‘Prostitutes?’ John’s voice was suddenly sharp. ‘Are you sure?’

‘I am merely telling you what Julia told me,’ Mama said with dignity. ‘I did not press her on it. Apparently one of the lost Acre children had become a prostitute – the one who refused to come home. She recognized him.’

‘This is a good deal more serious,’ John said. ‘I was thinking of perhaps an older married lady. I would be very anxious indeed if Julia’s betrothed used bagnios and suchlike.’

‘I fail to see the difference,’ Mama said impatiently. I heard her heels click on the polished floorboards. ‘It is still unchastity.’

John’s voice was warm, and I could tell he was smiling at her. ‘Morally, you are right, Celia,’ he said. ‘But speaking as a doctor.’ He paused. ‘There is a stew-pot of disease among the street women,’ he said. ‘Many of them are fatal, none of them curable. If James Fortescue has been with prostitutes, we should thank God that Julia learned of it in time.’

‘Oh,’ Mama said blankly.

‘You would not know,’ John said gently. ‘And I am content that neither you nor Julia will ever know how those women, and infected men, can suffer. But the diseases are easily caught and easily passed on. If James Fortescue habitually goes with such women, the engagement should certainly be ended.’

Mama was silent for a moment. ‘I shall take her away, then,’ she said, ‘for a few days. She shall come with me to Oxford when I visit Richard.’

Uncle John replied, but I had heard enough. I stole up the stairs in my stockinged feet and listened no more. I rang my bell and asked for water to be set on to boil for a bath. I felt utterly dirty. I could not dine with my beloved mama and my dear Uncle John until I had scrubbed myself all over.

‘So I am to lose you two gadabouts again, am I?’ Uncle John said in an injured tone later at dinner. ‘I can see that I have made a rod for my own back and Julia will be all around the country, leaving me to manage her beastly estate.’

The cheerfulness was a little forced, but I appreciated that neither of them wished to tax me further. I tried to smile, but I was fighting back another attack of sickness, with a large portion of Wideacre trout cooked in cream and wine sauce before me. The flesh was as pink as rose petals, the sauce shiny and yellow as butter with rich Wideacre milk. I could hardly bear to sit at the table with the smell of it, and I knew I could not eat it.

‘We shan’t be long in Oxford,’ Mama said when I did not answer. ‘And I should think you would be glad to have the house to yourself for a while. You will be able to dine in the library with your maps all around you, and no one will scold you for smoking cigars and going to bed late.’

‘Oh, yes,’ Uncle John said with relish. ‘I shall have a feast of forbidden luxuries. And when you come home, you will have to launder the curtains and scrub the carpets, the place will be so well seasoned with tobacco.’

I could hardly hear the two of them, and I could scarcely see my unwanted plate before me. The table seemed to be rising and falling like an undulating wave.

‘Mama, please excuse me,’ I whispered. ‘I do not feel well.’ I rose to my feet and took myself somehow out of the room and went to the parlour, and I sank down on the hearthrug before the flower-filled grate and tipped my head back against the chair.

I had lied to Mama this dinner-time, and I was going to have to go on lying. I had told her there was nothing wrong with me, and that was not true. There was something wrong with me and anyone but a fool would have guessed it weeks before.

I was with child.

My cousin Richard had got me with child, and I was ruined indeed.

I needed no threats or promises now to bind me to him. I was absolutely ruined unless he married me, and I knew full well that I must go to him and tell him that we must be married at once.

It had taken me weeks to understand the cause of my nausea and dizziness, and even then I had clung to the foolish hope that I was sick because my monthly bleeding was late. When it did not come, and did not come, I started to know. And when everything on Wideacre seemed alive and fruitful, I knew I was fertile also.

Twice I had started to write to Richard, and two pages of hot-pressed notepaper had ended up in the fire. I knew that we were betrothed in his eyes, and since the day he left for Oxford, when he had held me in a hard hurting grip and told me that no gentleman would ever want me now, I had known that there was no love for me in the future. No love, no marriage and no children.

I had faced that sentence. Faced it and thought that I could tolerate it. But now I had to face something worse. I did not want to be Richard’s wife. I could not bear the thought of a clandestine marriage which would shame Mama, and shame me; or a marriage with her reluctant consent because she knew I was ruined. But I could see no other way. I had spent weeks trying to pretend that the morning in the summer-house had never happened. But it had happened; and the bravest thing I had ever had to do was to look my shame in the face and say, ‘I should be better off dead than shamed in this way’, and know that I would not die. Instead I would have to marry, and marry fast, or run the risk of showing a belly on me which would be obvious enough in the new slim gowns, and my mama would be within her rights to have me turned from her door and never to see me again.

She would be disgraced by a clandestine match – but such a thing could be hushed up and forgotten within a few years. There would be an early baby, but Wideacre was a tolerant place where the old ways were still known. There were few weddings celebrated in the village church at which the bride did not have a broad belly to carry before her, and a flood of banns were read over the few weeks after the May courting on the downs. I would be clinging to my reputation by the skin of my teeth in the world of the Quality with a secret marriage and an early baby. But among the common people of Wideacre, I would be nothing out of the ordinary.

I straightened up and looked at the fire. I would never see James Fortescue ever again, and I flushed suddenly hot at the thought that somebody would be bound to tell him that pretty Julia Lacey, who was the toast of the season last year in Bath and had been quite his favourite for a while, had dashed into marriage not a moment too soon. He would be glad at the narrowness of his escape when he heard that. He might tell the gossip who whispered my name that he had wellnigh married me himself! And they would shake their heads and wonder that such a pleasant young lady should be such a whore. I put my face in my hands at that and sat without another idea in my head for a little while.

Then I shrugged.

I could not help it.

I had made a mistake, a grievous and awful mistake, and I would have to live with it and take the consequences.

It could have been worse, I tried to tell myself, seeking for some courage inside me and finding little. At least I loved my cousin Richard. I had wanted to marry him when we were children. He had held my heart in his hands since we were children together. I might close my eyes in the blankest of horror that we had to be married in such a disgraceful way, but at the end of the day I would have the two constant loves in my life: Richard and Wideacre.

Mama would be grieved. Mama would be distressed but.. .

I gave up the attempt to pretend that it would be all right. I could find no courage in myself, and I was too honest to pretend that a shameful secret marriage and an early baby was anything but a catastrophe in my life. But a pregnancy without being able to own the father would be immeasurably worse. There was no way that I could tell Mama that I was with child. There was no way that I could tell Uncle John. But if Richard would take my part and tell the lies we would need to tell, I might yet come through. Richard was the only person I could trust with the truth. Richard was the only person I could go to for help. There was only one way before me that I could see and that way led me directly to Richard at Oxford.

24

I hardly saw the town; the great grey colleges which fronted the streets looked more like prisons than palaces of learning to me. Mama was entranced by the style and the history of the place as we rattled to Richard’s college over the cobblestones; but I thought the windows too small and the façade of the buildings grim.

I learned later that the beauty of the colleges is hidden inside, that they are often built in a square with lovely secret gardens locked away. If the porter at the gate knows your name, you may walk inside the gateway and on through to a place of utter peace and silence where a cedar tree grows or where a fountain splashes.

From the outside they are forbidding, and all the secret gardens behind the walls did not compensate me for the way they seemed to frown at me as if they were all serious and thoughtful men and before them I was a silly girl who had lost her reputation and was growing big with a bastard child. Women were not welcome at Oxford, not even aunts and cousins, and pregnant mistresses would be utterly despised. It was a man’s place, and they kept their libraries, their books, their theatres and their gardens to themselves.

Richard was expecting us and had ordered tea for us in his lodgings, but he was quick to see the urgency in my eyes. I had forgotten his ability to deceive, and his start of surprise when he realized he had left some books at his tutor’s house would have convinced an all-seeing archangel. Mama agreed to sit down with a newspaper while Richard and I strolled down the road to fetch his books, and Richard turned to me as soon as we were clear of the house.

‘What is the matter?’ he said abruptly.

I noticed a certain grimness about his face and felt my heart sink. If Richard no longer wished to marry me, then I was lost indeed. ‘I had to see you . . .’ I started awkwardly. ‘Richard, it is about our being betrothed . . .’ My voice trailed off at the sudden darkening of his eyes.

‘What about it?’ he said, and I had to bite back a rush of panic because I had irritated him.

‘Richard,’ I said weakly. ‘Richard, you must help me, Richard, please!’

‘What do you want?’ he asked levelly.

We were walking down the road before the stone-faced men’s colleges as we talked, but at that I put both hands on his sleeve and tugged him to a standstill. ‘Richard,’ I said, ‘please don’t speak to me in that cold voice. I will be ruined unless you will save me. Richard! I am with child!’

He was delighted.

I know Richard. I could not mistake that blaze of blue in his eyes any more than I could mistake my own wan horror. I put my hands on his arm and told him I was ruined, and he was as delighted as if I had signed over Wideacre to him, and all of Sussex with it.

His eyelids dropped instantly to shield his expression. ‘Julia,’ he said gravely, ‘you are in very serious trouble.’

‘I know it!’ I said rapidly. But in some clear small corner of my mind I noted that he had said that it was I who was in trouble. He did not say we were.

‘It would kill your mama,’ he said. ‘She would have to send you away from home. You would not be able to stay at Wideacre. I think it would break her heart.’

I nodded. Anxiety had made my throat so tight that I could say nothing.

‘And you would be dropped entirely from society,’ Richard said. ‘None of your friends would ever see you again. It is a dreadful prospect. I cannot even think where you might live.’ He paused. ‘I suppose John might set you up in a little house abroad somewhere,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘or they might arrange a marriage for you with a tenant farmer or someone who would accept your shame.’

I tried to speak, but I could only make a sound like a little whimper. ‘Richard!’ I said imploringly.

‘Yes?’ he answered. He sounded distracted, as if he could ill spare the time for my interruption when he was trying to think what would become of me now that I was ruined.

‘We were betrothed,’ I said very softly. People walking past on the street turned to look at us, a handsome youth and a pretty girl holding tight to his arm and looking up into his face like a despairing beggar. Richard saw their glances and smoothly moved us on, tucking my cold hand under his elbow.

‘We were,’ he agreed, ‘but I thought you had been betrothed to someone else. The last word you gave me on the matter was that you wished to marry no one, that you wanted us to be brother and sister. I had the impression, Julia, I must say, that you were not enthusiastic about our marriage.’

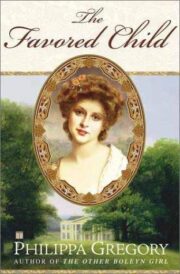

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.