"Look, I think you'll have to take me into Saint Austell," I said. "My right hand has still got this infernal cramp."

The warm sympathy which would have been hers a week ago was lacking. "I'll drive you, of course," she replied, "but it's rather odd, isn't it, suddenly to have cramp? You've never had it before. You had better keep your hand in your pocket, or the Coroner will think you have been drinking."

It was not a remark calculated to put me at my ease, and the very business of having to sit as passenger, humped beside Vita as she drove instead of being at the wheel myself, did something to my self-respect. I felt inadequate, frustrated, and began to lose the thread of the answers to the Coroner which I had so carefully rehearsed.

When we arrived at the White Hart and met Dench and Willis Vita, quite unnecessarily, apologised for her presence by saying, "Dick's disabled. I had to act as chauffeur," and the whole silly business was then explained. There was little time for talking, and I walked with the others to the building where the inquest was to be held, feeling a marked man, while the Coroner, doubtless a mild enough individual in private life, took on, in my eyes, the semblance of a judge of the Criminal Court, with the jury, one and all, adepts at finding a prisoner guilty. The proceedings started with the police evidence about the finding of the body. It was straightforward enough, but as I listened to the story I thought how strangely it must fall on other ears, and how suggestive of someone who had temporarily lost his reason and been bent on his own destruction. Doctor Powell was then called to give evidence. He read his statement in that clear, no-nonsense-about-it voice which suddenly reminded me of one of the younger Rugger-playing priests at Stonyhurst.

"This was the well-preserved body of a man of about forty-five years of age. When first examined at 1 p.m. on Saturday August 3rd death had occurred about fourteen hours previously. The autopsy, performed the following day, showed superficial bruises and abrasions of the knees and chest, deeper and more severe bruising of the upper arm and shoulder, and extensive laceration of the right side of the scalp. Underlying this was a depressed fracture of the right parietal region of the skull, accompanied by lacerations of the brain and bleeding from the right middle meningeal artery. The stomach was found to contain about one pint of mixed food and fluid, which on subsequent analysis contained nothing abnormal and no alcohol. Blood samples examined were also normal, and the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys were all normal and healthy. In my opinion, death was due to a cerebral haemorrhage following a severe crushing blow on the head."

I relaxed in my seat, tension momentarily lifted, wondering if John Willis did the same, or whether he had never had cause for concern. The Coroner then asked Doctor Powell if the brain injuries were consistent with what might be expected if the deceased had come into violent contact with a passing vehicle such as the wagon of a goods train.

"Yes, definitely," was the reply. "A point of some importance is that death was not instantaneous. He had strength enough to drag himself a few yards to the hut. The head blow was sufficient to cause severe concussion, but actual death from haemorrhage probably took place five to ten minutes afterwards."

"Thank you, Doctor Powell," said the Coroner, and I heard him call my name. I stood up, wondering if the fact that my right hand was in my pocket gave me too casual an appearance, or whether, in point of fact, anyone noticed it at all.

"Mr. Young," said the Coroner, "I have your statement here, and propose reading it to the jury. Stop me if there is anything you wish to correct." The statement, as read by him, made me sound callous, as if I had been more preoccupied in missing my dinner than anxious for the safety of my guest. The jury would get the impression of a loafer, spinning away the small hours with a cushion behind his head and a bottle of whisky at his elbow.

"Mr. Young," said the Coroner, when he had finished, "it did not occur to you to contact the police on the Friday night. Why?"

"I thought it unnecessary," I replied. "I kept expecting Professor Lane to turn up."

"You were not surprised at his getting off the train at Par and taking a walk instead of meeting you at Saint Austell as arranged?"

"I was surprised, yes, but it was quite in character. If he I had some objective in view he followed it through. Time and punctuality meant nothing to him on these occasions."

"And what do you think was the particular objective Professor Lane had in view on the night in question?" asked the Coroner.

"Well, he had become interested in the historical associations of the district, and the sites of manor-houses. We had planned to visit some of them during the weekend. When he did not turn up I assumed he must have decided to take a walk to some particular site which he had not told me about. Since I made my statement to the police I believe I have located the site he had in mind." I thought there might be a stir of interest amongst the jury but they remained unmoved.

"Perhaps you will tell us about it," said the Coroner.

"Yes, of course," I answered, self-confidence returning, and inwardly blessing the Parochial History. "I believe now, which I did not know at the time, that he was trying to locate the one-time manor of Strickstenton in Lanlivery parish. This manor belonged at one time to a family called Courte." I was careful not to mention the Carminowes, because of Vita, "who also used to own Treverran too. The quickest way between these houses, as the crow flies, would be to cross the valley above the present Treverran farm, and walk through the wood to Strickstenton."

The Coroner asked for an ordnance map, which he examined carefully. "I see what you mean, Mr. Young," he said. "But surely there is a passage-way under the railway which Professor Lane would have taken in preference to crossing the line itself?"

"Yes," I said, "but he had no map. He might not have known it was there."

"So he cut across the line, despite the fact that it was by then quite dark, and a goods-train was coming up the valley?"

"I don't think the darkness worried him. And obviously he didn't hear the train — he was so intent on his quest."

"So intent, Mr. Young, that he deliberately climbed through the wire and walked down the steep embankment as the train was passing?"

"I don't think he walked down the bank. He slipped and fell. Don't forget it was snowing at the time."

I saw the Coroner staring at me, and the jury too. "I beg your pardon, Mr. Young," said the Coroner, "did I hear you say it was snowing?"

I took a moment or two to recover, and I could feel the sweat breaking out on my forehead. "I'm sorry," I said. "That was misleading. The point was that Professor Lane had a particular interest in climatic conditions during the Middle Ages; his theory was that winters were much harder in those days than they are now. Before the railway cutting was built through the hillside above the Treesmill valley the ground would have sloped down continuously all the way to the bottom, and drifts would have lain there heavily, making communication between Treverran and Strickstenton virtually impossible. I believe, from a scientific rather than a historical point of view, he was thinking so much about this, and the general incline of the land about him, and how it would be affected by snowfall, that he became oblivious of everything else." The incredulous faces went on staring at me, and I saw one man nudge his companion, signifying that either I was a raving lunatic or the Professor had been.

"Thank you, Mr. Young, that is all," said the Coroner, and I sat down, pouring with sweat and a tremor shooting down my arm from elbow to wrist.

He called John Willis, who proceeded to give evidence that his late colleague had been in the best of health and spirits when he saw him before the weekend, that he was engaged in work of great importance to the country which he was not at liberty to speak about, but that naturally this work had no connection with his visit to Cornwall, which was in the nature of a private visit and in pursuance of a personal hobby, mainly historical.

"I must add", he said, "that I am in complete agreement with Mr. Young as to his theory of how Professor Lane met his death. I am not an antiquarian, nor a historian, but certainly Professor Lane held theories about the extent of snowfall in previous centuries," and he proceeded, for about three minutes, to launch into jargon so incomprehensible and above my head and the heads of everybody present that Magnus himself could not have surpassed it had he been giving an imitation, after a thundering good dinner, of the sort of stuff published in the more obscure scientific journals.

"Thank you, Mr. Willis," murmured the Coroner when he had finished. "Very interesting. I am sure we are all grateful for your information."

The evidence was concluded. The Coroner, summing up, directed that, although the circumstances were unusual, he found no reason to suppose that Professor Lane had deliberately walked on to the line as the train approached. The verdict was death by misadventure, with a rider to the effect that British Railways, Western Region, would do well to make a more thorough inspection of the wiring and danger notices along the line.

It was all over. Herbert Dench turned to me with a smile, as we left the building, and said, "Very satisfactory for all concerned. I suggest we celebrate at the White Hart. I don't mind telling you I was afraid of a very different verdict, and I think we might have had it but for your and Willis's account of Professor Lane's extraordinary preoccupation with winter conditions. I remember hearing of a similiar case in the Himalayas…" and he proceeded to tell us, as we walked to the hotel, of a scientist who for three weeks lived at some phenomenal altitude in appalling conditions to study the atmospheric effect upon certain bacteria. I did not see the connection but was glad of the respite, and when we reached our destination went straight to the bar and got quietly and very inoffensively drunk. Nobody noticed, and what is more the tremor in my hand ceased immediately. Perhaps after all it had been nerves.

"Well, we mustn't keep you from enjoying your delightful new home," the lawyer said, when we had consumed a brief but hilarious lunch. "Willis and I can walk up to the station."

As we moved towards the door of the hotel I said to Willis, "I can't thank you enough for your evidence. What Magnus would have called a remarkable performance."

"It made its impact," he admitted, "though you had me somewhat shaken. I wasn't prepared for snow. Still, it goes to prove what my boss always said: the layman will accept anything if it is put forward in an authoritative enough fashion." He blinked at me behind his spectacles and added quietly, "You did make a clean sweep of all the jam-jars, I take it? Nothing left that could do you or anyone else any damage?"

"Buried," I replied, "under the debris of years."

"Good," he said. "We don't want any more disasters." He hesitated, as if he might have been going to say something else, but the lawyer and Vita were waiting for us by the hotel entrance, and the opportunity was lost. Farewells were said, hands shaken, and we all dispersed. As we made our way to the car-park Vita remarked in wifely fashion, "I noticed your hand recovered as soon as you reached the bar. Be that as it may, I intend to drive."

"You're welcome," I said, borrowing her country's curious phraseology, and, tilting my hat over my eye as I got into the car, I prepared myself for sleep. My conscience pricked me, though. I had lied to Willis. Bottles A and B were empty, true enough, but the contents of bottle C were still intact, and lay in my suitcase in the dressing-room.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

THE EFFECTS OF conviviality in the White Hart subsided after a couple of hours, leaving me in a truculent mood and determined to be master in my own house. The inquest was over, and despite my gaffe about the snow, or perhaps because of it, Magnus's good name remained untarnished. The police were satisfied, local interest would die down, and there was nothing more I had to fear except interference from my own wife. This must be dealt with, and speedily. The boys had gone off riding and were not yet home. I went to look for Vita and found her eventually, tape-measure in hand, standing on the landing outside the boys room. "You know," she said, "that lawyer was perfectly right. You could get half a dozen small apartments into this place — more if you used the basement too. We could borrow the money from Joe." She flicked the tape-measure back into its case and smiled. "Have you any better ideas? The Professor didn't leave you the money to keep up his house, and you haven't a job, unless you cross the ocean and Joe gives you one. So… How about being realistic for a change?" I turned and walked downstairs to the music-room. I expected her to follow me, and she did. I planted myself before the fireplace, the traditional spot sacrosanct from time immemorial to the master of the house, and said, "Get this straight. This is my house, and what I do with it is my affair. I don't want suggestions from you, lawyers, friends, or anyone else. I intend to live here, and if you don't care to live here with me you must make your own arrangements."

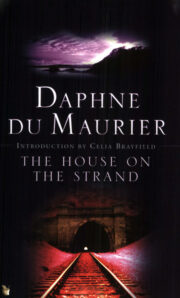

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.