“She deserves all that,” he agreed, patting her shoulder. “She’ll have it, too, Morgan. I promise you she’ll have what she wants.”

When Val and Dev joined him in the library less than an hour later, Anna was still unpacking while Morgan was busy packing. The earl explained what he knew of the situation, pleased to hear the magistrate had agreed to delay Stull’s bond hearing for another two days.

“That gives us time to get Morgan to Their Graces,” the earl said, glancing at Val. “Unless you object?”

“It wouldn’t be my place to object,” Val said, his lips pursed, “but I happen to concur. Morgan can use some pampering, and Her Grace feels miserable for having set Hazlit on their trail. This will allow expiation of Her Grace’s sins, and distract His Grace, as well.”

“Creates a bit of a problem for you,” Dev pointed out.

“How so?” Val frowned.

“How are you going to continue to convince our sire you are a mincing fop, when every time Morgan walks by, you practically trip over your tongue?”

“My tongue, Dev, not my cock. If you could comprehend the courage it takes to be deaf and mute in a society that thinks it is neither, you would be tripping at the sight of her, as well.”

Dev spared a look at the earl, who kept his expression carefully neutral.

“You will both escort Morgan to Their Graces later this afternoon,” Westhaven said. “For now, I’d like you to remain here, keeping an eye on Anna.”

“You don’t trust her?” Dev asked, censorship in his tone.

“She gave her word not to run, but I am not convinced Stull was the only threat to her. Her own brother got her involved in this scheme with Stull, and he’s the one who benefits should Stull get his hands on Anna. Where is Helmsley, and what is his part in this?”

“Good question,” Dev allowed. “Go call on Their Graces, then, and leave the ladies in our capable hands.”

Val nodded. “His Grace will be flattered into a full recovery to think you’d entrust a damsel in distress to his household.”

The earl nodded, knowing it was a good point. Still, he was sending Morgan to the duke and duchess because their home was safe, a near fortress, with servants who knew better than to allow strangers near the property or the family members. And it was nearby, which made getting Morgan there simple. Then, too, Anna saw the wisdom of it, making it one less issue he had to argue and bully her through.

He found Anna in her sitting room, sipping tea, the evil valise nowhere in sight.

“I’m off to Moreland House,” the earl informed her, “to ask Their Graces to provide Morgan sanctuary. I will ask on your behalf, as well, if it’s what you want.”

“Do you want me to go with her?” Anna asked, her gaze searching his.

“I do not,” he said. “It’s one thing to ask my father and mother to keep Morgan safe, when Stull isn’t even sure she’s in London. It’s another to ask them to keep you safe, when I am on hand to do so and have already engaged the enemy, so to speak.”

“Stull isn’t your enemy,” Anna said, dropping her gaze. “If it hadn’t been him, my brother would have found somebody else.”

“I am not so convinced of that, Anna.” The earl lowered himself into a rocking chair. “The society in York is provincial compared to what we have here in London. My guess is that there were likely few willing to collude with your brother in defrauding your grandfather’s estate, shackling you and Morgan to men you found repugnant and impoverishing your sickly grandmother into the bargain.”

“That is blunt speech,” she said at length.

“I am angry, Anna.” The earl rose again. “I fear diplomacy is beyond me.”

“Are you angry with me?”

“Oh, I want to be,” he assured her, his gaze raking her up and down. “I want to be furious, to turn you over my knee and paddle you until my hand hurts, to shake you and rant and treat the household to a tantrum worthy of His Grace.”

“I am sorry.” Anna’s gaze dropped to the carpet.

“I am not angry with you,” the earl said gravely, “but your brother and his crony will have much to answer for.”

“You are disappointed in me.”

“I am concerned for you,” the earl said tiredly. “So concerned I am willing to seek the aid of His Grace, and to pull every string and call in every favor the old man can spare me. Just one thing, Anna?”

She met his gaze, looking as though she was prepared to hear the worst: Pack your things, get out of my sight, give me back those glowing characters.

“Be here when I get back,” the earl said with deadly calm. “And expect to have a long talk with me when this is sorted out.”

She nodded.

He waited to see if she had anything else to add, any arguments, conditions, or demurrals, but for once, his Anna apparently had the sense not to fight him. He turned on his heel and left before she could second guess herself.

Sixteen

“I HAVE COME TO SEEK ASSISTANCE,” WESTHAVEN SAID, meeting his father’s gaze squarely. The duke was enjoying his early afternoon tea on the back terrace of the mansion, and looking to his son like a man in a great good health.

“Seems to be the season for it,” the duke groused. “Your dear mother will hardly let me chew my meat without assistance. You’d best have a seat, man, lest she catch me craning my neck to see you.”

“She means well,” the earl said, his father’s response bringing a slight smile to his lips.

The duke rolled his eyes. “And how many times, Westhaven, has she attempted to placate your irritation with me, using that same phrase? Tea?”

“More than a few,” the earl allowed. “She doesn’t want to lose you, though, and so you must be patient with her. And yes, a spot of tea wouldn’t go amiss.”

“Patient!” the duke said with a snort. He poured his son a cup and added a helping of sugar. “That woman knows just how far she can push me, with her Percy this and dear heart that. But you didn’t come here to listen to me resent your mother’s best intentions. What sort of assistance do you need?”

“I’m not sure,” Westhaven said, accepting the cup of tea, “but it involves a woman, or two women.”

“Well, thank the lord for small favors.” The duke smiled. “Say on, lad. It’s never as bad as you think it is, and there are very few contretemps you could get into I haven’t been in myself.”

At his father’s words, a constriction weighting Westhaven’s chest lifted, leaving him able to breathe and strangely willing to enlist his father’s support. He briefly outlined the situation with Anna and Morgan, and his desire to keep Morgan’s whereabouts unknown.

“Of course she’s welcome.” The duke frowned. “Helmsley’s granddaughter? I think he was married to that… oh, Bellefonte’s sister or aunt or cousin. Your mother will know. Bring her over; the girls will flutter and carry on and have a grand time.”

“She can’t leave the property,” Westhaven cautioned. “Unless it’s to go out to Morelands in a closed carriage.”

“I am not to leave Town until your quacks allow it,” the duke reported. “There’s to be no removing to the country just yet for these old bones, thank you very much.”

“How are you feeling?” the earl asked, the question somehow different from all the other times he’d asked it.

“Mortality,” the duke said, “is a daunting business, at first. You think it will be awful to die, to miss all the future holds for your loved ones, for your little parliamentary schemes. I see now, however, that there will come a time when death will be a relief, and it must have been so for your brother Victor. At some point, it isn’t just death; it’s peace.”

Shocked at both the honesty and the depth of his father’s response, Westhaven listened as he hadn’t listened to his father in years.

“My strength is returning,” the duke said, “and I will live to pester you yet a while longer, I hope, but when I was so weak and certain my days were over, I realized there are worse things than dying. Worse things than not securing the bloody succession, worse things than not getting the Lords to pass every damned bill I want to see enacted.”

“What manner of worse things?”

“I could never have known your mother,” the duke said simply. “I could linger as an invalid for years, as Victor did. I could have sent us all to the poor house and left you an even bigger mess to clean up. I guess”—the duke smiled slightly—“I am realizing what I have to be grateful for. Don’t worry…” The smile became a grin. “This humble attitude won’t last, and you needn’t look like I’ve had a personal discussion with St. Peter. But when one is forbidden to do more than simply lie in bed, one gets to thinking.”

“I suppose one does.” The earl sat back, almost wishing his father had suffered a heart seizure earlier in life.

“Now, about your Mrs. Seaton,” the duke went on. “You are right; the betrothal contracts are critical but so are the terms of the guardianship provisions in the old man’s will. In the alternative, there could be a separate guardianship document, one that includes the trusteeship of the girl’s money, and you have to get your hands on that, as well.”

“Not likely,” the earl pointed out. “It was probably drawn up in York and remains in Helmsley’s hands.”

“But he will have to bring at least the guardianship papers with him if he’s to retrieve his sisters. You say they are both over the age of eighteen, but the trust document might give him control of their money until they marry, turn five and twenty, or even thirty.”

“I can ask Anna about that, but I have to ask you about something else.”

The duke waited, stirring his tea while Westhaven considered how to put his question. “Hazlit has pointed out I could protect Anna by simply marrying her. Would you and Her Grace receive her?”

In a display of tact that would have made the duchess proud and quite honestly impressed Westhaven, the duke leaned over and topped off both tea cups.

“I put this question to your mother,” the duke admitted, “as my own judgment, according to my sons, is not necessarily to be trusted. I will tell you what Her Grace said, because I think it is the best answer: We trust you to choose wisely, and if Anna Seaton is your choice, we will be delighted to welcome her into the family. Your mother, after all, was not my father’s choice and no more highly born than your Anna.”

“So you would accept her.”

“We would, but Gayle?”

His father had not referred to him by name since Bart’s death, and Westhaven found he had to look away.

“You are a decent fellow,” the duke went on, “too decent, I sometimes think. I know, I know.” He waved a hand. “I am all too willing to cut corners, to take a dodgy course, to use my consequence at any turn, but you are the opposite. You would not shirk a responsibility if God Almighty gave you leave to do so. I am telling you, in the absence of the Almighty’s availability: Do not marry her out of pity or duty or a misguided sense you want a woman in debt to you before you marry her. Marry her because you can’t see the rest of your life without her and you know she feels the same way.”

“You are telling me to marry for love,” Westhaven concluded, bemused and touched.

“I am, and you will please tell your mother I said so, for I am much in need of her good graces these days, and this will qualify as perhaps the only good advice I’ve ever given you.”

“The only good advice?” Westhaven countered. “Wasn’t it you who told me to let Dev pick out my horses for me? You who said Val shouldn’t be allowed to join up to keep an eye on Bart? You who suggested the canal project?”

“Even a blind hog finds an acorn now and then,” the duke quipped. “Or so my brother Tony reminds me.”

“I will get my hands on those contracts.” The earl rose. “And the guardianship and trust documents, as well, if you’ll keep Morgan safe.”

“Consider it done.” The duke said, rising. “Look in on your mama before you go.”

“I will,” Westhaven said, stepping closer and hugging his father briefly. To his surprise, the duke hugged him right back.

“My regards to St. Just.” The duke smiled winsomely. “Tell him not to be a stranger.”

“He’ll come over with Val this evening,” Westhaven said, “but I will pass along your felicitations.”

The duke watched his heir disappear into the house, not surprised when a few minutes later the duchess came out to join him.

“You should be napping,” his wife chided. “Westhaven was behaving peculiarly.”

“Oh?” The duke slipped an arm around his wife’s waist. “How so?”

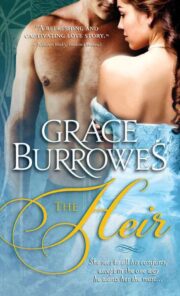

"The Heir" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Heir". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Heir" друзьям в соцсетях.