‘They would farm the land out,’ I said. ‘They would forget to rest it. They would plant only vegetable crops for themselves. They would not have the capital to buy good seed-corn, to buy new animals for stock.’

‘Aye,’ said Ralph. ‘You’d have to put up the capital to make it work.’

‘Why should I?’ I demanded. ‘Why should anyone choose to chance their money for a scheme which might not even work?’

Ralph wheeled his horse around suddenly so that it blocked my path. He looked down on me from its high back and his face was very dark and very stern. ‘Because there are things which matter more than two per cent on Consols,’ he said. ‘Because you have been a privileged person in a country where there are people going hungry and you know there can be no peace for you. Because you know that to be one of the lucky ones when there is poverty all around is not to be lucky at all. It is to be miserable without even seeing your own misery. For it leaves you with a choice either to rejoice that you are doing well, when you know there are others who are doing badly, most badly, or to harden your heart. There are those who learn to harden their hearts so well that they can actually forget what has happened. They teach themselves to believe that they are rich through their own cleverness, or as a just reward for their virtues. They force themselves to think that the poor are thus because they are stupid, and deserve their poverty. And when that has happened, you have a country divided into two. And both sides are most ugly.’

I gasped. I could not keep up with Ralph. I had heard the complacency in the voices of the wealthy, I had heard the desperation in the voices of the poor. I wanted to belong to neither. ‘It would never work,’ I said uncertainly.

Ralph gave a little ‘Pfui!’ of disdain and turned his horse for home again. It was growing darker with the speed of a spring evening and the wood-pigeons were cooing lovingly, longingly. The rooks were flying late, crossing the grey sky with beakfuls of twigs. The blackbird sang as clear as a flute.

‘It would never work,’ I said again.

‘It’s not working now, is it?’ Ralph said lightly, as if the statement hardly merited an answer. ‘Thousands dying of want in the countryside, hundreds dying of dirt and drink and hunger in the towns. You can hardly call that “working,” can you?’

We came on to the drive while I was still puzzling for a reply, and minutes later we had reined in at the garden gate of the Dower House. Ralph would not come in but sat on his horse while Jem came out into the lane and helped me down.

‘You are not…angry, Mr Megson?’ I asked tentatively, watching the darkness of his face under his tricorne hat.

At once his face cleared and he smiled at me. ‘Lord love you for a fool, Julia Lacey,’ he said easily. ‘So full of your own importance that you think you are responsible for the Norman Conquest and for the abuse of the lords of the land ever since. Nay, I’m not angry, Miss Vanity. And if I was, it would not be with you.’ He paused and scrutinized me, his head on one side. ‘And furthermore, if I was, you would be quite able to tell me to keep my ill humour to myself, wouldn’t you?’

I hesitated at that. I had gone to Bath as a girl who was used to watching Richard’s face for the warning signs of his displeasure.

But I had come back a woman with confidence in herself and in her gifts. I looked at Ralph and I smiled at him and narrowed my eyes. ‘I think I could,’ I said.

‘You surely could,’ Ralph said, and grinned at me in his democratic, disrespectful fashion. Then he leaned down low and pulled me to his horse’s side, and before the parlour window of the Dower House he gave me a kiss on the cheeks as if I were a serving maid to be kissed in the lane. Then he straightened up, tipped his hat to me and trotted off down the drive.

I took one horror-struck survey of the Dower House windows, to check that Mama had indeed not seen, made one fearful scowling face at Jem to wipe the grin from his face at my discomfort, then I picked up the trailing hem of my riding habit and ran indoors with a ripple of laughter caught inside me at Ralph Megson’s impertinence.

I was so very busy that spring that if I had wanted to mope around, missing James, I would not have been able to do so. Uncle John and the Chichester lawyers had drawn up a set of contracts between the workers, the tenant farmers and the Wideacre estate. But I wanted to be there when they signed the contracts. It should be clear to them that I was giving my word as they were giving theirs. I spent many hours in the library with John, making sure that I understood the agreements we were making, the length of the individual leases, the proportion of the wages which were to be paid into the common fund, the time for repayment of loans for seed and equipment to tenant farmers and the interest we decided to charge. Often it was I who checked the lease through and exclaimed, ‘But, Uncle John! In addition to his debt to us, this tenant has to pay the poor rate and tithes. He has too costly a burden; we must make the debt run longer or he will not make enough to keep himself and a family in the first few years!’ Then John would recheck the figures and nod and say, ‘You are right, Julia. But it cuts back Wideacre profits.’

Uncle John and Ralph and I also had long planning sessions in the library with the maps of Wideacre spread before us. Ralph understood the land and could say what crops would grow and what would not take to the chalky Sussex earth. But John had read much about modern agricultural experiments and had lived on Wideacre during its prime and could speak about crops. I stayed quiet, but I kept my eyes and ears open, and I learned all I could during those friendly, easy talks.

Ralph and I were the ones out on the land, up on the downs checking the sheep, through the village checking for hardship as the cold weather grew damp and the frosts melted and became slushy and chill, riding around the lanes checking the hedges and the ditches. Sheep-proof and flood-proof, we wanted the land to be, and everything in readiness for the ploughing.

All the equipment had to be bought new. What had been left after the ruin of the Laceys after the last harvest had been sold or bartered for pitiful amounts of food during the years of Acre’s poverty. We had to buy new ploughs, new work-horses, new seed. A whole generation of young men had to be trained to drive a horse and follow a plough, for they had never seen it done by their fathers, and they had never been plough-boys themselves.

‘It can’t be done!’ John would sometimes say to me when I came home tired out from a day’s riding and with a list of things which had to be ready before the spring weather came and set the land in its cycle of growth. ‘It cannot be done this year!’

But, from somewhere, I had a great fund of confidence. I would smile at John not like a sixteen-year-old green girl but like someone far older and far wiser, and I would say, ‘It can be done, Uncle John. Mr Megson thinks so too, and I am sure it will be all right. Acre is working all the daylight hours to be ready in time for sowing. It can be done. And you, and I, and Mr Megson, and Acre are doing it.’

As if the planning and the preparation for sowing were not enough, the flock of sheep Uncle John had bought were not hardy and took against the lower fields that we thought would suit them. We lost two or three lambs, and even a ewe, which was more serious. After that Ralph said that, cost what it may, the animals would have to lamb under cover.

The barn they had used in autumn was too small for the whole flock, and it was too far for the shepherd to go every day. All the old barns had been pulled down years ago, the wood taken for firewood and the stones for building. So we had to have the flock in the Dower House stable block, with beams thrown across the yard and a loose thatch over the top. The smell was appalling and the noise they made! Mama said that she would never again read poems about the life of a shepherdess with any pleasure.

‘Hey Nonny No,’ John said at dinner, and grinned at her.

We were not like Quality, that spring.

‘We are pioneers,’ Mama said; and I loved her for understanding that working Wideacre in this way felt less like farming an estate in the heart of England and more like building a new country, a fresh country where one might forget the mistakes of the past and try to make something new and clean.

‘Squire Julia,’ Clary Dench called me ironically when I met her in Acre lane. She had taken her father’s dinner to him and was coming home with a jug and a plate under her arm. He had been working on the ditches and Clary too was speckled with the sandy mud.

‘You’d better curtsy,’ I said dourly. I looked little smarter than she did. I was wearing my cream riding habit, but it had lost its early style and was now creased and crumpled with a darn on the skirt where I had taken a tumble and ripped it. I was on foot, leading two plough-horses down to the village to be shod and for the plough-boys to practise driving a team. Clary and I both walked awkwardly, with the glutinous mud sticking to our boots. Her boots were older, the soles patched and re-patched. But when we were both muddy up to our eyebrows, one could tell little difference between the young lady of Quality and the village girl.

Clary laughed. ‘You look a sight!’ she said.

‘I know,’ I said ruefully. ‘I can hardly remember Bath now, and it’s not been that long.’

She nodded. ‘Remember the time when the village was bad?’ she asked. ‘It’s not an easy life now, no one could say it was. Bui at least we can see where we’re going. This spring is going to bring the sowing, and then there’ll be haymaking and harvest-time. There will be a proper harvest home. All the old parties and fair-days will come back. My ma and pa can’t talk of nothing else but the sowing and the maying.’

‘Maying!’ I said, stopping the horses with difficulty. People like to think of the great plough-horses as gentle giants, but I had led these two down from the Dower House stables and I could attest that they were hulking idiots without a listening ear between them, and without a brain in their heads.

‘Woah! you two,’ I said crossly. ‘What happens at the maying, Clary?’

‘It’s the Whitsun festival,’ she said, ‘when all the sowing is done and the early spring work is over. It’s a celebration of the spring. All the young men and women, all the lads and maids go up on to the downs before it is light, before dawn. They cut branches of the hawthorn tree and they dress them with ribbons, and they see the sunrise and welcome the spring in.’

‘Oh, yes,’ I said. It sounded rather tame. ‘Is that all, Clary?’

She gave me a sideways smiling glance. We had both grown up from the little girls who fought in the woods. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘it’s no accident that there’s a lot of marriages six months after that day. There’s a lot of courting that goes on while the sun is coming up, you know, Julia. And there are no elders there, and no one thinks the worse of anyone who slips away up on the downs. No one watches and no one counts, because it is the maying, you see.’

I smiled a little. ‘Oh,’ I said. I was a child compared to Clary, who had helped at childbirth and had wept already over a stillborn babe which would have been another sister for her. Clary and all the Acre children knew all about lust and birthing and dying, while Richard and I in the Dower House were naive beginners. But I had been in James’s arms, and felt his mouth on mine, and longed for his touch again. And I had Beatrice’s knowledge and Beatrice’s desires in my head. So I gave Clary a little smile and said, ‘Oh,’ which acknowledged that I was not squire, nor Miss Julia, but a maid like her with love to give and a longing to receive it.

‘Would you come out with us?’ she asked invitingly. ‘There’d be no harm. Many lasses just come out to watch the sunrise, and to cut the branches and take the spring home to their families.’

‘I should like that,’ I said.

‘I’ll tell ’em you’ll come out with us,’ said Clary. ‘Maybe they’ll make you the Queen of the May. And you tell your ma and your Uncle John that the village will take a week for the festival. At least some days.’

‘I will,’ I said. ‘But what happens?’

‘It’s the festival of misrule,’ Clary said. I turned the horses’ heads and she took one of the reins to help me lead them towards the forge. ‘Everyone dresses up in costume and there is a feast. The farmers with money give some when the band come around and demand a fee. The people who have no money give food for the feast. The Wideacre people go over to Havering, or to Singleton, or to Ambersham, and wherever they go, there is a party and dancing and free drink and free food. Then next year we have the other villages back to us. It’s been so long since Acre could dance that this year it is to be our turn.’

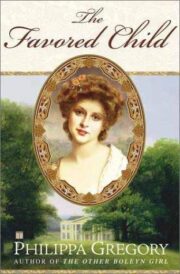

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.