“Why would I not care?”

The empty look in his eyes made Eleanor go soft. Going soft was dangerous around Hart Mackenzie, but drink had erased his hardness, letting her glimpse inside his shell.

She found it alarmingly blank. What had happened to him?

“You courted me to gain influence over my father’s connections and cronies,” she said. “I knew that. It is the same reason you married Sarah, and I imagine the same reason you’ll take your next wife. Whether or not I forgave you all your past sins might not have held the remotest interest for you.”

Hart came out of the chair. Eleanor backed away. She wasn’t afraid of him, but he was drunk, she knew she easily angered him, and Hart was a very large man.

“I told you,” he said. “Nothing I said to you while I was courting you was a lie. I liked you, I wanted you…”

“Yes, I did rather enjoy being seduced by you.” Eleanor held up her hand, palm out, and unbelievably, he stopped. “I forgave you, because we were both very young, very arrogant, and a bit stupid. But life moves on. I am likely one of the only people to know how much of a blow Sarah’s death was to you. And your son’s death. And, indeed, Mrs. Palmer’s. She was rather awful, and I am very angry with her for what she did to Beth and Ian, but I know you cared for her. Losing someone you’ve cared about for a very long time is quite painful. I do feel sorry for you.”

“Mrs. Palmer died two years ago,” he said rigidly. “We are still not up to the present day.”

“I am trying to explain. Why on earth would I think you would be pleased for me to turn up on your doorstep, bleating that I’d forgiven you? The photograph was a godsend, because it gave me the excuse to come here. I did not lie when I said money was a bit tight, so I thought I might as well ask you for a job to go with it. You gave me that hundred pounds last year, but such things don’t last forever, and the house needed many repairs. Going hungry so that your loved ones can eat sounds romantic, but I assure you, it quickly becomes tire-some. Your cook is quite gifted. I’ve feasted well these last few days.”

“Eleanor. Stop.”

“But you did ask me…”

“For God’s sake, will you stop?”

Eleanor blinked at him, but when he only closed his mouth, she drew a breath.

“Very well,” she said. “If you’d prefer me to be succinct, I am here because: item one, I need the position; item two, I’m annoyed that someone would try to hurt you by means of the photographs; item three, I would like us to be friends, with no hard feelings between us.”

Hart clutched the empty glass until the facets pressed into his fingers. Her eyes were enormous, blue like delphiniums in the sunshine.

Friends, no hard feelings.

She held out a salve, with a smile, offering peace. She knew more about him than anyone else in the world, including his brothers, and she’d just said she was sorry for him. Here he was, then, the beast in the tower with the princess petting his head.

“As for the photographs.” Eleanor’s voice cut through his drink-soaked brain. “Who knew about them besides you and Mrs. Palmer? I still think I ought to go to the house in High Holborn and look about, or talk to some of the ladies who used to live there—”

“No, you will bloody well leave it alone!”

Eleanor looked at him, her lips parted, surprise in her eyes, but no fear. Eleanor had never feared him, something that had amazed and intrigued the young Hart. The entire world thought him dangerous, unpredictable, terrifying, but not Eleanor Ramsay.

Now she was ripping the bandages off his wounds, making the blood flow anew, when Hart didn’t want to feel anything ever again.

“Eleanor, why are you in here, making me talk about all this? Making me think about it?” And he was too drunk to stop the whirling memories.

“Oh, dear.” She took a step toward him. “Hart, I am sorry.”

Eleanor reached for his hand. Hart felt the air between her fingers and his warm, as though they touched before the contact. Anticipation. He needed her touch.

Eleanor stopped the movement and let her hand fall, and something inside him screamed.

His idea that he could coolly court her again was insane. Hart could never be cool with her, never.

Eleanor said nothing. One red gold curl drooped over her forehead, the only strand not tightly braided in place.

Hart wanted to thread his fingers through her hair and pull it loose, feel it tumbling over his hands. He’d scoop her to him and stop her words with kisses. Not tender, sweet kisses but needy, demanding ones.

He needed to taste her, to find her fire, to not let her leave this room tonight. He wanted to loosen the prim bodice and scrape his teeth across her bare shoulder, wanted to leave his mark on her white throat.

He imagined the salt scent of her skin, her pleasant moan as he licked her, the dark jolt in his heart as she put her hands up to protest.

If he kissed her, he’d make her stay, have her bodice crumpled around her waist, her corset unlaced. He’d touch her in slow strokes, hands on her body, relearning her heat.

He’d held back with her when they’d been engaged, but Hart knew that if took her this night, he’d not hold back. He was drunk, frustrated, and in deep pain. He’d teach her things that would shock her, and he’d not let her go until she’d done them back to him.

His need tightened like a net around him, a need he’d not felt in years. His wild sexual yearnings had vanished into the vast emptiness that was Hart Mackenzie, or so he’d believed. That need snaked through him now and mocked his self-control.

The yearnings didn’t go away, he realized. They only went dormant. Until tonight when they were kicked into roaring by black-lashed eyes and a curl against a sweetly freckled forehead.

“Get out,” Hart said in a harsh voice.

Eleanor’s red lips popped open. “What?”

“I said, get out!”

If she stayed, Hart wouldn’t be able to stop himself. He was too drunk for control, and God only knew what he’d do to her.

“Gracious, Hart, you have turned hard.”

She didn’t understand how hard. Picturing himself pinning Eleanor on the bed, holding her by her wrists drawn over her head, feeling her soft breath while she moaned in pleasure—had him hard as granite.

“Get out, and leave me alone.”

Eleanor didn’t move.

Hart snarled, turned, and hurled his crystal goblet into the fireplace. Glass shattered and leftover droplets of whiskey sprayed, the fire catching them and bursting into tiny blue flames.

Hart heard Eleanor’s swift footsteps behind him, felt the draft as the door was flung open, heard the click of her heels in the gallery. Running. Away from him.

Thank God.

Hart let out his breath, closed the door, and turned the key in the lock. He moved back to the decanter and poured another large measure of whiskey into a clean glass. His hands were shaking so he could barely raise the glass to his lips to drink.

Hart opened his eyes to sunshine pounding through the window and a sound in his head like a saw scraping granite.

He was facedown on the bed, still in shirt and kilt, a whiskey glass an inch from his outstretched hand. The last swallow had spilled from it, leaving a sharp-smelling spot on his coverlet.

Hart’s mouth felt as though it had been stuffed with cotton, and his eyes weren’t focusing. He made the supreme effort of raising his head, and discovered that the sawing sound came from his valet, a young smooth-mannered Frenchman he’d hired when he’d promoted Wilfred, stropping a razor over a steaming bowl of water.

“What the devil time is it?” Hart managed to croak.

“Ten o’clock in the morning, Your Grace.” Marcel prided himself on speaking English with no trace of accent. “The young lady and her father are packed and ready. They’re downstairs waiting for the carriage to take them to the station.”

Chapter 4

Half of Hart’s staff looked utterly shocked to see His Grace charge down the stairs in kilt and open shirt, his face dark with beard and his eyes bloodshot.

They must not know him well, Eleanor thought. Hart and his bachelor brothers used to get falling-down drunk in this house, sleeping wherever they dropped. The servants either became used to it or found a calmer place of employment.

The servants who’d been with him a long time barely glanced at Hart, going on about their business without breaking stride. They were the ones who’d become inured to working for Mackenzies.

Hart pushed past Eleanor, his clothes smelling of stale smoke and whiskey. His hair was a mess, his throat damp with sweat. He turned in the foyer and slammed his hands to either side of the door frame, blocking Eleanor’s way out.

Eleanor had seen Hart this disheveled and hung over after a night of revelry before, but in the past, he’d maintained his wicked sense of humor, his charm, no matter how rotten he felt. Not this time. She remembered the emptiness she’d seen in him last night, no trace of the sinfully smiling Mackenzie who’d chased twenty-year-old Eleanor. That man had gone.

No. He was still in there. Somewhere.

Lord Ramsay said from behind Eleanor, “Eleanor has decided we should return to Scotland.”

The new, cold Hart fixed his gaze on Eleanor. “To Scotland? What for?”

Eleanor simply looked at him. The splintering of glass, the Get out! still rang in her ears. The words had cut her, not frightened her. Hart had been working through pain, and the whiskey had sharpened it.

Please, something in his eyes whispered to her now. Please, don’t go.

“I asked you, why?” Hart repeated.

“She hasn’t given a reason,” Lord Ramsay answered. “But you know how Eleanor is when she is determined.”

“Forbid her,” Hart said, words clipped.

Her father chuckled. “Forbid? Eleanor? The words do not belong in the same sentence.”

It hung there. Hart’s muscles tightened as he held on to the door frame. Eleanor remained ramrod straight, looking into the hazel eyes that were now red-rimmed and haggard.

He will never ask, she realized. Hart Mackenzie commands. He does not beg. He has no idea how to.

And there they always battled. Eleanor was not meek and obedient, and Hart meant to dominate every person in his path.

“Sparks,” Eleanor said.

Heat flared in Hart’s eyes. Hunger and anger.

They would have stood there all day, Hart and Eleanor facing each other, except that a large carriage rattled up to the front door. Franklin the footman, in his post outside, said something in greeting to the guest who stepped down from the carriage. Hart didn’t move.

He was still standing there, facing Eleanor in tableau, when his youngest brother, Ian Mackenzie, ran into the back of him.

Hart jerked around, and Ian stopped in impatience. “Hart, you are blocking the way.”

“Oh, hello, Ian,” Eleanor said around Hart. “How lovely to see you. Have you brought Beth with you?”

Ian prodded Hart’s shoulder with a large hand in a leather glove. “Move.”

Hart pushed away from the door frame. “Ian, what are you doing here? You’re supposed to be at Kilmorgan.”

Ian came all the way in, swept a gaze over Eleanor, ignored Hart, and focused his whiskey-colored eyes on a point between Eleanor and Lord Ramsay.

“Beth told me to send her love,” he said in his quick monotone. “You’ll see her at Cameron’s house when we go to Berkshire. Franklin, take the valises upstairs to my room.”

Eleanor could feel the fury rolling off Hart, but he would not shout at her with Ian standing between them.

Trust Ian to diffuse a situation, she thought. Ian might not understand what was going on, might not be able to sense the emotional strain of those around him, but he had an uncanny knack for controlling any room he walked into. He did it even better than Hart did.

Earl Ramsay was another who could diffuse tension. “So glad to see you, Ian. I’d be interested to hear what you have to say about some Ming dynasty pottery I’ve found. I’m a bit stuck on the markings—can’t make them out. I’m a botanist, a naturalist, and a historian, not a linguist.”

“You read thirteen languages, Father,” Eleanor said, never taking her gaze from Hart.

“Yes, but I’m more of a generalist. Never learned some of the specifics of the ancient languages, especially the Asian ones.”

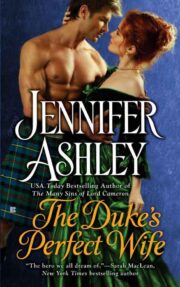

"The Duke’s Perfect Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.