Watching two women exchange such a passionate kiss was a little icky but also completely satisfying. Lucy backed away to give them privacy.

Chapter Twenty-three

WITH THE EXCEPTION OF A man walking with a dog, Lucy had the beach to herself. Smaller and less accessible than the south beach, this spot on the west side of the island was mainly used by the locals, but even though it was Saturday, a thickly overcast sky had kept all but a few away. She’d settled in a sheltered spot at the base of a sand dune, her chin resting on her bent knees. Max had arrived two days earlier, and she and Temple had left yesterday afternoon. This morning, Kristi had taken off. Lucy was going to miss them. Maybe that accounted for her melancholy mood. She was making steady progress with her writing, so she had no reason to feel depressed about her work. By mid-September, she should finally be able to leave the island.

She sensed someone approaching. Her heart skipped a beat as she saw Panda walking toward her. Toby must have told him where she was.

Even though the sun had buried itself beneath the clouds, he wore dark glasses. He was clean-shaven, but his hair had grown wilder in the eleven days since she’d last seen him. It seemed like months. The knowledge she worked so hard to suppress struggled toward the surface. She shoved it back into the darkest recesses inside her where it could do no harm. While her own heart raced, he ambled toward her as casually as a tourist out for an evening stroll.

If he was mad at her for running out on him, it didn’t show. He nodded and took in her shorter hair, no longer quite as dark but still not back to her natural light brown color. She wasn’t wearing makeup, her fingernails were a wreck, and she hadn’t shaved her legs in a couple of days, but she didn’t let herself tuck them under her hips.

They gazed at each other, maybe only a few seconds, but longer than she could bear. She pretended to examine a trio of ladybugs crawling along a piece of driftwood. “Come to say good-bye?”

He stuffed a hand in the pocket of his shorts. “I’m leaving in the morning.” He gazed out at the water, as if he couldn’t stand looking at her longer than he needed to. “I’m starting a new job in a week.”

“Great.”

Another uncomfortable silence fell between them. At the water’s edge, the beach-walker tossed a stick into the lake, and his dog went after it. Whether she wanted to or not, there were things she needed to say before he left. “I hope you understand why I had to move out.”

He sat in the sand next to her and pulled a knee up, leaving a wide space between them. “Temple explained it to me. She said it was because I was an asshole.”

“Not true. If it hadn’t been for you that night—” She dug her toes into the sand. “I don’t like to think about it.”

He picked up a beach stone and rolled it in his palm. The dune grasses bent toward him as if they wanted to stroke his hair. She looked away. “Thanks for what you did.”

“I don’t need any more thanks,” he said gruffly.

She rubbed her arm, her skin gritty beneath her fingers. “I’m glad you told me about your brother.”

“I wanted to take your mind off what happened, that’s all.”

She pushed her feet deeper into the sand. “I think you should tell Bree about Curtis before you leave.”

He dropped the beach stone. “That her old man had no conscience? Not going to happen.”

“She’s a big girl. She knows he screwed around on her mother, and she needs to know about this. Let her decide whether or not to tell her brothers.”

The stubborn set of his jaw told her she was wasting her breath. She poked at a zebra mussel shell, feeling as undesirable as this invasive Great Lakes intruder. “With everything that happened, I never asked why you came back to the bar.”

“To get my car. I was pissed with you.”

“I made such a fool of myself that night. All summer, really, with my badass act.”

“It wasn’t an act. You are a badass.”

“Not true, but thanks.” She sifted some sand through her fingers. “One good thing came out of the experience. I learned that trying to slide into another skin wouldn’t fix me.”

“Who says you need fixing?” He displayed a comforting degree of indignation. “You’re fine just the way you are.”

She bit the inside of her lip. “Thanks.”

Another long silence fell, an awful, unbreachable chasm that spoke volumes about the distance that had grown between them. “How’s your writing going?” he asked.

“Pretty well.”

“That’s good.”

More silence, and then he rose. “I need to finish packing. I came here to tell you that you’re free to stay at the house when I leave.”

That was the only reason? Her chest aching, she looked up and saw her reflection in his dark glasses. “I’m fine at Bree’s,” she said stiffly.

“You care about the place more than I do. If you change your mind, here’s a key.”

She didn’t reach for it—couldn’t make herself—so he dropped it in her lap. It landed on the hem of her shorts, the yellow happy-face key fob staring up at her.

He reached for his sunglasses, as if he were going to take them off, but changed his mind. “Lucy, I—” The stubbornness she knew so well thinned his lips. He rested a hand on his hip and dipped his head. The words that emerged were as rough as if he’d rubbed them with sandpaper. “Stay safe, okay?”

That was all. He didn’t look at her again. Didn’t say more. Simply walked away.

Her fingers curled into fists. She squeezed her eyes shut, too angry to cry. She wanted to throw herself at his back and wrestle him to the ground. Slap and kick. The callous, unfeeling bastard. After everything that had happened, after everything they’d said and done, this was his exit line.

She finally managed to make her way back to the parking lot. She biked to the house, peddling as furiously as Miss Gulch on her way to collect Toto. No wonder he’d never come to the cottage to check up on her. Out of sight, out of mind. That was Patrick Shade’s way.

Bree was at the farm stand. She took one look at Lucy’s face and set aside her paintbrush. “What happened?”

It was over. Finished. Accept it. “Life,” Lucy retorted. “It sucks.”

“Tell me about it.”

Lucy resisted the urge to hurl her bike across the driveway. “I need to get out. Let’s have dinner at the Island Inn. Just the two of us. My treat.”

Bree looked around at the farm stand. “I don’t know … It’s Saturday night. There’s a fish fry on the south beach, so there’ll be a lot of traffic …”

“We won’t be gone long. Toby can handle things for a couple of hours. You know how much he loves being a big shot.”

“True.” She cocked her head. “All right. Let’s do it.”

Lucy stomped around the small bedroom where she’d been staying. Eventually she forced herself to open the matchbox closet and study the clothes Temple had brought over. But she couldn’t go back to her Viper outfits, and she didn’t have much else with her. Even if the closet had held her old Washington wardrobe, the tailored suits and pearls wouldn’t have felt any more right than Viper’s green tutu and combat boots.

She ended up in jeans with a breezy linen blouse she borrowed from Bree. As they left, Bree stopped her car at the end of the drive to throw last-minute instructions out the driver’s window. “We won’t be gone long. Remember to ask people to be careful with the ornaments.”

“You already told me that.”

“Watch the change box.”

“You told me that about a thousand times.”

“Sorry, I …”

“Go,” Lucy ordered, gesturing toward the highway.

With one last worried glance, Bree reluctantly stepped on the gas.

Lucy hadn’t come into town since she’d cut her dreads from her hair and scrubbed off her tattoos, and Bree automatically took the chair that looked out into the dining room so Lucy could face the wall. But it had been almost three months since her wedding, the story had died down, and Lucy couldn’t bring herself to care whether or not anyone recognized her.

They ordered grilled portabellas and a barley salad sweetened with peaches. Lucy gulped down her first glass of wine and started on her second. The food was well prepared, but she had no appetite, and neither, it seemed, did Bree. By the time they drove back to the cottage, they’d given up the effort to make conversation.

The farm stand came into sight. At first they didn’t notice anything was wrong. Only as they came closer did they see the destruction.

Toby stood in a sea of broken honey bottles—far more bottles than had been out on display. He turned in a jerky, aimless circle, the honey-splattered quilt Bree tossed over the counter hanging from one hand, his game player in the other. He froze as he saw the car.

Bree jumped out, the motor still running, a scream ripping from her throat. “What happened?”

Toby dropped the quilt into the mess. The Adirondack chairs lay on their sides near the splintered remains of the Carousel Honey sign. The door of the storage shed that jutted off the back gaped open, its shelves emptied of several hundred bottles of next year’s crop Bree had stashed there to give her more working room in the honey house. Toby was streaked from head to toe with honey and dirt. A trickle of blood ran down his hand from broken glass. “I only left for a minute,” he sobbed. “I didn’t mean—”

“You left?” She charged forward, her shoes crunching in the glass.

“Only for a minute. I-I had to get my N-Nintendo. Nobody was stopping!”

Bree saw what he was holding, and her hands fisted at her sides. “You left to get a video game?”

“I didn’t know—I didn’t mean—It was only for a minute!” he cried.

“Liar!” Her eyes blazed. “All this didn’t happen in a minute. Go! Get out of here!”

Toby fled toward the cottage.

Lucy had already turned off the engine and jumped out of the car herself. The wooden shelves hung askew, and broken honey bottles were everywhere, even out on the highway. Shattered lotion jars spattered the drive; the luxurious creams and scented potions smearing the gravel. The cash box was gone, but that wasn’t as devastating as the loss of hundreds of bottles of next year’s crop. The glass from the bottles mingled with the silver shards of Bree’s precious, fragile Christmas ornaments.

Bree knelt, her skirt trailing in the muck, and cradled what was left of a delicate globe. “It’s over. It’s all over.”

If Lucy hadn’t insisted they go out this evening, none of this would have happened. She couldn’t think of anything comforting to say. “Why don’t you go inside? I’ll deal with the worst of this.”

But Bree wouldn’t leave. She stayed crouched over the debris of goo, glass, and ruined dreams.

With guilt hanging over her head like a shroud, Lucy fetched a pair of rakes and a shovel. “We’ll figure out something tomorrow,” she said.

“There’s nothing to figure out,” Bree whispered. “I’m done.”

LUCY MADE BREE CALL THE police. While Bree told them what had happened in a flat, listless voice, Lucy began scraping the worst of the glass back from the highway. Bree finished answering their questions and hung up. “They’re coming out tomorrow to talk to Toby.” Her expression hardened. “I can’t believe he let this happen. It’s unforgivable.”

It was too early to plead Toby’s case, and Lucy didn’t try. “It’s my fault,” she said. “I’m the one who insisted we go out.” Bree brushed away her apology with a shaky hand.

They worked in the ghostly illumination of a pair of floodlights mounted on the front of the farm stand. Cars slowed as they passed, but no one stopped. Bree dragged away her splintered sign. They righted the chairs, tossed the damaged candles and ruined note cards into trash bags. As night settled in, they began attacking the broken glass with rakes, but the ocean of ruined honey made the glass stick to the tines, and a little after midnight Lucy pulled the rake from Bree’s hands. “That’s enough for now. I’ll bring a hose out in the morning and spray everything down.”

Bree was too demoralized to argue.

They walked back to the house in silence. They had honey everywhere—on their skin, on their clothes, in their hair. Clumps of dirt and grass stuck to their arms and legs, along with slivers of glass and other muck. As Lucy peeled off her sandals, she saw a square of pale blue cardboard stuck to the heel.

I’m a one-of-a-kind Christmas ornament.

Please be careful when you pick me up.

They took turns sticking their feet under the outside faucet. Bree leaned down to rinse off her hands and forearms, then glared toward the back window. “I can’t talk to him right now.”

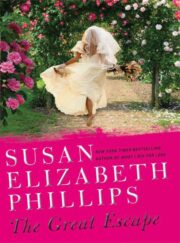

"The Great Escape" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Great Escape". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Great Escape" друзьям в соцсетях.