CHAPTER 11

THE SCHOOL DAY PASSED in a muddy blur. The only class that was interesting enough to help me forget about what I wished I didn’t have to forget about was English. My teacher, Ms. Norton, was a spark plug filled with energy and information. She loved the shit out of books, which I couldn’t say for all of my English teachers. Some of them liked to analyze a book to death—suck all the truth and light out of a character until they were just inanimate, dissected letters on a page. We went over the year’s reading list, and I vaguely listened.

The only interaction I had with Leo that day was through the tiny glass window of the heavy metal hallway doors. We made eye contact, but I lost him in the shuffle of the passing period. Fine with me. Now that we’d actually talked, and then some, I didn’t even know what I wanted to say, or do, with him.

At lunch I checked my email in the library. Nothing new from Becca or her mom’s journal. I dug around online to see if I could learn anything specific about Becca’s treatment, but Google gave me billions of hits and I didn’t know what I was looking for anyway. According to Becca, treatments and drugs are tailored to each patient, so even if I did read something it might have nothing to do with what Becca was going through.

All my searching really did was make me puddle-on-the-floor depressed. Not only was my best friend going through this, but millions of other people’s best friends, moms, dads, sisters, brothers, fuck, even cats were going through it. I looked up at the ceiling and asked, “WHY?” I didn’t know who I was talking to. After my dad was killed, I pretty much gave up all belief in God. People loved to say “comforting” things to me, like, “It’s part of God’s plan” or “God only gives you what you can handle.” Um, fuck you? And fuck God. Seriously, if the god they believed in was giving out dead dads and cancer, I wanted nothing to do with him. And yeah, of course I can handle what was doled out to me. Because I was forced to. What were my options? Not handling it? Even that would be a choice and, therefore, the way I handled the situation.

It’s pretty damn hard to believe in God when you’ve lost so much. I know some people go the opposite way. God can be a great being to lean on, like a falling star to make all your superstitious wishes come true. But no matter how long or hard I prayed, I knew my dad would never come back. So why bother?

Still, as I stood up from my chair in the library, I mumbled, “Not her, too.” If there was a god, an all-seeing, all-hearing and -knowing superpower of a god, then he’d hear me and know what I was talking about. Not that he’d do anything about it.

After school, I drove to my job at Cellar Subs, a local institution loved by college students and the monetarily impaired. I was the only high school student who worked there, and I got the job after recommending Dead Alive to the owner. He went home and watched it the night of the interview, obviously wowed by my taste, and hired me the next day. The college students I worked with were a mix of art majors, lesbians, and frat boys. As much as I loved living here, what with the excellent public library system and the selection of old-timey movie theaters, I would never stay here to go to college. Or, at least, I wouldn’t have before my dad died. Now I couldn’t even think about college, about leaving. Mom needed me here, and I didn’t want to spend my year writing sob-story college applications. The new plan was to save up some money, maybe travel, and figure it out when I was ready. Becca’s cancer solidified my idea. Mom didn’t push. Maybe she wanted me around, too.

Being at work, where the college students always got to choose the music (that day was a totally weird band called Ween) and the business was always steady, turned out not to be so bad. The rhythmic slap of meat on bread put me at ease, so much so that it took several times of Leo calling, “Alex!” for me to recognize someone was talking to me. I wiped my meaty hands on the rag tucked into my shorts and old t-shirt, rotated from my sleep-shirt collection, and walked out of the kitchen. The restaurant was organized with the front counter at the bottom of the entrance stairway (because, naturally, the restaurant was in a cellar). Above the counter was a menu sloppily written in chalk. When people ordered they were given a number, and their handwritten ticket was passed back to me and my cohort, Doug, a kind of cute, definitely annoying sculpture major with a minor in astronomy. After one of us made the subs, usually me unless we were busy enough to warrant Doug to stop sketching and start sandwich making, we placed it in a basket, left the small, narrow kitchen behind the counter, and yelled out the customer’s number. Sometimes I liked to do it in an accent. Today, I just did it as loudly as I could.

Leo waited by the counter, ready to pick up an order.

“Hey,” I greeted him with confusion. “How did you know I worked here?”

“I didn’t. I always come here on Wednesdays after my tuba lesson.”

“You play the tuba?”

“No. I just thought it sounded funny.”

“So you’re stalking me?” I checked.

“Sorry, no. I actually come here after I pick up my comic subscriptions.”

“For real this time?”

“For real.”

“The tuba was cooler.”

“Says you.”

I ignored the annoyed looks of the college students around me, pretending I was oblivious to the fact that they wanted to eat.

“What number are you?” I nodded toward Leo’s order ticket.

“Forty-two.”

“The meaning of life, no less. I’ll be right back.”

I went into the kitchen and fixed Leo’s order, a veggie deluxe with cheddar and Muenster cheeses heated up. I popped the sub into the microwave above my head and prepared myself the Alex Special: turkey and Muenster, topped with a pile of pickles. When the microwave beeped, most definitely emitting heaps of radiation so near my brain, I informed Doug, “I’m taking my dinner. You have orders to make.” I didn’t wait around to see if he heard me, tossed my rag onto an empty counter, and carried out the two baskets to Leo.

“Lead the way,” he directed. I took him to my favorite spot next to a fake fireplace. Cellar Subs’ walls were covered in graffiti, one of those places that encourages it. I left my mark one night after closing, high on the wall so as not to be written over, standing on a ladder from the back room: “Belial was here,” a nod to the Basket Case Trilogy.

When we began eating, Leo said, “My compliments to the chef.”

“Mine, too,” I agreed. “So you really didn’t know I worked here?” I asked.

“Did you know I played basketball over at Irving?”

“Nope.”

“Then I didn’t know you worked here.”

“That kind of makes it sound like you did know I worked here, but that I was lying about knowing you played basketball at Irving. Which I wasn’t.”

“Pickles?” he questioned.

“Want one?” I offered.

“I’m good.”

We ate our subs, not breaking for more confusing chat until Leo, wiping his mouth on a tiny, useless napkin, asked, “Should I try a conversation starter?”

I liked the way Leo talked. It wasn’t as matter of fact as the way I spoke, but it wasn’t as forced as most people would be when getting to know someone. “Do you have one?” I asked.

“That was pretty much it.”

“And look at the conversation it started.” He shrugged. “I’ve got one,” I said. “My dad made it up. It’s called half and half. Like, half empty, half full. You’re supposed to say something that happened today that was half empty, you know, shitty? And then something half full, the good.” I waited for him to make fun of the quaintness, but he took a thoughtful pause and asked, “Can you go first? I need a minute to think.”

“Don’t think while I’m talking because then you’re not listening.”

“Thanks, Mom.”

I flipped him off pleasantly and said, “I’m getting drinks. You think about your half and half while I get us pop. What do you want?”

“Coke.”

I walked behind the counter to the drink fountain. Ila, a gorgeous women’s studies major with waist-length strawberry-blond hair, worked the register. “Who’s that?” She waggled her eyebrows at me. I could’ve been jealous at the thought of not only a college girl, but a beautiful one at that, ogling Leo, but Ila was a lesbian with the cutest girlfriend who, when not going to school full-time, worked as a carpenter.

“That’s Leo. From my school.”

“Is he your boyfriend?” she asked, completely ignoring the backup of customers. Part of the charm of Cellar.

“No. I don’t think so. I don’t know what he is. I barely know him, really.” I pumped the pop out of the fountain into two worn, plastic tumblers.

“But you want to know him, right?” Ila was overdoing the innuendo, but I liked the big-sisterly vibe.

“Yes. But I don’t know. We’ll see. Shit doesn’t seem to work out very well for me lately. Or ever.”

“Hopefully this isn’t shit then.” Ila started taking orders again, and I delivered our drinks.

“Thanks,” Leo said. “I thought of my halves, unless you want to go first.”

“After you.”

“My half empty is that my brother is still in Sangin, and my parents are constantly terrified. We don’t know when he’s coming home. And my mom has these screaming nightmares about it.”

“That is half empty. Are you close with your brother?”

“Yeah. I mean, he’s kind of the favorite in the family. My parents worship him. He’s annoyingly perfect. And I’m the family fuckup.”

“You don’t seem like such a fuckup.” I sipped my Coke through the straw.

“You must have heard some things.”

“Yeah, but not from you.”

“Probably everything you heard was true.”

“So you slept with Mrs. Johansen, the chorus teacher with the lazy eye?” I asked agape.

“No,” he blurted.

“You’ve been to jail?”

“No.”

“You have a tattoo on your ass that reads, ‘Kiss this’?”

“Are you kidding me? Who said that?”

“I just made that up. But that would’ve been awesome if you did.”

“Maybe you can give it to me.”

“What do you mean?” I smiled over the straw at the insinuation that I could give him a tattoo.

“Don’t you have a homemade one?”

“How did you know that?” I could barely contain the rush of Leo Dietz knowing a private factoid about me.

“I saw it once during gym class.”

The fact that Leo had watched my thigh at some point during gym class almost made me blush. “Anyway, so what rumors about you are true? Have you really been suspended?”

“I was suspended last year for busting out Daniel Lum’s teeth. Even though I didn’t really mean to do it. Whatever, the guy’s dad’s a dentist,” Leo mumbled.

“What else?” I pulsed the Coke through the straw in anticipation.

“I was also suspended for having a ‘weapon’”—he finger-quoted—“in my locker, which was bullshit because it was a pocketknife. Boy Scouts are allowed to have them.”

“Are you a Boy Scout?” I asked.

“What do you think?”

“How old are you?” I prodded. The rumor was that he was really twenty after being held back twice.

“Twenty-six,” he answered. I coughed on my Coke, until he said, “Really? You believed that?”

“What? I don’t know you. I mean, for all you know about me, I could be a serial killer.”

“I’m counting on it.” He smirked. Melt. “And I’m only seventeen.”

“So you weren’t held back?”

“I was, actually, after we moved. Behavior crap. But I had skipped kindergarten because I was so ahead of everyone. So it all balanced out.” We both nodded, and he said, “What about you?”

“I’m seventeen. No skipping or going back.”

“I meant your half empty.”

“Oh yeah.” I wasn’t sure what to say, if I wanted to get into Becca’s cancer. But he was honest with me, and I didn’t have to go into great detail. Not that I had many details. “My half empty is that my best friend has cancer. And she started treatment today, and I don’t know what’s going to happen or if she’ll live or die or when I get to see her or talk to her or if she’ll live or die and I know I just said that—” I nervously lifted my straw in and out of my cup, willing myself to hold it together.

“Jesus, Alex, I had no idea. That sucks. That’s like glass almost completely empty. Shit. I thought you were going to say something about your dad, but, damn. I don’t really know what to say. Sorry is such a loaded word.”

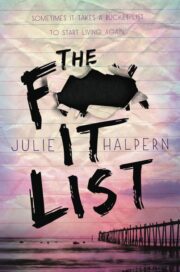

"The F- It List" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The F- It List". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The F- It List" друзьям в соцсетях.