She’d let herself fall in love with him. Against all reason, all common sense, she’d fallen deeply in love with this emotionally stunted man who couldn’t love her back.

She ended up in the boat, not curled asleep in the bow where Toby had hidden himself, but sitting up, wide awake—the whole furious, sticky, heartbroken mess of her.

Chapter Twenty-five

HIS CAR WAS GONE THE next morning, along with him. Lucy stumbled into the house, threw her clothes into the washer, and took a shower, but she had a splitting headache and she didn’t feel any better when she came out.

All she could find to wear was her black bathing suit and one of his T-shirts. She wandered through the empty house barefoot. He’d taken most of his clothes, his work folders, and the commuter coffee mug he carried around in the morning. So many emotions overwhelmed her, each one more painful than the last—her pity for what he’d been through; her anger at the universe, at herself, for falling in love with such a damaged man. And her anger at Panda.

Despite his words, he’d misled her. With every tender touch, every shared glance and intimate smile, she’d felt him telling her he loved her. Lots of men had been through traumatic experiences, but that didn’t mean they ran away.

Her anger made her feel better, and she nursed it. She couldn’t afford to pity him or herself. Far better to turn that pity into antagonism. Run, you coward. I don’t need you.

She decided to move back into his house that same day.

Despite her misery, she couldn’t forget her promise to help Bree clean up from last night’s vandalism, but before she could get to the cottage, Mike called and told her that he and Toby were handling the mess—no girls allowed. She didn’t protest.

She waited until afternoon to get her things from the cottage. She discovered a dreamy-eyed Bree sitting at the kitchen table with a notepad, an equally infatuated Mike at her side. The faint beard-burn on Bree’s neck and Mike’s tender, proprietary manner didn’t leave much doubt about what the two of them had been up to last night while Toby slept.

“You can’t leave,” Bree said when Lucy revealed her intention. “I’m working on a plan to save my business, and I’m going to need you more than ever.”

Mike tapped a legal pad covered with notes in Bree’s precise handwriting. “We don’t want you in that big house by yourself,” he said. “We’ll worry about you.”

But the two of them could barely take their eyes off each other long enough to talk to her, and Toby was no better. “Mike and Bree are getting married!” he announced when he came into the kitchen.

Bree smiled. “Settle down, Toby. Nobody’s getting married to anybody yet.”

The looks Mike and Toby exchanged suggested they had other ideas about that.

Lucy wouldn’t spoil their happiness with her own misery. She promised to come over the next afternoon and waved good-bye.

She continued to nourish her anger, but after a few days of furious, solitary walks and lengthy bike rides that still didn’t wear her out enough to sleep, she knew she had to do something else. Finally she opened the laptop Panda had left behind and got back to work. At first she couldn’t concentrate, but gradually she found the distraction she needed.

Maybe it was the pain from her breakup with Panda, but she found herself thinking more and more about the earlier pain she’d endured from spending the first fourteen years of her life with a biological mother who was a professional party girl.

“Lucy, I’m going out tonight. The door’s locked.”

“I’m scared. Stay here.”

“Don’t be a baby. You’re a big girl now.”

But she hadn’t been a big girl—she’d been eight—and over the next few years, she’d become the only responsible person in their dismal household.

“Lucy, damn it! Where’s that money I hid in the back of my drawer?”

“I used it to pay the damn rent! Do you want us to get kicked out again?”

She’d always believed her sense of responsibility had begun after Sandy had died, when she’d had to take care of Tracy on her own, but now she understood it had begun long before that.

She wrote until her muscles cramped, but she couldn’t write forever, and as soon as she stopped, heartache overwhelmed her. That was when she tightened her cloak of anger. With it firmly in place, she could keep breathing.

PANDA HAD BEEN LOOKING FORWARD to his new job managing security for a big-budget action film shooting in Chicago, but two days after he started, he got the flu. Instead of staying in bed where he belonged, he worked through the fever and chills only to end up with pneumonia. He worked through that, too, because going to bed with nothing to think about except Lucy Jorik wasn’t an option.

Be the best at what you’re good at … A great motto right up to the day he’d met her.

“You’re an ass,” Temple told him during one of her too-frequent phone calls. “You had a chance at happiness, and you ran from it. Now you’re trying to self-destruct.”

“Just because you think you’ve gotten your life together doesn’t mean everybody wants to,” he retorted, glad she couldn’t see how gaunt he looked, how tense he was.

He had more job offers than he could handle, so he hired two former cops to work for him. He sent one on an assignment in Dallas, the other to babysit a teen actor in L.A.

Temple called again. He dug into his pocket for a tissue to blow his nose and jumped in before she could harangue him about Lucy. “How’s filming the new season going?”

“Other than having the producers constantly screaming at Kristi and me,” she said, “it’s going great.”

“The two of you put them over a barrel. You’re lucky they didn’t have time to replace you or you’d both be looking for new jobs.”

“They’d have been sorry,” Temple retorted. “Audiences were getting bored with the old show, and they’re going to love this new approach. It’s got heart. Kristi still has to wear her red bikini, but she has a lot more screen time, and she’s using it brilliantly.” He heard her crunch into something. An apple? A piece of celery? The cookie she allowed herself each day? “I’ve made the workouts so much more fun,” she said. “And I actually cried today! Real tears. That’s going to be ratings gold.”

“I have a lump in my throat just thinking about it.” His drawl turned into a cough he quickly muffled.

“No, really,” she said. “This contestant—her name’s Abby—she was abused horribly as a child. It just … got to me. They all have stories. I don’t know why I didn’t take the time to listen more closely before.”

He knew why. Paying attention to other people’s fears and insecurities might have forced her to examine her own, and she hadn’t been ready to do that.

She went on, mouth full. “Usually after a couple of weeks filming, I’m hoarse from screaming at people, but listen to me.”

“I’m doing my best not to.” He took a slug of water to suppress another coughing fit.

“I thought Lucy was crazy when she talked about her ‘Good Enough’ approach to exercise, but she hit on something. I’m working on a long-term exercise program that’s more realistic. And … Get this … We have a great hidden-camera segment where we teach the audience how to read food labels by staging these phony fights in supermarket aisles.”

“That’ll get you an Emmy for sure.”

“Your bitterness isn’t attractive, Panda. Mock as much as you want, but we’re finally going to be able to help people long term.” And then, because she still wanted him to think she was as tough as ever, “Call Max back. She’s left three voice mails, and you haven’t returned any of them.”

“Because I don’t want to talk to her, either,” he grumbled.

“I phoned Lucy yesterday. She’s still at the house.”

Another call buzzed in, which gave him an excuse to hang up on her. Unfortunately, this call came from Kristi. “No time to talk,” he said.

She ignored him. “Temple was amazing in our interview. Completely raw and open.”

It took him a moment to figure out she was talking about the lengthy counseling session she and Temple had just finished filming. The producers planned to use it to kick off the new season, knowing Temple’s lesbian revelation would kick up a storm of extra publicity.

“We bring Max on toward the end,” Kristi said, “and watching the two of them together is enough to soften the hardest hearts. Audiences are going to love this new side of her. And I got to wear a dress.”

“A tight one, I’ll bet.”

“You can’t have everything.”

“I only want one thing,” he growled. “I want you and your she-devil friend to leave me the hell alone.”

A brief, censorious pause. “You could live a more authentic life, Panda, if you’d do what I’ve advised and stopped transferring your anger to other people.”

“I’m hanging up now so I can find a window high enough to jump out of.”

But as much as he complained about them, some days it felt as if their intruding phone calls were all that kept him anchored. These women cared about him. And they were his only fragile link to Lucy.

FALL CAME EARLY TO CHARITY Island. The tourists disappeared, the air grew crisp, and the maples began to display their first blush of crimson. The writing that had once been such a struggle for Lucy turned out to be her salvation, and she was finally able to send off her completed manuscript to her father.

She spent the next few days biking around the island and walking the empty beaches. She wasn’t sure exactly when it had happened, but through her pain and her anger, she’d somehow figured out how she intended to shape her future.

No more of the lobbying she detested. She was going to listen to her heart and once again work one-on-one with kids. But that couldn’t be all. Her conscience dictated that she keep using her secondhand fame to advocate on a larger scale. This time she intended to do that through something that truly fulfilled her—through her writing.

When her brutally honest newspaperman father read the manuscript and called her, he confirmed what she already knew. “Luce, you’re a real writer.”

She was going to write her own book, not about herself or her family, but about real kids in peril. It wouldn’t be some dry, academic tome, but a page-turner full of personal stories from kids, from counselors, all with the goal of shining a brighter spotlight on the welfare of the most vulnerable. Her name on the spine would guarantee plenty of publicity. That meant thousands of people—maybe hundreds of thousands—who knew nothing about disadvantaged kids would gain real insight into the issues they faced.

But having a clearer direction didn’t bring her the peace she craved. How could she have let herself fall in love with him? A bitter knot burned so fiercely in the center of her chest that she sometimes felt as though she’d burst into flames.

With the manuscript mailed off and October fast approaching, she called her mother’s press secretary, who hooked her up with a reporter from the Washington Post. On the next-to-last day of September, Lucy sat in the sunroom, her phone pressed to her ear, and gave the interview she’d been avoiding.

It was humiliating … I panicked … Ted is one of the finest men I’ve ever met … spent the last few months working on my father’s book and trying to get my bearings back … going to be writing my own book … advocate for kids who have no voice …

She didn’t mention Panda.

After the interview, she called Ted and had the conversation she couldn’t have had with him before. Then she began to pack.

Bree had been to her old vacation house several times since Lucy had moved back in, and she came over the day after the interview to help her close up. In only a few months, she, Toby, and Mike had become woven into the fabric of Lucy’s life, and she knew she’d miss them. But as close as she felt to Bree, Lucy couldn’t talk to her about Panda, couldn’t talk to anybody, not even Meg.

Bree perched on the counter, watching Lucy clean out the big stainless steel refrigerator. “It’s funny,” she said. “I thought coming inside this house would destroy me, but all it does is make me nostalgic. My mother fixed so many bad dinners in this kitchen, and Dad’s grilling didn’t help. He burned everything.”

Bree’s father had done a lot worse than burn hamburgers, but that wasn’t Lucy’s story to tell. She held up a barely used jar of mustard. “Want this?”

Bree nodded, and Lucy set the mustard in a cardboard box, along with the other leftover groceries she was sending to the cottage.

Bree pushed the sleeves up on the heavy sweater she was wearing against the early fall chill. “I feel like a woman of leisure not having to spend all day at the farm stand.”

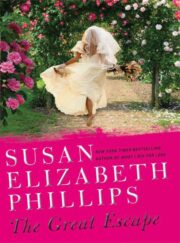

"The Great Escape" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Great Escape". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Great Escape" друзьям в соцсетях.