“Good,” murmured Augustus.

Not precisely good from an escape point of view, considered Emma, but very, very good in every other way. Georges hadn’t stinted on his carriage. It might have been built for speed, but it was nicely padded, with a wider than average bench. Naturally. Ordinarily, Emma might have rolled her eyes at that. But Emma was too busy rolling other things to worry about Georges and his morals. She was feeling rather delightfully immoral at the moment.

“They warned me about poets,” she whispered, kissing the side of his neck. “Out for just one thing.”

“Inspiration?” Augustus suggested, touched the side of her cheek in a way that made her feel like every Venus ever painted or carved.

She cradled his hand, mirroring the curve of it with hers, putting everything she felt into her touch and her lips as he eased her slowly back against Georges’ extravagantly padded cushions.

“What?” Emma scooted sideways, breaking the kiss as something collapsed noisily beneath her back.

Augustus levered himself upright, his breathing labored. “Not. Again.”

“Yes, again.” It would have been amusing if it hadn’t been quite so annoying. Emma removed the slightly squashed roll of plans from beneath her back. “These plans are alarmingly ubiquitous.”

“For you,” said Augustus wryly. “Others search for them. You sit on them.”

Had that only been last night? It felt as though a lifetime had passed since she had last sat on these plans. Like Shakespeare’s great reckoning in a little room, it took only a tiny speck of time for everything to change around one. She wondered, now, how she hadn’t known before.

“What did you resolve with Mr. Fulton?” she asked. “Is he to follow?”

Augustus settled back against the seat. “Fulton will pretend to be properly indignant. Then he’ll join us in London en route to New York.”

Us. He said it so unself-consciously. She hadn’t been part of an us for a very long time. “Are we to settle in London, then?” she asked tentatively.

He didn’t answer directly. Instead, he looked at her from under the brim of Georges’ hat. “Will you miss your house?”

She didn’t ask which one. He had never seen Carmagnac. She knew the one he meant, the one in town, the one where they had spent hours together in her book room. It wasn’t just her house he was asking about, she knew; he meant her cook, who prepared those tea cakes he liked so much, and the footmen who opened the door to him, and her own personalized sedan chair, and all the rounds of parties and friends that had been so much a part of her life in Paris. She had only, she realized, the clothes on her back, and those were now rumpled and stained. They would be even worse by the time they reached London.

She had the clothes on her back and some paste jewelry. She went to a place where she knew no one, a place where she would have to learn everything except the language, and even that had its own divergences from the one she knew.

Back in Paris, there was a town house decorated to her specifications; a wardrobe full of clothes they couldn’t afford to replace; a whole world, a life. Emma looked at Augustus, and down at his hand, where it held hers. No, she thought. She regretted none of it.

With the exception of one thing.

“I never said good-bye to Hortense,” she said.

Augustus’s hand tightened briefly on hers, in an almost convulsive gesture. When he spoke, his voice was so low that Emma had to strain to hear him. “You can still go back.”

“What?” said Emma.

“If you wanted to.” Augustus’s face was earnest in the shadows. He tried to draw his hand away, but Emma held on to it and wouldn’t let him go. “You could tell them that I kidnapped you, that I took you along as a bargaining chip in case of capture. They’ll believe you.”

“You’re willing to give me up?” said Emma, half laughing. “As easily as that?”

“Don’t think it’s easy,” he said quietly.

The smile died on Emma’s face. He meant it. If she asked him, he would let her out of the carriage, drop her off wherever it was that she asked, let her go back to her old life without him. Fair enough. On the face of it, what she was doing was absurd. Another elopement, this time with treason, in the middle of the night, with a man who had repeatedly lied to her.

It might be wrong, but it felt entirely right.

“You’re being noble,” she said. “Don’t be.”

“I don’t want to take your choices away from you,” he said. “Just because I pushed you into the carriage—”

“It was more of a pull, really,” said Emma absently. “With a bit of a yank.”

Augustus wasn’t smiling. “I’m serious.”

Emma lifted her eyes to his. “So am I. I made my choice. I made it long before you pulled me into this carriage. Well, several minutes before, at least. As soon as I heard de Lilly trying to get to the Emperor, I knew.”

“What did you know?” he asked quietly.

Emma pleated the folds of her dress between her fingers. Nervous hands, she could hear her mother say. Smoothing the fabric down over her thighs, she raised her eyes and said, “That some things are worth the risk.”

Outside, the countryside rattled past, but inside, all was still, the world reduced to Augustus’s eyes on hers. “Such as?”

Emma looked away. “I’ve always wanted a floral kirtle, embroidered all with leaves of myrtle. I’ll start a fashion for it.”

“Flowers wither,” Augustus reminded her. His hand found hers in the darkness, his thumb stroking up along the side of her hand towards her palm.

“Your masterful way with alliteration, then,” she said. “Your knee-weakening rhymes.”

“I thought they were stomach weakening,” he said. His finger moved in small circles in her palm, concentrating all sensation, all thought, on that one small motion.

Emma cast around for nonsense and couldn’t find it. Her arsenal of frivolity had deserted her, as surely as her jewels. She felt bare and exposed. Flowers withered; words lied.

“You make me feel like I’m special,” she blurted out. It sounded very silly, but Emma couldn’t think of any other way to put it. “You make me feel like I matter.”

Augustus lifted her hand to his lips. It was one of Georges’ favorite gestures, the kiss to the palm, but when Augustus did it, it felt different. It felt like he meant it. “You do matter. You matter to a lot of people.”

It was clearly meant to be a compliment, but Emma found herself feeling oddly disappointed. Yes, it was nice to matter to a lot of people, but she wanted to matter to him.

Augustus pressed his lips to her curled fingers. “You matter to your old school friends.” Another kiss. “You matter to your cousin.” He paused, brooding over her fingers, before adding, “You mattered to Delagardie.”

“Paul?” She felt Augustus stiffen a little at the name. If she had to get used to there having been a Jane, he would have to get used to there having been a Paul. “I never mattered as much to Paul as Carmagnac. As for Hortense and the others, they love me, but they don’t need me.”

She looked at him, asking a question she couldn’t make herself ask.

“You matter to me,” he said quietly. “Do I matter to you?”

What fools they both were, Emma thought. Here they had just written reams of extravagant poetry together, in which they had lightly tossed about such terms as “passion,” “devotion,” and yes, “love.” But when it came to their own hearts, they were like children, robbed of all their sophisticated vocabulary and grand ideas.

“I love you,” she said. “Will that do?”

His fingers twined in hers, holding her fast. “Only,” he said, “if you give me leave to spend the next fifty years showing you how much I love you.”

“Showing?” said Emma, a whisper away from his lips. “Not telling?”

Augustus raised his brows. “Do you really want me to write you poetry?”

Chapter 34

Sussex, England

May 2004

“He’s really not half bad,” I said, without turning around.

I was standing on the veranda at the back of Selwick Hall, leaning against the stone balustrade that overlooked the gardens. Below, Micah Stone, looking rather dashing in knee breeches as a Regency era Benedick, was informing the camera that one woman was fair, yet he was well, and another wise and so on. He didn’t pretend to an English accent he didn’t have, and the overall effect was surprisingly mellifluous. He had one of those rubbery, flexible faces, nondescript in repose, expressive in role.

“Shouldn’t you be working?” said Colin.

His sleeve brushed my bare arm as he leaned against the balustrade next to me. It was one of those unseasonably warm May days, one of those days when England tried to make up for the previous nine months in a blaze of sunshine and a riot of spring flowers. In short, it was very heaven and I was definitely going to get a sunburn.

“I hit a breaking point,” I said. “Did you know that Napoleon commissioned a submarine to blow up the Channel fleet? He uncommissioned it because he claimed it leaked.”

There was also the small matter of Augustus Whittlesby running off with the plans and Bonaparte’s stepdaughter’s best friend. I’d been curious enough to look up Whittlesby in the Dictionary of National Biography. He had a whole two paragraphs, not bad for the DNB. Not one of them mentioned him as either a poet or a spy. Instead, he was known as a progressive member of Parliament—some faction of Whig, which had splintered into more factions than members—and the editor of a journal called The New Spectator, a direct challenge, one presumed, to the old Spectator.

He had a wife called Emma.

Women seldom fare well in printed history. It’s only the murderesses and adventuresses who achieve recognition in their own right. Otherwise, they seem to be remembered primarily in relation to the men in their lives, and Emma was no exception. Augustus Whittlesby was married to Emma Morris Delagardie, niece to the American president James Monroe. Of the rest of it, nothing. There was nothing to indicate what her life would have been once she followed Augustus to England.

Was she happy? I wondered. Did she regret the loss of her old school friends in France? Was she lonely without them, without the world she had built up around herself?

It wasn’t Emma Delagardie Whittlesby I was worried about, I realized. It was me. I wasn’t asking so much whether Emma had fit in, but whether I would. It made sense, I supposed. Two New Yorkers, two Englishmen, two centuries apart. The parallels were hard to ignore, especially with the question so very much on my mind: Would I be a fool to stay in England? Or would I be an even worse fool to go?

There was a major difference between me and Emma Delagardie. France was an adopted country for her, a transitory place, changing all around her. She had already left her family and home far behind. Whereas for me…

Well, maybe Cambridge was, too. Our first day of grad school, the head of the department had given us a speech, of which the most memorable—and most repeated—line was “Cambridge is a lovely place to live. It is also a lovely place to leave.” Translation: They wanted us to finish our degrees and get out, not hang around forever.

Like Emma in Paris, my Cambridge was transitory. Liz, Jenny, the whole fellowship I had built up around myself, would also depart, taking jobs in far-flung history departments across the country. Would UCLA really feel closer to home than London? California was the same six hours from the East Coast and just as culturally divorced.

Colin and I hadn’t discussed it, not since Jeremy had dropped his bombshell. There’s nothing like the rumor of buried treasure to effectively change the topic.

Jeremy swore that the Pink Carnation had somehow run off with the missing treasure of the Rajah of Berar, lost during the third Mahratta War in 1803, and hidden it in Selwick Hall. I could have told him that the Pink Carnation had never been in India, or in Berar, at least not according to my research, but Jeremy wasn’t interested in fact when legend was far more enticing. What with confronting Jeremy, herding everyone else into dinner, and apologizing to Micah Stone, there hadn’t been much time to talk about our future.

And since then…Well, let’s just say that both Colin and I are very good at avoiding things. Neither of us are what you would call “let’s talk about our feelings” types, which means lots of time spent talking around things and playing with subtext. Clever, but not precisely healthy.

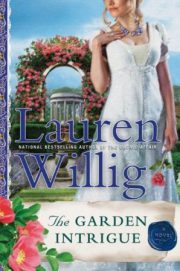

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.