The Duke said: “But how could I pay thirty thousand pounds?”

Mr. Shifnal caught the note of doubt in his voice, and congratulated himself on his wisdom in having left the young swell alone all day. He explained to the Duke how the sum could be found, and the Duke listened, and raised objections, and seemed first to agree, and then to think better of it. Mr. Shifnal thought that by the following morning he would know no hesitation, and was sorry that he had fortified him with meat and drink. He had been a little afraid that so delicate a young man might become seriously ill if starved, and a dead Duke was of no use to him. He determined not to allow him any breakfast, if he should still be obdurate in the morning, and he refused to leave the lantern behind him. Continued darkness and solitude, he was certain, would bring about a marked improvement in the Duke’s frame of mind. He went away again, warning the captive that it was of no use to shout, for no one would hear him if he did. The Duke was glad to know this, but he hunched a shoulder pettishly, and turned his face to the wall.

He forced himself to wait for what seemed an interminable time. When he judged that the hour must be somewhere near ten, he stood up, and felt in his pocket for the device he used to light his cigars. Under his finger the little flame sprang up obediently. He kindled one of the matches at it, and holding it carefully on high, located the position of the heap of lumber. He went over to it, and had picked up a splinter of wood before the match went out. He could feel that the wood was dry, and when he kindled a second match and held it to the splinter, it caught fire. The Duke found a longer splinter, and kindled that from the first, and stuck it into one of the bottles on the floor. The light it threw was not very good, and it several times had to be blown to renewed flame, but the Duke was able, in the glimmer, to find what be wanted, and to carry it over to the door. He built up there a careful pile of shavings of wood, scraps of old sacking, the broken chair, the broom, and anything else that looked as though it might burn easily. His tablets went to join the rest, the thin leaves being torn out, and crumpled, and poked under the wood. The Duke set fire to his heap, and thanked God that the cellar was not damp. He had to kneel down and blow the fitful flames, but his efforts were rewarded: the wood began to crackle; and the flames to leap higher. He got up, and observed his work with satisfaction. If the smoke rose to the upper floor, as he supposed it must, he could only hope that it would be drowned by the fumes of clay pipes in the tap-room. He collected his hat, and his cane, buttoned up his long drab coat, and added an old boot to his bonfire. It was becoming uncomfortably hot, and he was forced to stand back from it, watching anxiously to see whether the door would burn. In a short time he knew that it would. His heart began to beat so hard that he could almost hear it. He felt breathless, and the smoke was making his eyes smart. But the door was burning, and in a few minutes more the flames would be licking the walls on either side of it. The Duke caught up the horse-blanket, and, using it as a shield, attacked the flaming woodwork. He scorched himself in the process, but he succeeded in kicking away the centre of the door. He paid no heed to where the burning fragments fell, but he did smother the flames round the aperture he had made; and then, abandoning the charred blanket, swiftly dived for his hole, and struggled through it.

One moment he spent in recovering his breath, and settling his hat somewhat gingerly on his head, and then, taking a firm grip on his cane, he stole up the stairs.

He reached the top, and knew that he had been correct in his assumption that he wasimprisoned in the Bird in Hand. He remembered that there was a door leading into the yard at the back of the house, and he made for this. From the tap-room came the sound of convivial song and laughter. There was no one to be seen in the dimly lit space by the yard-door, and he thought for a moment that he was going to make his escape unperceived. And then, Just as he was within a few steps of his goal, a door on his right opened, and Mr. Mimms came out, carrying a large jug.

Mr. Mimms gave one startled grunt, dropped the jug, and lunged forward. The Duke was expert in the use of the singlestick, but he employed none of the arts he had been taught. Side-stepping Mr. Mimms’s bull-like rush, he made one neat thrust with his cane between his legs, and brought him crashing to the ground. The next instant he had reached the yard-door, and had torn it open, and was stumbling over the cobbles and the refuse outside the inn.

It was a dark night, and the yard seemed to be full of obstacles, but the Duke managed to get across it, to grope his way round a comer of the barn, and, as his eyes grew accustomed to the murk, to reach the field beyond. In the distance behind him, he thought he could hear voices. He thanked God that there was no moon, and ran for his life, heading in what he hoped was the direction of the village of Arlesey.

By the time he reached the straggling hedge that shut the fields off from the lane he was out of breath, and staggering on his feet. He was obliged to stand still, to recover himself a little, and he took the opportunity of looking back towards the inn. It was hidden from him by trees, but he was able to see a faint red glow, and realized that his fire must have taken good hold. He gave a panting laugh, and pushed his way through the hedge on to the lane. Mr. Mimms would have enough on his hands without adding the pursuit of his prisoner to it, he thought; and if the man in riding-dress thought the recapture of his prize of more importance than the quenching of the fire, the deep ditch beside the lane would afford excellent cover for a fugitive. The Duke walked as fast as he could down the lane, straining his ears for any sound of footsteps behind him. But he thought that he would be searched for in the fields rather than in the road.

The first cottages of Arlesey came into sight. Chinks of lamplight shone between several window-blinds. The Duke, reeling from mingled faintness and fatigue, chose a cottage at random, and knocked on the door. It was presently opened to him by a stolid-looking man in fustian breeches, and a velveret jacket, who opened his eyes at sight of his dishevelled visitor, and ejaculated: “Lord ha’ mussy! Whatever be the matter with you, sir?”

“Will you allow me to rest here till daylight?” said the Duke, leaning against the lintel of the door. “I have—suffered an accident, and—I rather fancy—some murderous fellows are on my heels.”

A stout woman, who had been peeping round her husband’s massive form, exclaimed: “The poor young gentleman! I’ll lay my life it’s them murdering thieves as haunts the Bird in Hand! Come you in, sir! come you in!”

“Thank you!” said the Duke, and fainted.

Chapter XVIII

The Duke left Arlesey on the following morning, unmolested, but slightly bedraggled. His hosts, upon his dramatic collapse, had carried him up to the second bedroom, and had not only stripped him of his outer garments, but had revived him with all manner of country remedies. They were very much shocked, Mrs. Shottery as much by the scorched state of his riding-coat as by his alarming pallor; and they perceived, by the fine quality of his linen, that he was of gentle birth. By the time that he had recovered his senses, the worthy couple had convinced each other that he had fallen a victim to the cut-throat thieves who infested the district, using the Bird in Hand as their headquarters. The Duke was feeling quite disinclined for conversation, and merely lay smiling wearily upon them, and murmuring his soft-toned thanks for their solicitude. Mrs. Shottery bustled about in high fettle, bringing up hot bricks to lay at his feet, strong possets to coax down his throat, and vinegar to soothe a possible headache, while her husband, having seen the glow of fire in the distance, sallied forth to reconnoitre. He came back just as the Duke was dropping asleep and told him with much headshaking, and many exclamations, that the Bird in Hand was ablaze, and such a to-do as he disremembered to have seen in Arlesey before.

In the morning, the Duke was touched to find that Mrs. Shottery had washed and ironed his shirt, and had even pressed out the creases in his olive-green coat. He said that he would not for the world have had her put herself to such trouble, but she would not listen to such foolishness, she said. Instead she showed him the scorch-marks on his drab riding-coat, mourning over the impossibility of eradicating them. Her husband eyed the Duke with respect, and said he reckoned he knew how the gentleman had come by the marks.

“What happened to the inn?” asked the Duke. “Is it quite burned down? Really, I never thought of that!”

“Well, it ain’t clean gone, but no one couldn’t live in it no more,” replied Mr. Shottery, with satisfaction. “And where that scoundrel Mimms has loped off to the lord alone knows! They say as he and the barman, and another cove went away in the cart, and so many bits and pieces piled up in it that it was a wonder the old nag could draw it. A good riddance to them all, is what I say!”

“If they don’t come back, which they likely will!” said his wife pessimistically.

“I think they will not,” said the Duke. “You may depend upon it that they are afraid that I shall lay information against them.”

“Which I trust and prays, sir, as you will!” said Mrs. Shottery, in minatory accents.

The Duke returned an evasive answer. He had certainly meant to do so, but a period of reflection had shown him the disadvantages of such proper action. His identity would have to be disclosed, and he was as little desirous of having it known that the Duke of Sale had been kidnapped as of advertising his presence in the district. He discovered, too, upon consideration, that having outwitted his enemies he felt himself to be quite in charity with them. His most pressing wish was to return to Hitchin, where his two protégés must by now be fancying themselves deserted.

He drove there in a gig, beside a shy man who had business in the town, and had agreed to carry the Duke along with him, The Shotterys bade him a fond farewell, and indignantly spurned his offer to pay them for his lodging. He said, colouring like a boy, that he thought he had given them a great deal of trouble, but they assured him that they grudged nothing to anyone who could smoke out a nest of thieves, as he had done.

The day was fine, and a night’s repose had restored the Duke to the enjoyment of his usual health. He was inclined to feel pleased with himself, and to think that for a greenhorn he had acquitted himself creditably. It seemed unlikely that Liversedge and his associates would dare to make any further attempt upon his life, or his liberty, and it was reasonable to suppose that he had come to an end of his adventures. Nothing now remained but to convey Tom and Belinda to Bath, and to hand Belinda over to Harriet while he himself searched for Mr. Mudgley.

He reckoned without his hosts. When the gig set him down at the Sun Inn, and he walked into this hostelry, he was met by popping eyes and gaping mouths, and informed by the landlord that no one had expected to see him again. The Duke raised his brows at this, for he did not relish the landlord’s tone, and said: “How is this? Since I have not paid my shot you must have been sure of my return.”

It was plain that the landlord had had no such certainty. He said feebly: “I’m downright glad to see your honour back, but the way things have been ever since you went off, sir, I wouldn’t be surprised at nothing, and that’s the truth!”

The Duke was conscious of a sinking at the pit of his stomach. “Has anything gone amiss?” he asked.

“Oh, no!” said the landlord sarcastically, his wrongs rising forcibly to his mind. “Oh, no, sir! I’ve only had the constables here, and my good name blown upon, for to have the constables nosing round an inn is enough to ruin it, and this posting-house which has given beds to the gentry and the nobility too, and never a breath of scandal the years I’ve owned it!”

The Duke now perceived that he had not yet come to the end of his adventures. He sighed, and said: “Well I suppose it is Master Tom! What mischief has he been engaged upon while I was away?”

The landlord’s bosom swelled. “If it’s your notion of mischief, sir, to be took up for a dangerous rogue, it ain’t mine! Robbery on the King’s highroad, that’s what the charge is! Firing at honest citizens—old Mr. Stalybridge, too, as is highly respected in the town! Hell be transported, if he ain’t hanged, and a good thing too, that’s what I say!”

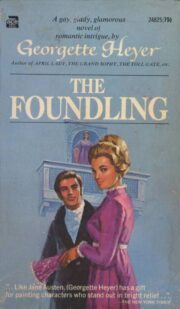

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.