Having made up her mind to intervene in Hubert’s affairs, it was characteristic of her that she wasted no time in further heartburnings. It was also characteristic of her that she made no attempt to persuade herself that she might with propriety draw upon Sir Horace’s funds to defray Hubert’s debt. In her view, which he would undoubtedly have shared, it was one thing to spend five hundred pounds on a ball to launch herself into London society and quite another to force him into an act of generosity toward a nephew of whose very existence he was in all probability oblivious. Instead, she unlocked her jewel case, and, after turning over its contents, abstracted from it the diamond earrings Sir Horace had bought for her at Rundell and Bridge only a year earlier. They were singularly fine stones, and it cost her a slight pang to part with them, but the rest of her more valuable jewelry had been left to her by her mother, and although she had not the smallest recollection of this lady, her scruples forbade her to part with her trinkets.

Upon the following day, she contrived to excuse herself from accompanying Lady Ombersley and Cecilia to a silk warehouse in the Strand, and instead sallied forth quite unaccompanied to those noted jewelers, Rundell and Bridge. The shop was empty of customers when she arrived, but the sight of a young lady of commanding height and presence, and dressed, moreover, in the first style of elegance, brought the head salesman hurrying forward, all eagerness to oblige. He was an excellent man of business, who prided himself on never forgetting the face of a valued customer.

He recognized Miss Stanton-Lacy at a glance, set a chair for her with his own august hands, and begged to be told what he might have the honor of showing her. When he discovered the true nature of her business he looked thunderstruck, but swiftly concealed his amazement, and, by a flicker of the eyelids, conveyed to an intelligent underling an order to summon on to the scene Mr. Bridge himself. Mr. Bridge, gliding into the shop and bowing politely to the daughter of a patron who had bought many expensive trinkets of him (though mostly for quite a different class of female), begged Sophy to go with him into his private office at the back of the showroom. Whatever he may have thought of her wish to dispose of earrings carefully chosen by herself only a year before he kept to himself.

A civil inquiry for Sir Horace having elicited the information that he was at present in Brazil, Mr. Bridge, putting two and two together, instantly resolved to buy the earrings back at a handsome figure, instead of resorting, as had been his first intention, to the time-honored custom of explaining to his client just why the price of diamonds had fallen so low. He had no intention of selling the earrings again; he would put them by until the return of Sir Horace from Brazil. Sir Horace, he shrewdly suspected, would repurchase them; and his gratification at being able to do so reasonably would no doubt find expression, in the future, in buying a great many more expensive trifles from the jewelers who had behaved in so gentlemanly a way toward his only daughter. The transaction, therefore, between Miss Stanton-Lacy and Mr. Bridge was conducted on the most genteel lines possible, each party being perfectly satisfied with the bargain. Mr. Bridge, the soul of discretion, kept Miss Stanton-Lacy in his private office until two other customers had left the shop. He fancied that Sir Horace might not wish it to be known that his daughter had been reduced to selling her jewelry. Without a blink he agreed to pay Sophy five hundred pounds in bills; without a blink he counted them out on the table before her; and without the least diminution in respect did he presently bow her out of the shop.

The bills stuffed into her muff, Sophy next hailed a hackney and desired the coachman to drive her to Bear Alley. The vehicle she selected was by no means the first or the smartest which lumbered past her, but it was driven by the most prepossessing jarvey. He was a burly, middle-aged man, with a rubicund and jovial countenance, in whom Sophy felt that she might repose a certain degree of confidence, this belief being strengthened by the manner in which he received her order. After eyeing her shrewdly and stroking his chin with one mittened hand, he gave it as his opinion that she had mistaken the direction, Bear Alley not being, to his way of thinking, the sort of locality to which a lady of her quality would wish to be taken.

“No, is it a back slum?” asked Sophy.

“It ain’t the place for a young lady,” repeated the jarvey, declining to commit himself on this point. He added that he had daughters of his own, begging her pardon.

“Well, back slum or not, that is where I wish to go,” said Sophy. “I have business with a Mr. Goldhanger there, who, I daresay, is a great rogue; and you look to me just the sort of man I may trust not to drive off and leave me there.”

She then got up into the hackney; the jarvey shut the door upon her, climbed back on to the box, and, after expressing to the ambient air his desire to be floored if ever he should be so betwattled again, besought his horse to get up.

Bear Alley, which led eastward from the Fleet Market, was a narrow and malodorous lane, where filth of every description lay moldering between the uneven cobbles. The shadow of the great prison seemed to brood over the whole district, and even the people who trod the streets or lounged on doorsteps, had a depressed look not entirely attributable to their circumstances. The coachman inquired of a man in a greasy muffler whether he knew Mr. Goldhanger’s abode, and was directed to a house halfway up the alley, his informant hesitating palpably before answering and seeming disinclined to enter into any sort of conversation.

A dingy hackney, once a gentleman’s coach, attracted little notice, but when it drew up and a tall, well-dressed young woman alighted, holding up her flounced skirts to avoid soiling them against a pile of garbage, several loafers and two small, ragged boys drew near to stare at her. Various comments were made, but these were happily phrased in such cant terms as were quite incomprehensible to Sophy. She had been stared out of countenance in too many Spanish and Portuguese villages to be in any way discomposed by the attention she was attracting, and after running a critical eye over her audience, beckoned to one of the small boys, and said with a smile, “Tell me, does a man called Goldhanger live here?”

The urchin gaped at her, but when she held out a shilling to him, caught his breath sharply, and, stretching out a claw of a hand, uttered; “Fust floor!” He then grabbed the coin and took to his heels before any of his seniors could relieve him of it.

The glimpse of largesse made the crowd converge on Sophy, but the jarvey climbed down from the box, his whip in his hand, and genially invited anyone who had a fancy for a little of the home-brewed to come on. No one accepted the invitation, and Sophy said, “Thank you, but pray do not start a brawl! I wish you will wait for me here, if you please.”

“If I was you, missie,” said the jarvey earnestly, “I’d keep out of a ken like this here, that’s what I’d do! You don’t know what might happen to you!”

“Well, if anything happens to me,” responded Sophy cheerfully, “I shall give a loud scream, and you may come in and rescue me. I shall not, I think, keep you waiting for very long.”

She then picked her way through the kennel and entered the house that had been pointed out to her. The door stood open and a flight of uncarpeted stairs lay at the end of a short passage. She went up them and found herself on a small landing. Two doors gave on to this, so she knocked on them both in an imperative way. There was a pause, and she had an unpleasant feeling that she was being watched. She looked around, but there was no one in sight, and it was only when she turned her head again that she saw that an unmistakable eye was regarding her though a small hole in one of the panels of the door at the back of the house. It disappeared instantly; there was the sound of a key turning in a lock, and the door was slowly opened to reveal a thin, swarthy individual, with long greasy curls and Semitic nose, and an ingratiating leer. He was dressed in a suit of rusty black, and nothing about him suggested sufficient affluence to lend as much as five hundred pence to anyone. His hooded eyes rapidly took in every detail of Sophy’s appearance, from the curled feathers in her high-crowned hat to the neat kid boots upon her feet.

“Good morning!” said Sophy. “Are you Mr. Goldhanger?”

He stood, a little bent, before her, wiping his hands together. “And what would you be wanting with Mr. Goldhanger, my lady?” he asked.

“I have business with him,” replied Sophy. “So if you are he please do not keep me standing in this dirty passage any longer! I cannot conceive why you do not at least sweep the floors!”

Mr. Goldhanger was considerably taken aback, a thing that had not happened to him for a very long time. He was accustomed to receiving all sorts and conditions of visitors, from furtive persons who stole into the house under cover of darkness and spilled strange wares upon the desk under the light of the one oil lamp, to haggard-eyed young men of fashion seeking relief from their immediate obligations, but never before had he opened his door to a self-possessed young lady who took him to task for not sweeping the floors.

“I wish you will stop staring at me in that foolish way!” said Sophy. “You have already peered at me through that hole in the door, and you must by now have convinced yourself that I am not a law officer in disguise.”

Mr. Goldhanger protested. The insinuation that he would not welcome a visit from a law officer seemed to wound him. However, he stood back to allow Sophy to enter the room and invited her to take a chair on one side of the large desk which occupied the center of the floor.

“Yes, but I shall be obliged to you if you will first dust it,” she said.

Mr. Goldhanger performed this office with one of his long coattails. He heard the key grate behind him, and turned sharply to see his visitor removing it from the lock.

“You won’t object to my locking the door, I daresay,” said Sophy. “I don’t in the least desire to be interrupted by any of your acquaintances, you see. And since I should much dislike to be spied on, you will permit me to stuff my handkerchief into that Judas of yours.” She removed one hand from her large swansdown muff as she spoke and poked a corner of her handkerchief into the hole.

Mr. Goldhanger had the oddest feeling that the world had begun to revolve in reverse. For years he had taken care never to get into any situation he was unable to command, and his visitors were more in the habit of pleading with him than of locking the door and ordering him to dust the furniture. He could see no particular harm in allowing Sophy to retain the key, for although she was a large young woman he had no doubt of being able to wrest it from her should such a need arise. His instinct made him prefer, whenever possible, to maintain a manner of the utmost urbanity, so he now smiled and bowed, and said that my lady was welcome to do what she pleased in his humble abode. He then betook himself to the chair on the other side of the desk and asked what he might have the honor of doing for her.

“I have come on a very simple matter,” responded Sophy. “It is merely to recover from you Mr. Hubert Rivenhall’s bond and the emerald ring given you as a pledge.”

“That,” said Mr. Goldhanger, smiling more ingratiatingly than ever, “is indeed a simple matter. I shall be delighted to oblige you, my lady. I need not ask whether you have brought with you the funds, for I am sure such a businesslike lady — ”

“Now, that is excellent!” interrupted Sophy cordially. “I find that so many persons imagine that if one is a female one has no head for business, and that, of course, leads to a sad waste of time. I must tell you at once that when you lent five hundred pounds to Mr. Rivenhall you lent money to a minor. I expect I need not explain to you what that means.”

She smiled in the most friendly way as she spoke these words, and Mr. Goldhanger smiled back at her, and said softly, “What a well-informed young lady, to be sure! If I sued Mr. Rivenhall for my money I could not recover it. But I do not think Mr. Rivenhall would like me to sue him for it.”

“Of course he would not,” Sophy agreed. “Moreover, although it was extremely wrong of you to have lent him any money, it seems unjust that you should not at least recover the principal.”

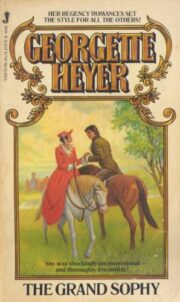

"The Grand Sophy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Grand Sophy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Grand Sophy" друзьям в соцсетях.