you’ll listen, Your Grace, I’ll explain.”

Eleanor nodded, curbing her impatience. “Yes, indeed. Please do.”

“Blame my forwardness on me upbringing, Your Grace. I grew up in London, in the east part of it, near St. Katherine’s Docks. That was all right, but my father was a lout and a layabout and my mother didn’t amount to nothing, so we were poor as dirt. I decided I’d clean up and learn my manners and become a maid in a Mayfair household, maybe even a lady’s maid. Well, I didn’t know nothing about training or references, I was that green. But I did my best, and I went and answered an advertisement for a position. Name of the lady what hired me was Mrs. Palmer.”

“Oh, dear.” Eleanor saw a glimmer of what was coming. “You didn’t realize she was a procuress?”

“Naw. Where I came from, bad girls were obvious, flouncing about the streets and such, and what wicked tongues they had on them! But Mrs. Palmer spoke quiet like, and her house was large and filled with expensive things. I didn’t know at the time that ladybirds could be so lofty and thought I’d landed in clover. But that went away as soon as she took me upstairs, where she and another lady were in a bedroom. The things they told me they wanted me to do would make you faint, Your Grace. I might have grown up rough, but I was at least taught good from bad. So I said I wouldn’t, no matter how much they slapped me, and then Ma Palmer grabbed me and locked me in a room.”

Eleanor’s hands closed to fists, the pity she’d held for Mrs. Palmer, which had diminished over what the woman had done to Beth, diminished further. “I am sorry. Go on.”

“Well, Ma Palmer let me out again later that night. She said she had to get me cleaned up, because the master of the house was coming. I thought she meant her husband, and I couldn’t imagine what sort of man would marry someone like her. So there I was, washed and brushed, with a brand-new frock and cap, told I needed to bring the tea things into the parlor. Well, that didn’t sound so bad, and maybe Mrs. Palmer would behave herself in front of her husband. Cook put together the tea tray, and I made sure it was all pretty and carried it into the parlor. And he was there.”

Eleanor didn’t need to ask who he was. Hart Mackenzie, devastatingly handsome, arrogant, compelling.

“He were the most handsome gent I’d ever seen, and obviously so very rich. I stood there in the doorway, gaping at him like a fool. He gives me such a look, like he can see me inside and out, and gents like him aren’t supposed to even notice servants. At least that’s what I’d been told. I should be invisible, but he takes a long time to look at me. Then he sits down on the sofa, and Mrs. Palmer puts herself next to him, fluttering and cooing like a lovesick schoolgirl. She tells me to set down the tray on the table in front of them, and I tell you I was that nervous. I was sure I’d drop all the crockery, and then I’d be out on my ear.

“Ma Palmer laughs and says to him, Look what I’ve brought you. At first, I thought she meant the tea, then I caught on that she meant me.”

Eleanor remembered Mrs. Palmer confessing, her handsome face anguished, that she’d hired other women for Hart when she feared he’d grown tired of her. But Joanna hadn’t been a game girl, only a naive young woman trying to better her life. Eleanor’s pity for the late Mrs. Palmer diminished still more.

“I mean to tell you, Your Grace, I almost did drop all the tea things,” Joanna said. “It hit me like a blow that Mrs. Palmer had hired me to be a whore for her husband. I still thought he were her husband at that point, you see. I wanted to cry, or run back home, or even go for a constable. But Ma Palmer grabs me and whispers into my ear, He’s a duke. You do whatever he says, or he can make things very bad for you.

“I was that terrified. I believed her, because aristocrats, they do anything they like, don’t they? I knew a lad who used to be footman to one, and the lad got a beating whenever the lord was out of temper, didn’t matter that he wasn’t angry at the footman at all. I was sure Mrs. Palmer was right, and I was shaking in me boots, I can tell you.

“And then His Grace, he looked me over again and told Mrs. Palmer to get out of the room. She went, not looking pleased about it, but I realized, even then, that when this gent snapped his fingers, Ma Palmer jumped.

“Anyway, she left and closed the door. And there was His Grace, a’sitting on the sofa, looking at me. You know how he does. Steady like, as though he knows everything about you, every secret you ever had, and ones you didn’t even know about.”

Eleanor did know. The penetrating golden stare, the stillness, Hart’s conviction that he commanded everyone in his sight. “Indeed.”

“So, there I was. Well, Joanna, you’re in for it now, I was thinking. I’d be a ruined girl and never get a good place again. I’d be a whore the rest of me life, and that would be the end of it.

“His Grace just looks at me, and then he asks my name. I told him—weren’t no use in lying. Then he asks where I came from, and was this my first place, and what possessed me take a job with Mrs. Palmer? I told him I hadn’t known about Ma Palmer until I was already in the house. He looked angry, very angry, but I somehow knew he weren’t angry at me. His Grace told me to stay where I was, and he goes to the desk and pulls out some paper. He sits down and starts writing something, me standing there with my hands empty, having no idea what to do.

“He finishes up and comes back to me, handing me the folded letter. You take this to a lady I know in South Audley Street, he says. I’ve written the directions on the front. You walk out of this house and find a hansom and tell him to take you there. Tell the housekeeper in South Audley Street to give the letter to the lady of the house, and do not let her turn you away. Then he hands me shillings. I didn’t want to take them, but he said they were for the hansom. He told me not even to go back upstairs and get my things—such as they were.

“I was a little worried about where such a man as him would send me, but he gives me a stern look and says, She’s a lady, is Mrs. McGuire, a true lady with a tender heart. She’ll look after you.

“I started to cry and say thank you, and that he was being so kind. He put his finger to his lips and smiled at me. You’ve seen His Grace smile. It’s like sunshine after a wet day. And he says—I’ll never forget his exact words—Don’t ever say to anyone that I am kind. It will ruin my reputation. Only I will know, and you. It will be our secret. Then he winked, like he did when he came in tonight.

“I weren’t sure, even then, because I’d never heard of this Mrs. McGuire. It might be all a strange game he was playing with me. But I did what he said. He even walked me out into the hall and down to the front door. I should have gone out the back, being a servant, but he said he didn’t want me walking through the kitchens.

“Mrs. Palmer comes out while he’s taking me down the stairs. He gives me a little shove toward the front door, and then he turned on her. Right enraged he was. He shouted something terrible, asking Ma Palmer what was the matter with her, and Why would you think me depraved enough to want to deflower an innocent? Mrs. Palmer was crying and shouting back at him, and telling him she didn’t know I was an innocent, which was a lie, because she’d asked me. I ran right out of that house and let the door bang behind me, so I didn’t hear any more.

“Now, I could have taken the shillings and gone anywhere I wanted to, but I decided to take the hansom to South Audley Street and give the letter to Mrs. McGuire on the off chance.” Joanna spread her hands. “And here I am.”

The story sounded like Hart—he had an amazing sensibility about what people were like and who needed a hand up and who needed to be kept in check. That was how he’d risen so far, she thought, from a lad beaten by his father to a man knowing who to be gentle with and when.

“I still haven’t told you all of it,” Joanna said. “The next time I saw His Grace, he was paying a call on Mrs. McGuire, who is a good lady, just as he told me. When I took his coat, I made to say something to him, but he puts his finger to his lips again and tips me a wink. I winked back at him, and he went away. It’s become our signal, like, for me saying thank you, and for him keeping his good deeds secret. No one’s ever caught the signal, except you, tonight. Stands to reason you would, since you’re his wife. I wanted to tell you all about it, in case you misunderstood. And I’m married meself now,” Joanna finished proudly. “I have a son, five years old and he’s such trouble.”

Eleanor sat still after Joanna finished, thinking the story through. “You haven’t explained about the photographs. How did you get them? Did Hart himself give them to you?”

“His Grace? No. He knows nothing about them. They came my way about four months ago, around Christmas.”

“Came your way how?”

“In the post. A little packet of them, and I must tell you, I blushed when I opened them. It came with a note that told me to send them on to you.”

Eleanor’s eyes narrowed. “A note from whom?”

“Didn’t say. But I was told to send them to you one or two at a time, starting in February. I knew who you were, everyone does, and I thought it couldn’t do no harm. His Grace always looks sad, and it tickled me to think you’d maybe go and see him, and show him the piccies and make him smile. And you see? You married him.”

“But what about the others?” Eleanor said, her curiosity not abated. “Why were they sold to a shop in the Strand?”

Joanna blinked. “Others? I don’t know about any others. I was sent the eight, which I started sending on to you.”

“I see.” Eleanor thought about the sequence of events. Hart had proclaimed his intention of taking a wife to his family at Ascot last year in June. Joanna was sent the photographs at Christmastime, told to start sending them to Eleanor in February. Eleanor rushes to London to see Hart, Hart begins his game of seduction, and Eleanor now was his wife.

Planned by Hart from beginning to end? He was devious enough to do it.

“How do you know His Grace himself didn’t send you the photographs?”

Joanna shrugged. “Handwriting was different. I’d seen the letter he wrote to Mrs. McGuire.”

Hart might be canny enough to know that, perhaps get someone else to pen the note, not telling that person what it was all about. Eleanor might have to interrogate Wilfred.

“How did you know I’d gone to London?” she asked. “The second photograph reached me there, in his house.”

“Mrs. McGuire,” Joanna said. “She knows everyone. Her friends in London wrote her that you were in London, you and your father guests of His Grace in Grosvenor Square. I was serving tea one afternoon when Mrs. McGuire read the letter out to her husband.”

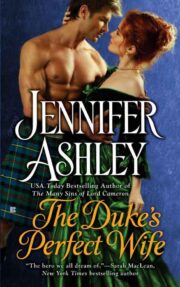

"The Duke’s Perfect Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.