CHAPTER NINETEEN

IT WAS SNOWING. The soft flakes fell upon my head and my hands, and the world all about me was suddenly white, no lush green summer grass, no line of trees, and the snow fell steadily, blotting the hills from sight. There were no farm-buildings anywhere near me — nothing but the black river, about twenty foot broad where I was standing, and the snow, which had drifted high on either bank, only to slither into the water as the mass caved in from the weight, revealing the muddied earth beneath. It was bitter cold; not the swift, cutting blast that sweeps across high ground, but the dank chill of a valley where winter sunshine does not penetrate, nor cleansing wind. The silence was the more deadly, for the river rippled past me without sound, and the stunted willows and alder growing beside it looked like mutes with outstretched arms, grotesquely shapeless because of the burden of snow they bore upon their limbs. And all the while the soft flakes fell, descending from a pall of sky that merged with the white land beneath.

My mind, usually clear when I had taken the drug, was stupefied, baffled; I had expected something akin to the autumn day that I remembered from the previous time, when Bodrugan had been drowned, and Roger carried the dripping body in his arms towards Isolda. Now I was alone, without a guide; only the river at my feet told me I was in the valley. I followed its course upstream, groping like a blind man, knowing by instinct that if I kept the river on my left I must be moving north, and that somewhere the strip of water would narrow, the banks would close, and I should find a bridge or ford to take me to the other side. I had never felt more helpless or lost. Time, in this other world, had hitherto been calculated by the height of the sun in the sky, or, as when I traversed the Lampetho valley at night, by the stars overhead; but now, in this silence and beneath the falling snow, there was no means of gauging whether it was morning or afternoon. I was lost, not in the present, with familiar landmarks close at hand, the reassuring presence of the car, but in the past.

The first sound broke the silence, a splash in the river ahead, and moving swiftly I saw an otter dive from the further bank and swim his way upstream. As he did so a dog followed him, and then a second, and immediately there were some half-dozen of them yelping and crying at the river's brink, splashing their way into the water in chase of the otter. Someone shouted, the shout taken up by another, and a group of men came running towards the river through the falling snow, shouting, laughing, encouraging the dogs, and I saw they were coming from a belt of trees just beyond me, where the river curved. Two of them scrambled down the bank into the water, thrashing it with their sticks, and a third, holding a long whip, cracked it in the alr, stinging the ear of one of the dogs still crouching on the bank, which plunged after its companions.

I drew nearer, to watch them, and saw how the river narrowed a hundred yards or so beyond, while on the left, at the entrance to a copse of trees, the land fell away and the stream formed a sheet of water like a miniature lake, a film of ice upon its surface. Somehow the men and the dogs, between them, drove the hunted otter into the gulley that fed the lake, and in a moment they were upon him, the dogs crying, the men thrashing with their sticks. The dogs floundered as the ice cracked, the surface crimsoned, and blood spattered the film of white above black water as the otter, seized between snapping jaws, was dragged from the hole he sought, and torn to pieces where the ice held firm. The lake can have held little depth, for the men, hallooing and calling to the dogs, strode forward on to it, careless of the crack appearing suddenly from one end to the other. Foremost among them was the man with the long whip, who stood out from his fellows because of his height, and his dress as well, a padded surcoat buttoned to the throat and a high beaver hat upon his head, shaped like a cone. "Drive them clear," he shouted, to the bank on the further side. "I'd as soon lose the lot of you as one of these," and bending suddenly, amongst the pack of yelping hounds, he lifted what remained of the otter from the midst of them and flung it across the lake to the snow-covered verge. The dogs, baulked of their prey, struggled and slid across the ice to retrieve it where it now lay, while the men, less nimble than the animals, and hampered by their clothing, floundered and splashed in the breaking ice, shouting, cursing, jerkins and hoods caked white with the falling snowflakes.

The scene was part brutal, part macabre, for the man with the conical hat, once he knew his hounds were safe, turned his attention, laughing, to his companions in misfortune. While he himself was wet now to the thigh, he at least had boots to protect his feet, while his attendants, as I supposed they were, had some of them lost their shoes when the ice broke, and were thrashing about with frozen hands in useless search of them. Their master, laughing still, regained the bank, and, lifting his conical hat a moment, shook the snowflakes clear before replacing it once more. I recognised the ruddy face and the long jaw, although he was some twenty feet away. It was Oliver Carminowe. He was staring hard in my direction, and although reason told me he could not see me, and I had no part in his world, the way he stood there, motionless, his head turned towards me, disregarding his grumbling attendants, gave me a strange feeling of unease, almost of fear. "If you want to have speech with me, come across and say so," he called suddenly. The shock of what I thought discovery sent me forward to the lake's edge, and then, with relief I saw Roger standing beside me to become, as it were, my spokesman and my cover. How long he had been there I did not know. He must have walked behind me along the river bank.

"Greetings to you, Sir Oliver!" he cried. "The drifts are shoulder-high above Treesmill, and your side of the valley too, so Rob Rosgof's widow told me at the ferry. I wondered how you fared, and the lady Isolda too."

"We fare well enough," answered the other, "with food enough to last a siege of several weeks, which God forbid. The wind may change within a day or two and bring us rain. Then, if the road does not flood, we shall leave for Carminowe. As to my lady, she stays in her chamber half the day sulking, and gives me little of her company." He spoke contemptuously, watching Roger all the while, who moved nearer to the river bank. "Whether she follows me to Carminowe is her concern," he continued. "My daughters are obedient to my will, if she is not. Joanna is already promised to John Petyt of Ardeva, and, although a child still, prinks and preens before the glass as if she were already a bride of fourteen years and ripe for her strapping husband. You may tell her godmother Lady Champernoune so, with my respects. She may wish a like fortune for herself before many years have passed." He burst out laughing, and then, pointing to the hounds scavenging beneath the trees, said, "If you have no fear of fording the river where the plank has rotted, I will find an otter's paw which you may present to Lady Champernoune with my compliments. It may remind her of her brother Otto, being wet and bloody, and she can nail it on the walls of Trelawn as a memento to his name. The other paw I will deliver to my own lady for a similar purpose, unless the dogs have swallowed it." He turned his back and walked towards the trees, calling to his hounds, while Roger, moving forward up the river bank, and I beside him, came to a rough bridge, made out of lengths of log bound together, the whole slippery with the fallen snow, and partly sagging in the water. Oliver Carminowe and his attendants stood watching as Roger set foot upon the rotting bridge, and when it collapsed beneath his weight and he slipped and fell, soaking himself above his thighs, they roared in unison, expecting to see him turn again and claw the bank. But he strode on, the water coming nearly to his waist, and reached the other side, while I, dry-shod, followed in his wake. He walked directly to the edge of the copse where Carminowe stood, whip in hand, and said, "I will deliver the otter's paw, if you will give it to me."

I thought he would receive a lash from the whip across his face, and I believe he expected the same himself, but Carminowe, smiling, his whip raised, lashed suddenly amongst the dogs instead, and whipping them from the torn body of the otter took the knife from his belt, and cut off two of the remaining paws.

"You have more stomach than my steward at Carminowe," he said. "I respect you for that, if for nothing else. Here, take the paw, and hang it in your kitchen at Kylmerth, amongst the silver pots and platters you have doubtless stolen from the Priory. But first walk up the hill with us and pay your respects to Lady Carminowe in person. She may prefer a man, once in a while, to the tame squirrel she occupies her days with."

Roger took the paw from him and put it in his pouch, saying nothing, and we entered the copse and began threading our way through the snow-laden trees, walking steadily uphill, but whether to right or left I had no idea, having lost all sense of direction, knowing only that the river was behind us and the snow was falling still. A track packed high with snow on either side led to a stone-built house, tucked snugly against the hill; and, while Carminowe's attendants still straggled in our rear, he himself kicked open the door before us and we entered a square hall, to be greeted at once by the house-dogs, fawning upon him, and the two children, Joanna and Margaret, whom I had last seen riding their ponies across the Treesmill ford on a summer's afternoon. A third, somewhat older than the others, about sixteen, whom I took for one of Carminowe's daughters by his first marriage, stood smiling by the hearth, nor did she embrace him, but pouted with a sort of petulant grace when she saw he was not alone.

"My ward, Sybell, who seeks to teach my children better manners than their mother," Carminowe said.

The steward bowed and turned to the two children, who, after having kissed their father, came to welcome him. The elder, Joanna, had grown, and showed some sign of dawning self-consciousness, as her father had said, by blushing, and tossing her long hair out of her eyes, and giggling, but the younger, with still some years to go before she too ripened for the marriage-market, struck out her small hand to Roger and smote him on the knee.

"You promised me a new pony when last we met," she said, "and a whip like your brother Robbie's. I'll have no truck with a man who fails to keep his word."

"The pony awaits you, and the whip too," answered Roger gravely, "if Alice will bring you across the valley when the snow melts."

"Alice has left us," replied the child. "We have her to mind us now," and she pointed a disdainful finger at the ward Sybell, "and she's too grand to ride pillion behind you or Robbie."

She looked so much like her mother as she spoke that I loved her for it, and Roger must have seen the likeness too, for he smiled and touched her hair, but her father, irritated, told the child sharply to hold her tongue or he would send her supperless to bed.

"Here, dry yourself by the fire," he said abruptly, kicking the dogs out of the way, "and you, Joanna, warn your mother the steward has crossed the valley from Tywardreath and has a message from his mistress, if she cares to receive him." He took the remaining otter's paw from his surcoat and dangled it in front of Sybell. "Shall we give it to Isolda, or will you wear it to keep you warm?" he teased. "It will soon dry, furry and soft, inside your kirtle, the nearest thing to a man's hand on a cold night."

She shrieked in affectation and backed away, while he pursued her, laughing, and I saw by the expression in Roger's eyes that he had fully grasped the relationship between guardian and ward. The snow might remain upon the hills for days or weeks; there was little at the moment to tempt the master of this establishment back to Carminowe.

"My mother will see you, Roger," said Joanna, returning to the hall, and we crossed a passage-way into the room beyond. Isolda was standing by the window, watching the falling snow, while a small red squirrel, a bell around its neck, squatted upon its haunches at her feet, pawing at her gown. As we entered she turned and stared, and although to my prejudiced eyes she looked as beautiful as ever I realised, shocked, that she had become much thinner, paler, and there was a white streak in the front of her golden hair.

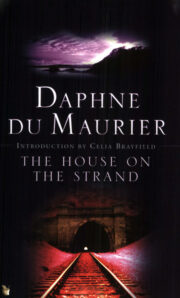

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.