I threw away my cigarette, started the car, and took the road past the church. A curious feeling of elation came to me as I swept downhill past the valley stream, and so to the low-lying, straggling shops of Par. Not ten minutes since the whole of this had been under water, the sloping Priory lands lapped by the sea. Sand-banks had bordered the wide sweep of the estuary where those bungalows stood now, and houses and shops were all blue channel with a running tide. I stopped the car by the chemists and bought some tooth-paste, the feeling of elation increasing as the girl wrapped it up. It seemed to me that she was without substance, the shop as well, and the two other people standing there, and I felt myself smiling furtively because of this, with an urge to say, You none of you exist. All this is under water.

I stood outside the shop, and it had stopped raining. The heavy pall that had been overhead all day had broken at last into a patchwork sky, squares of blue alternating with wisps of smoky cloud. Too soon to go back home. Too early to ring Magnus. One thing I had proved, if nothing else: this time there had been no telepathy between us. He might have had some intuition of my movements the preceding afternoon, but not today. The laboratory in Kilmarth was not a bogey-hole conjuring up ghosts, any more than the porch in Saint Andrew's church had been filled with phantoms. Magnus must be right in his assumption that some primary chemical process was reversible, the drug inducing this change; and conditions were such that the senses, reacting to the situation as a secondary effect, swung into action, capturing the past. I had not awakened from some nostalgic dream when the vicar tapped me on the shoulder, but had passed from one living reality to another. Could time be all-dimensional — yesterday, today, tomorrow running concurrently in ceaseless repetition? Perhaps it needed only a change of ingredient, a different enzyme, to show the future, myself a bald-headed buffer in New York with the boys grown-up and married, and Vita dead. The thought was disconcerting. I would rather concern myself with the Champernounes, the Carminowes, and Isolda. No telepathic communication here: Magnus had mentioned none of them, but the vicar had, and only after I had seen them as living persons. Then I decided what to do: I would drive to Saint Austell and see if there was some volume in the public library that would give proof of their identity.

The library was perched above the town, and I parked the car and went inside. The girl at the desk was helpful. She advised me to go upstairs to the reference library, and search for pedigrees in a book called The Visitations of Cornwall.

I took the fat volume from the shelves and settled myse]f at one of the tables. First glance in alphabetical order was disappointing. No Bodrugans and no Champernounes. No Carminowes either. And no Cardinhams. I turned to the beginning once again, and then, with quickening interest, realised that I must have muddled the pages the first time, for I came upon the Carminowes of Carminowe. I let my eye travel down the page, and there Sir John was, married to a Joanna into the bargain — he must have found the similarity of name of wife and mistress confusing. He had a great brood of children, and one of his grandsons, Miles, had inherited Boconnoc. Bococcoc… Bockenod… a change in the spelling, but this was my Sir John without a doubt.

On the succeeding page was his elder brother Sir Oliver Carminowe. By his first wife he had had several children. I glanced along the line and found Isould his second wife, daughter of one Reynold Ferrers of Bere in Devon, and below, at the bottom of the page, her daughters, Joanna and Margaret. I'd got her — not the vicar's Devon heiress, Isolda Cardinham, but a descendant.

I pushed the heavy volume aside, and found myself smiling fatuously into the face of a bespectacled man reading the Daily Telegraph, who stared at me suspiciously, then hid his face behind his paper. My lass unparalleled was no figure of the imagination, nor a telepathic process of thought between Magnus and myself. She had lived, though the dates were sketchy: it did not state when she was born or when she died. I put the book back on the shelves and walked downstairs and out of the building, the feeling of elation increased by my discovery. Carminowes, Champernounes, Bodrugans, all dead for six hundred years, yet still alive in my other world of time. I drove away from Saint Austell thinking how much I had accomplished in one afternoon, witnessing a ceremony in a Priory long since crumbled, coupled with Martinmas upon the village green. And all through some wizard's brew concocted by Magnus, leaving no side-effect or aftermath, only a sense of well-being and delight. It was as easy as falling off a cliff. I drove up Polmear hill doing a cool sixty, and it was not until I had turned down the drive to Kilmarth, put away the car and let myself into the house that I thought of the simile again. Falling off a cliff… Was this the side-effect? This sense of exhilaration, that nothing mattered? Yesterday the nausea, the vertigo, because I had broken the rules. Today, moving from one world to another without effort, I was cock-a-hoop.

I went upstairs to the library and dialled the number of Magnus's flat. He answered immediately.

"How was it?" he asked.

"What do you mean, how was it? How was what? It rained all day."

"Fine in London," he replied. "But forget the weather. How was the second trip?"

His certainty that I had made the experiment again irritated me. "What makes you think I took a second trip?"

"One always does."

"Well, you're right, as it happens. I didn't intend to, but I wanted to prove something."

"What did you want to prove?"

"That the experiment was nothing to do with any telepathic communication between us."

"I could have told you that," he said.

"Perhaps. But we had both experimented first in Blue-beard's chamber, which might have had an unconscious influence So… So, I poured the drops into your drinking-flask — forgive me for making myself at home — drove to the church, and swallowed them in the porch. His snort of delight annoyed me even more.

"What's the matter?" I asked. "Don't tell me you did the same."

"Precisely. But not in the porch, dear boy, in the churchyard after dark. The point is, what did you see?"

I told him, winding up with my encounter with the vicar, the visit to the public library, and the absence, or so I had thought, of any side-effects. He listened to my saga without interruption, as he had done the day before, and when I had concluded he told me to hang on, he was going to pour himself a drink, but he reminded me not to do likewise. The thought of his gin and tonic added fuel to my small flame of irritation.

"I think you came out of it all very well," he said, "and you seem to have met the flower of the county, which is more than I have ever done, in that time or this."

"You mean you did not have the same experience?"

"Quite the contrary. No chapter-house or village green for me. I found myself in the monks dormitory, a very different kettle of fish."

"What went on?" I asked.

"Exactly what you might suppose when a bunch of mediaeval Frenchmen got together. Use your imagination."

Now it was my turn to snort. The thought of fastidious Magnus playing peeping Tom amongst that fusty crowd brought my good humour back again.

"You know what I think?" I said. "I think we found what we deserved. I got His Grace the Bishop and the County, awaking in me all the forgotten snob appeal of Stonyhurst, and you got the sexy deviations you have denied yourself for thirty years."

"How do you know I've denied them?"

"I don't. I give you credit for good behaviour."

"Thanks for the compliment. The point is, none of this can be put down to telepathic communication between us. Agreed?"

"Agreed."

"Therefore we saw what we saw through another channel — the horseman, Roger. He was in the chapter-house and on the green with you, and in the dormitory with me. His is the brain that channels the information to us."

"Yes, but why?"

"Why? You don't think we are going to discover that in a couple of trips? You have work to do."

"That's all very well, but it's a bit of a bore having to shadow this chap, or have him shadow me, every time I may decide to make the experiment. I don't find him very sympathetic. Nor do I take to the lady of the manor."

"The lady of the manor?" He paused a moment, I supposed for reflection. "She's possibly the one I saw on my third trip. Auburn-haired, brown eyes, rather a bitch?"

"That sounds like her. Joanna Champernoune," I said. We both laughed, struck by the folly and the fascination of discussing someone who had been dead for centuries as if we had met her at some party in our own time.

"She was arguing about manor lands," he said. "I did not follow it. Incidentally, have you noticed how one gets the sense of the conversation without conscious translation from the mediaeval French they seem to be speaking? That's the link again, between his brain and ours. If we saw it before us in print, old English or Norman-French or Cornish, we shouldn't understand a word."

"You're right," I said. "It hadn't struck me. Magnus—"

"Yes?"

"I'm still a bit bothered about side-effects. What I mean is, thank God I had no nausea or vertigo today, but on the contrary a tremendous sense of elation, and I must have broken the speed-limit several times driving home."

He did not reply at once, and when he did his tone was guarded. "That's one of the things," he said, "one of the reasons we have to test the drug. It could be addictive."

"What do you mean exactly, addictive?"

"What I say. Not just the fascination of the experience itself; which we both know nobody else has tried, but the stimulation to the part of the brain affected. And I've warned you before of the possible physical dangers — being run over, that sort of thing. You must appreciate that part of the brain is shut off when you're under the influence of the drug. The functional part still controls your movements, rather as one can drive with a high percentage of alcohol in the blood and not have an accident, but the danger is always present, and there doesn't appear to be a warning system between one part of the brain and another. There may be. There may not. All this is part of what I have to find out."

"Yes," I said. "Yes, I see." I felt rather deflated. The sense of exhilaration which 1 had experienced while driving back had certainly been unusual. "I'd better lay off," I said, "give it a miss, unless the circumstances are absolutely right."

Again he paused before he answered. "That's up to you," he said. "You must judge for yourself. Any more questions? I'm dining out."

Any more questions… A dozen, twenty. But I should think of them all when he had rung off. "Yes," I said. "Did you know before you took your first trip that Roger had once lived here in this house?"

"Absolutely not," he replied. "Mother used to talk about the Bakers of the seventeenth century, and the Rashleighs who followed them. We knew nothing about their predecessors, although my father had a vague idea that the foundations went back to the fourteenth century; I don't know who told him."

"Is that why you converted the old laundry into Bluebeard's chamber?"

"No, it just seemed a suitable place, and the cloam oven is rather fun. It retains the heat if you light the fire, and I can keep liquids there at a high temperature while I'm working at something else alongside. Perfect atmosphere. Nothing sinister about it. Don't run away with the idea that this experiment is some sort of a ghost-hunt, dear boy. We're not conjuring spirits from the vasty deep."

"No, I realise that," I sald.

"To reduce it to its lowest level, if you sit in an armchair watching some old movie on television, the characters don't pop out of the screen to haunt you, although many of the actors are dead. It's not so very different from what you were up to this afternoon. Our guide Roger and his friends were living once, but are well and truly laid today."

I knew what he meant, but it was not as simple as that. The implications went deeper, and the impact too; the sensation was not so much that of witnessing their world as of taking part in it.

"I wish", I said, "we knew more about our guide. I dare-say I can dig up the others in the Saint Austell library — I've found the Carminowes already, as I told you, John, and his brother Oliver, and Oliver's wife Isolda — but a steward called Roger is rather a long shot, and is hardly likely to figure in any pedigree."

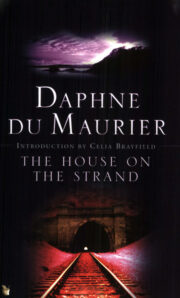

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.