He was white with anger, an anger that had very little to do with her slighting reference to his ability to handle a pistol, but even as he leveled the gun, he seemed in some measure to recollect himself, for he lowered his arm again, and said, “I cannot! Not with a pistol I don’t know!”

“Faintheart!” mocked Sophy.

He cast her a glance of dislike, stepped forward to twitch the card out of her hand, and stuck it against the wall under the corner of a picture. In great interest, Sophy watched him walk away to the other end of the room, turn, jerk up his arm, and fire. An explosion, deafening in the confined space of the room, shattered the stillness, and the bullet, nicking one edge of the card, buried itself in the wall.

“I told you that it threw left,” Sophy reminded him, critically surveying his handiwork. “Shall we reload it so that I may show you what I can do?”

They looked at one another. The enormity of his conduct suddenly dawned on Mr. Rivenhall, and he began to laugh. “Sophy, you — you devil!”

That made Sophy laugh too, so when a startled crowd of persons burst into the room a minute or two later, they found only a scene of unbridled mirth. Lady Ombersley, Cecilia, Miss Wraxton, Lord Bromford, Hubert, one of the footmen, and two housemaids all clustered in the doorway, evidently in the expectation of beholding the results of a shocking accident.

“I could murder you, Sophy!” said Mr. Rivenhall.

“Unjust! Did I tell you to do it?” she countered. “Dear Aunt Lizzie, do not look so alarmed! Charles was — was merely satisfying himself that my pistol was in order!”

By this time the eyes of most of the company had discovered the rent in the wall. Lady Ombersley, clutching Hubert’s arm for support, faintly enunciated, “Are you mad, Charles?”

He looked a little guiltily at the havoc he had wrought. “I must be, I suppose. The damage can soon be made good, however. It does throw left, Sophy. I would give much to see you fire it! What a pity I cannot take you to Manton’s!”

“Is that Sophy’s pistol?” asked Hubert, much interested. “By Jupiter, you are an out-and-outer, Sophy! But what possessed you to fire it here, Charles? You must be mad!”

“It was, naturally, an accident,” pronounced Lord Bromford. “A man in his senses, which we cannot doubt Rivenhall to be, does not, of intent, fire a pistol in the presence of ladies. My dear Miss Stanton-Lacy, you have sustained a severe shock to the nerves! It could not be otherwise. Let me beg you to repose yourself for a while!”

“I am not such a poor creature!” Sophy replied, her eyes still brimming with laughter. “Charles will bear me out, if there is any truth in him, that I neither squeaked nor jumped! Sir Horace nipped such bad habits in the bud by soundly boxing my ears!”

“I am sure you are always an example to us all!” said Miss Wraxton acidly. “One can only envy you your iron composure! I, alas, am made of weaker stuff and must confess to have been very much startled by such an unprecedented noise in this house. I do not know what you can have been about, Charles. Or is it indeed Miss Stanton-Lacy’s pistol, and was she exhibiting her skill to you?”

“On the contrary! It was I who shot disgracefully wide of my mark. May I clean this for you, Sophy?”

She shook her head and held out her hand for the gun. “Thank you, but I like to clean and load it myself.”

“Load it?” gasped Lady Ombersley. “Sophy, you do not mean to load that horrid thing again, surely?”

Hubert laughed. “I said she was a redoubtable girl, Charles! I say, Sophy, do you always keep it loaded?”

“Yes, for how can one tell when one may need it, and what is the use of an empty pistol? You know what a delicate business it is, too! I daresay Charles can do it in a trice, but I cannot!”

He gave the gun into her hand. “If we go down to Ombersley this summer, we much have a match, you and I,” he said. As their hands met, and she took the gun, his grasped her wrist and held it for a moment. “An infamous thing to have done,” he said, in a slightly lowered tone. “I beg your pardon — and I thank you!”

Chapter 13

IT WAS not to be supposed that this incident would be pleasing to Miss Wraxton. A degree of understanding seemed to be existent between Mr. Rivenhall and his cousin which was not at all to her taste, for although she was not in love with him, and indeed, would have considered such an emotion very far beneath her station, she had made up her mind to marry him and was feminine enough to resent his paying the least attention to any other female.

Fortune had not smiled upon Miss Wraxton. She had been contracted, in schoolroom days, to a nobleman of impeccable lineage and respectable fortune, who had been carried off by an attack of smallpox before she was of an age to be formally affianced to him. Several eligible gentlemen had shown faint tendencies to dangle after her during her first two seasons upon the Marriage Mart, for she was a handsome girl with a handsome portion; but for unaccountable reasons none of them had come up to scratch, as her elder brother, Lord Orsett, rather vulgarly phrased it. Mr. Rivenhall’s offer had been made at a moment when she had begun to fear that she might be left upon the shelf, and had been thankfully received. Miss Wraxton, reared in the strictest propriety, had never taken any undesirably romantic notions into her head and had had no hesitation in informing her papa that she was willing to receive Mr. Rivenhall’s addresses. Lord Brinklow, who held Lord Ombersley in the greatest aversion, would certainly not have entertained Mr. Rivenhall’s offer for as much as a minute had it not been for the providential death of Matthew Rivenhall. But the old nabob’s fortune was something not to be despised even by the most sanctimonious of peers. Lord Brinklow had informed his daughter that Charles Rivenhall’s suit carried his blessing with it; and Lady Brinklow, a sterner moralist even than her spouse, had clearly indicated to Eugenia where her duty lay and by what means she might hope to detach Charles from his unregenerate family.

An apt pupil, Miss Wraxton had thereafter lost no opportunity of pointing out to Charles, in the most tactful way, the delinquencies and general undesirability of his father and his brothers and sisters. She was actuated by the purest of motives; she considered that the volatility of Lord Ombersley and Hubert was prejudicial to Charles’s interests; she heartily despised Lady Ombersley and as heartily deprecated the excessive sentiment which made Cecilia contemplate marriage with a penniless younger son. It seemed to her that to detach Charles from his family must be her first object, but sometimes she was seduced into playing with the notion of reclaiming the Ombersley household from the abyss of impropriety into which it had fallen.

Becoming engaged to Mr. Rivenhall at a moment when he was exacerbated by his father’s excesses, her gentle words had fallen on fruitful soil. A naturally joyless nature, reared on bleak principles, could perceive only the most deplorable tendencies in a lively family’s desire for enjoyment. Charles, wrestling with mountainous piles of bills, was much inclined to think that she was right. It was only since Sophy’s arrival that his sentiments seemed to have undergone a change. Miss Wraxton could not deceive herself into underrating Sophy’s ruinous influence upon Charles’s character; and since she was not, in spite of her learning, very wise, she tried to counteract it in a variety of ways that served merely to set up his back. When she inquired whether Sophy had offered him an explanation of her visit to Rundell and Bridge, and, in justice to his cousin, he felt himself obliged to tell her some part of the truth, her evil genius had inspired her to point out to him the total unreliability of Hubert’s character, his resemblance to his father, and the ill-judged nature of Sophy’s admittedly good-natured conduct in the affair.

But Mr. Rivenhall was already writhing under the lash of his own conscience, and since, with all his faults, he was not one to burke a clear issue, these remarks found no favor with him. He said, “I blame myself. That any hasty words of mine should have made Hubert feel that anything would be preferable to confiding his difficulties to me must be an everlasting reproach to me! I have to thank my cousin for showing me how much I have erred! I hope I may do better in the future. I had no intention — but I see now how unsympathetic I must have appeared to him! I’ll take good care poor little Theodore does not grow up in the belief that he must at all costs conceal his peccadilloes from me!”

“My dear Charles, I assure you this is an excess of sensibility!” Miss Wraxton said soothingly. “You are not to be held accountable for the behavior of your brothers!”

“You are wrong, Eugenia. I am six years older than Hubert, and since I knew — none better — that my father would never concern himself with any one of us, it was my duty to take care of the younger ones! I do not scruple to say this to you, for you know how we are circumstanced!”

She replied without hesitation, “I am persuaded you have always done your duty! I have seen how you have tried to introduce into your father’s household more exact standards of conduct, a greater notion of discipline and of management. Hubert can have been in no doubt of your sentiments upon this occasion, and to condone his behavior — which I must think quite shocking — would be most improper. Miss Stanton-Lacy’s intervention, which was, of course, meant in the kindest way, sprang from impulse and cannot have been dictated by her conscience. Painful though it might have been to her, there can be no doubt that it was her duty to have told you the whole, and immediately! To have paid off Hubert’s debts in that fashion was merely to encourage him in his gaming propensities. I fancy that a moment’s reflection must have convinced her of this, but, alas, with all her good qualities, I fear that Miss Stanton-Lacy is not much given to the indulgence of rational thought!”

He stared at her, an odd expression in his eyes which she was at a loss to interpret. “If Hubert had confided in you, Eugenia, would you have come to me with his story?” he asked.

“Undoubtedly,” she replied. “I should not have known an instant’s hesitation.”

“Not an instant’s hesitation!” he repeated. “Although it was a confidence made in the belief that you would not betray it?”

She smiled at him. “That, my dear Charles, is a great piece of nonsense. To be boggling at such a thing as that when one’s duty is so plain is what I have no patience with! My concern for your brother’s future career must have convinced me that I had no other course open to me than to divulge his wrongdoing to you. Such ruinous tendencies must be checked, and since your father, as you have said, does not concern himself with — ”

He interrupted her without apology. “These sentiments may do honor to your reason but not to your heart, Eugenia! You are a female; perhaps you do not understand that a confidence reposed in you must — must — be held sacred! I said that I wished she had told me, but it was untrue! I could not wish anyone to betray a confidence! Good God, would I do so myself?”

These rapidly uttered words brought a flush to her cheek; she said sharply, “I collect that Miss Stanton-Lacy — I presume she is also a female — does understand this?”

“Yes,” he replied, “she does. Perhaps that is one of the results of her upbringing! It is an excellent one! Perhaps she knew what must be the result of her action; perhaps she only went to Hubert’s rescue from motives of generosity. I don’t know that; I have not inquired of her! The outcome has been happy — far happier than would have been the case had she divulged all to me! Hubert is too much of a man to shelter behind his cousin; he confessed the whole to me!”

She smiled. “I am afraid your partiality makes you a trifle blind, Charles! Once you had discovered that Miss Stanton-Lacy had sold her jewelry you were bound to discover the rest! Had I not been in a position to apprise you of this circumstance, I wonder if Hubert would have confessed?”

He said sternly, “Such a speech does you no credit! I do not know why you should be so unjust to Hubert, or why you should so continually wish me to think ill of him! I did think ill of him, and I have been proved wrong! Mine has been the fault; I treated him as though he were still a child and I his mentor. I should have done better to have taken him into my counsels. None of this would have happened had he and I been better friends. He said to me, had we been better acquainted — ! You may judge of my feelings upon hearing that from my brother!” He gave a short laugh. “A leveler indeed! Jackson himself could not have floored me more completely!”

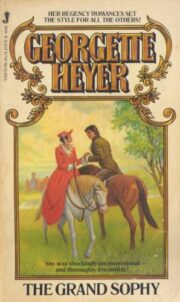

"The Grand Sophy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Grand Sophy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Grand Sophy" друзьям в соцсетях.